Classical Mythology

The Context of Edith Hamilton's Mythology

Although her name is the only one on the cover, Edith Hamilton is not really the author of all the tales in Mythology. It is more accurate to think of her as a collector or interpreter, as she compiled the stories in the book from the writings of various Greek, Roman, and Icelandic authors. Nevertheless, Hamilton's choices reflect a personal point of view: the stories she includes, her methods of storytelling, and her omissions reveal her own interpretation of the myths and also reflect the time period in which she was writing.

Hamilton was born in 1867 to an American family living in Dresden, Germany, and grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In 1894, she graduated from Bryn Mawr, a women's school in Baltimore, and was then appointed headmistress there in 1896. In 1922, she retired from her headmistress position to focus on her writing and her studies of ancient Greek and Roman civilization. Hamilton's experiences at Bryn Mawr undoubtedly affected the perspective of Mythology, where the theme of women struggling in a male-dominated world runs throughout the text. She died in 1963, having been made an honorary citizen of Athens, an award that signified what she considered the pinnacle of her life.

Hamilton wrote a number of well-known books about Greek and Roman life, most notably The Greek Way (1930) and The Roman Way (1932). These books, along with Mythology, became standard interpretations of classical life and art, as Hamilton focused on the ways Greek and Roman value systems serve as the foundation for modern European and American societies. She wrote the books between World Wars I and II, and they clearly reflect the search for cultural roots that many felt was needed during that historical period. Written in a time of great upheaval—the global economic Depression and Europe's disintegration before World War II—Mythology's focus on the shared, broad, and ancient cultural heritage of America and Europe gave the book widespread appeal.

Again, Hamilton is not the original author of these myths, but their compiler from a variety of classical poets from ancient Greek and Roman civilization. Greek civilization flowered first, generating the paradigms, frameworks, and myths that the Romans later adopted. The earliest poet Hamilton uses is a Greek one—Homer, who is said to have composed the Iliad and the Odyssey around 1,000 BCE. These two works are the two oldest known Greek texts and are—with their clear and widespread influence—considered fundamental texts of Western culture and literature. Their depictions of heroism have provided models for social morals and ethics that still resonate today. Their imaginative power has achieved no less: their characters, images, and narratives have continued to fascinate generations of readers and guide multitudes of artists.

Hamilton draws from a number of other authors besides Homer: other Greeks, such as Hesiod, Pindar, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and Romans such as Ovid, Virgil, and Apollodorus. At the beginning of each chapter, Hamilton notes which authors she has used as source material for that chapter's stories. Such citations are important, as these different authors—widely separated by time and worldview—tell radically different kinds of stories. Hamilton's introduction offers a chronological overview of these original authors, reminding us that the Romans wrote roughly 1,000 years after Homer and about 500 years after the Greek tragedians. This time difference is significant, as the warring, fractious conglomeration of independent Greek city-states made for a very different society from the immense, stately Roman Empire, the largest and most stable empire the world had ever seen. Augustus's Rome was a rich, sophisticated, and decadent culture, and its literature reflects this spirit. Whereas myths were very practical for the Greek authors, defining their religion and explaining the world around them, Roman authors treated the myths as elaborate fantasies told purely for entertainment or as cultural hallmarks that were used to justify Roman world dominance as a divinely decreed manifest destiny.

These contrasting motivations of the classical poets, and the degree to which such motivations are reflected in their stories, remind us that even these Greek and Roman poets were not themselves the original creators of these myths. Each written retelling of a myth was merely a new version of an old story that had been told countless times before in Greek and Roman oral and written tradition. Yet each new telling represents a new interpretation that shifts emphases and draws connections not previously made. Therefore, whether intentionally or not, each retelling radiates a new and different meaning. The same may be said here of Hamilton and her retelling in Mythology.

Brief Historical Context

The idea of "ancient Greece" itself is problematic: for most of its history, the country was disunified, comprising frequently warring city-states, each with its own culture and history. Myths largely emerged from Athens, the most dominant of the city-states and the one that especially encouraged intellectual and artistic pursuits. It is not surprising, then, that the greatest literary legacy of ancient Greece would emerge from this dominant city.

The greatest Greek epics, the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, were written during the Greek Middle Ages (roughly 1100–700 BCE), most likely around 1000 BCE. These epics evolved from a long oral tradition that Homer supposedly transcribed, but his single authorship is disputed. Greek society transformed from its Dark Ages to the city-state society that would dominate the next several centuries. Over the course of this time, overseas trade prospered, with Athens and Sparta its principal cities. The Persian War (490–479 BCE) gave Athens its first great glory, proving itself a naval power. Athenian culture blossomed, as the great tragic poets Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides competed in the renowned Athenian drama festivals. Myth, literature, and drama flourished. This Athenian golden age is generally regarded as the period 478–431 BCE, ending the year Athens became embroiled in the Peloponnesian War with Sparta. Athens lost the war and their dominance in the region in 404 BCE

In 358 BCE, King Philip of Macedonia began a conquest that eventually brought all of Greece under his rule. After his murder in 336 BCE, his son Alexander the Great inherited and expanded the empire until his death in 323 BCE During the Hellenistic Period (323–146 BCE), Alexander's empire was divided, and Alexandria, Egypt, became the new cultural and literary center of the region.

Around 200 BCE, the emergent civilization in Rome began a process of overseas conquest and expansion. By the 140s BCE, the entire Greek empire had become a Roman province. The Romans, enamored with Greek culture and art, adopted much of it. After Caesar's murder in 44 BCE, a period of turmoil enveloped the Empire. Octavian, Caesar's grand-nephew, assumed control after his great defeat of Marc Anthony at Actium in 31 BCE He later became known as Augustus, whose reign from 31 BCE–A.D. 14 was a time of great prosperity and expansion for Rome. Virgil and Ovid, the most famous Roman literary figures, wrote during this period.

Overview

Mythology offers a detailed overview of the myths of ancient Greece and Rome and a brief overview of Norse mythology. Since a tradition as immense as classical mythology cannot be presented in any linear fashion, Mythology frequently contains references to characters or stories that are not explained until later. Nonetheless, it is perfectly acceptable to skip around in the book to alleviate this confusion whenever it arises.

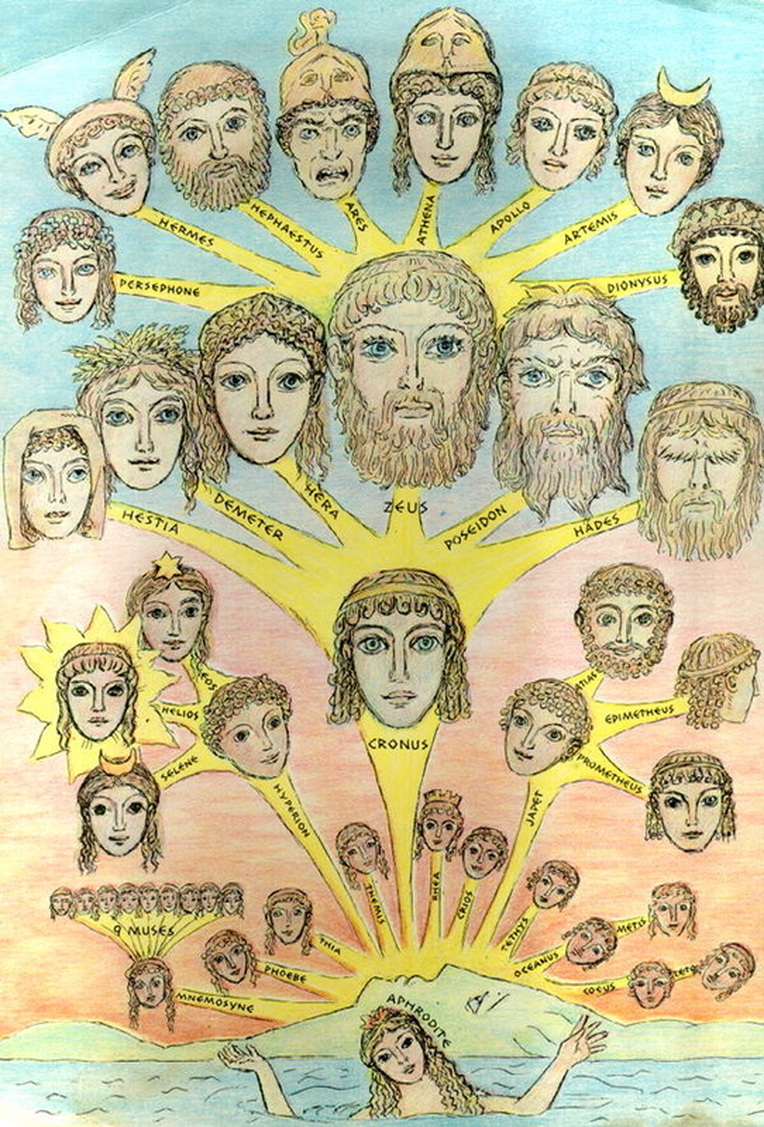

Hamilton begins by providing her rationale for the study of mythology and her understanding of its nature. She then introduces the major gods and describes the creation of the universe. Twelve primary gods live together on Mount Olympus: Zeus, the chief of these Olympians, is joined by his wife (and sister) Hera; his daughter Athena; his sons Hermes and Ares; the brother-and-sister pair Apollo and Artemis (also Zeus's children); Zeus's brothers Poseidon and Hades; his sister Hestia; and Hephaestus and his wife Aphrodite (both sometimes considered to be Zeus's children as well). The names of these gods are Greek in origin, but the Romans renamed most of the gods when they adopted them. Except in cases when a story is told exclusively by a Roman author, Hamilton employs the original Greek names in her retelling. Besides these twelve are two other important gods: Zeus's sister—Demeter and his son Dionysus—who live on earth rather than on Mount Olympus.

According to classical mythology, the universe began in a manner that—remarkably—resembles the modern scientific theory of the big bang. There was originally only chaos and darkness. Out of the swirling energy Earth and Heaven arose and gave birth to many children. Though most of these children were monsters, they eventually gave rise to the Titans, a race of gods in human form. One of the Titans overthrew his sky-father, only to see his own son Zeus overthrow him later.

Zeus and his siblings defeated all the Titans in a fierce battle and installed themselves as the lords of the universe. They created humankind and promptly began manipulating their new creatures. Zeus, an incurable philanderer, frequently descended to Earth, often in some magical form, to have his way with beautiful human women. The offspring of these liaisons grew to be the first heroes among humankind, and, with the gods' aid, won many victories against vicious monsters and completed monumental tasks. Many of these half-divine heroes, along with their few all-mortal peers, went on to found the dynasties of Greece. The most notable of these heroes are Theseus, Hercules, Cadmus, Achilles, and Aeneas.

The stories about these heroes, which account for the founding of certain cities or the legitimacy of certain dynastic bloodlines, were meant to explain phenomena that the Greeks observed in the world around them. The Greeks also told many other tales, often of a nonheroic nature, to explain the qualities of flowers, lightning, landscapes, and so on. Indeed, as Hamilton writes, these myths can be seen as "early science." Much of classical myth, however, is far more complex than these simple explanatory tales. The works of the Greek playwrights, written around 500 BCE, portray a rich, complex social and ethical fabric and are sensitive to the most profound issues of the human condition. The protagonists of these plays, caught in webs of circumstances beyond their control, have to nonetheless face their situations and make moral decisions of direst consequence to themselves and others. Many scholars consider these Greek tragedies to be as sophisticated in their psychology and writing as anything penned since.

Hamilton reserves a final section for the traditions of the Norsemen. Unlike the Greek and Roman stories, which have been retold in many versions that still exist today, the Norse tales have barely survived. Christian obsession with the destruction of pagan material swept clean Scandinavia, Germany, and other Norse areas. Only in Iceland did written versions of Norse tales survive. These Icelandic texts, which date from about A.D. 1300 but reflect a much older oral tradition, depict a bleak, dismal, and ultimately doomed universe, headed for a day of battle between good and evil in which even the gods will be destroyed. Though Hamilton's treatment of Norse myth is brief, it does offer a striking contrast to the comparatively sunny world of Mediterranean myth.