The Scramble for Africa

First Incursions: Europeans in Africa

Why? All about Europe

How? All about Tech

The Mad Rush

The Berlin Conference

The End Result

Sources

It was a manifestation of the economic, social, and military conditions that prevailed across Europe at that time.

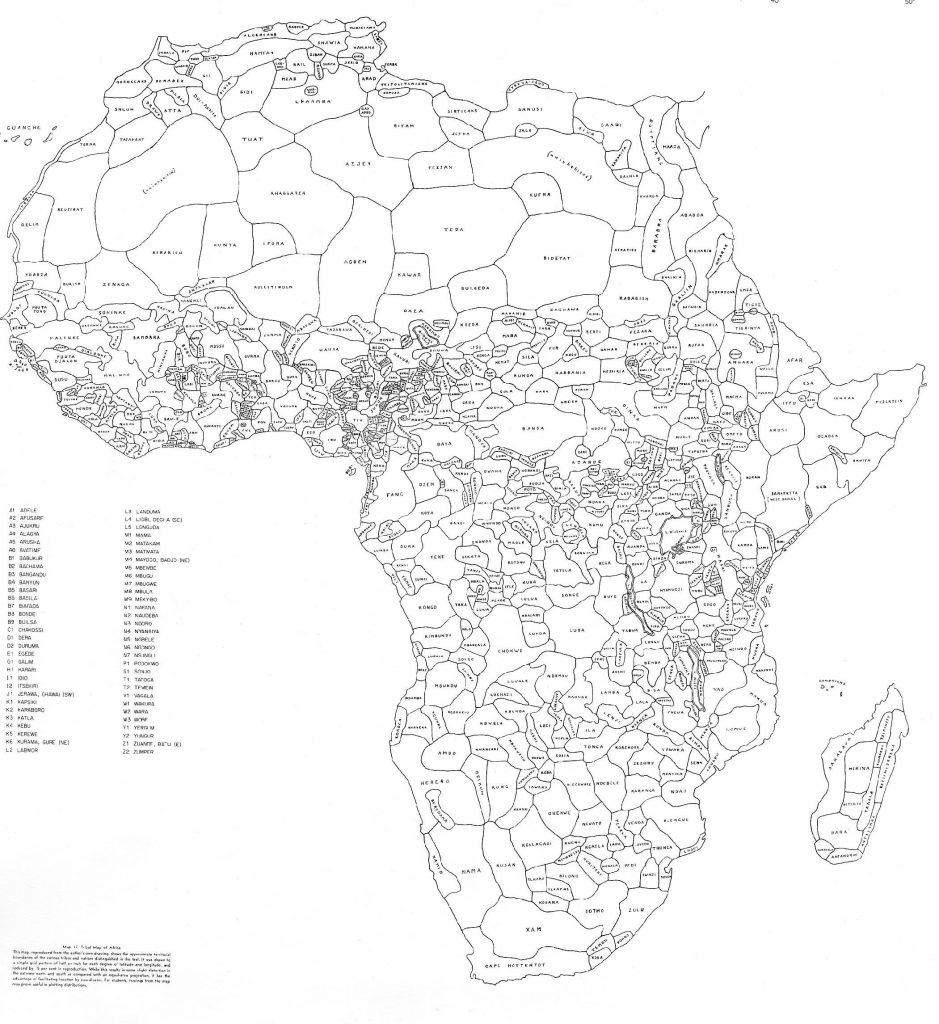

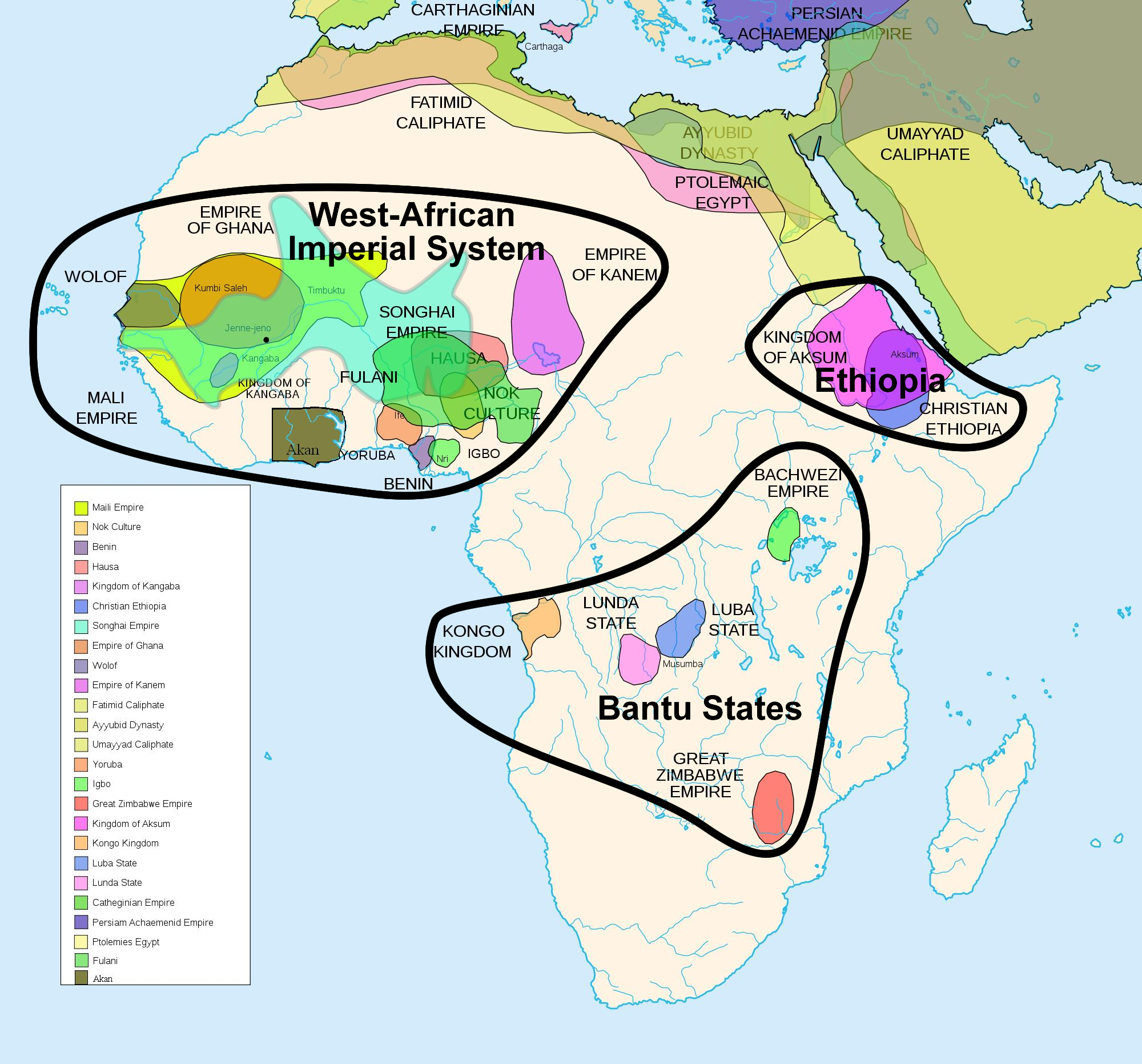

Prelude: Africa before colonization

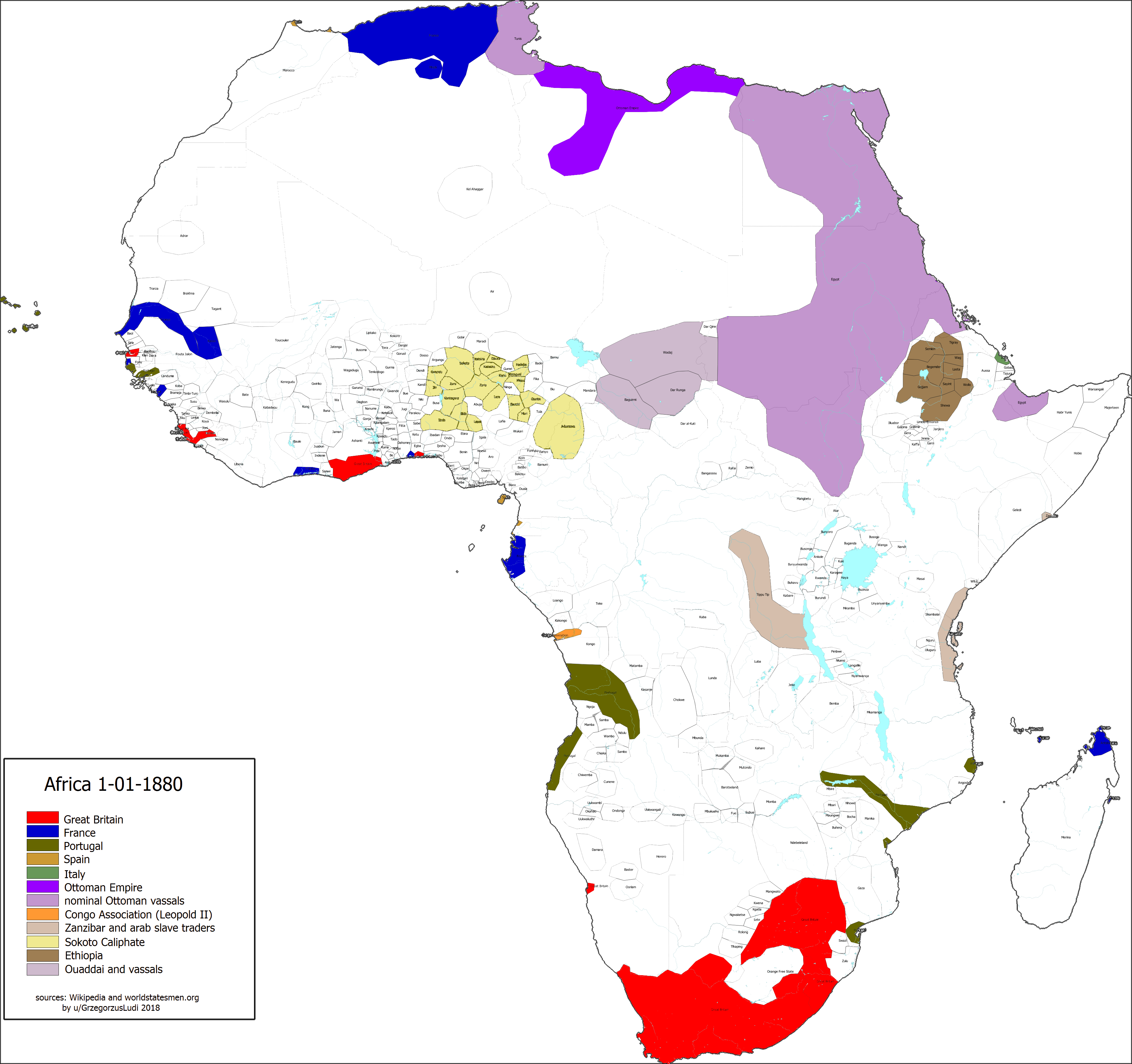

Before the Scramble — Europeans in Africa up to the 1880s

Britain had Freetown in Sierra Leone, forts along the coast of The Gambia, a presence at Lagos, the Gold Coast protectorate, and a fairly major set of colonies in Southern Africa (Cape Colony, Natal, and the Transvaal, which it had annexed in 1877).

Southern Africa also had the independent Boer Oranje-Vrystaat (Orange Free State), which existed as a tributary state to Britain until it was made a colony of the British Empire after its defeat in the Second Boer War in 1902.

France had settlements at Dakar and St Louis in Senegal, and had penetrated a inland up the Senegal river. It also had the Assinie and Grand Bassam regions of Cote d'Ivoire, a protectorate over the coastal region of Dahomey (now Benin), and had begun colonization of Algeria as early as 1830.

Portugal had well-established bases in Angola (first arriving in 1482, and subsequently retaking the port of Luanda from the Dutch in 1648) and Mozambique (first arriving in 1498 and creating trading posts by 1505).

Spain had small enclaves in northwest Africa at Ceuta and Melilla (África Septentrional Española, or Spanish North Africa).

The Ottoman Turks controlled Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia (the strength of Ottoman rule varied greatly).

Why?

- End of the Slave Trade — Britain had had some success in halting the slave trade around the shores of Africa. But Muslim traders from north of the Sahara and on the East Coast still carried on the slave trade inland, and many local chiefs were reluctant to give up the use of slaves. Reports of slaving trips and markets were brought back to Europe by various explorers, such as Livingstone, and abolitionists in Britain and Europe were calling for more to be done to eliminate slavery on the continent.

- Exploration — The African Association, or, more correctly, The Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa, was founded in London in 1788. This British club was dedicated to exploring West Africa, with the hope of discovering the headwaters and course of the Niger River and the location of Timbuktu, the "lost city" of gold. The formation of this group was effectively the beginning of the age of African exploration by the European powers. The findings of the Association's recruits accomplished much for European knowledge of Africa and its people. Their writings showed that Africans were human beings with their own cultures and commerce (and not monstrous creatures), with whom constructive relations would be possible. This "humanizing" of the African people in the minds of Europeans contributed to the European commitment to abolish slavery in Africa. As the 19th century progressed, the goals of the European explorers changed from traveling out of curiosity to seeking opportunities for commerce.

- Leopold II and Henry Morton Stanley — It may be odd to single out just one ruler, Leopld II of Belgium, and one explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, collaborated to bring about the colonization of an entire continent, but while there were many famous and influential explorers of Africa, this naturalized American (born in Wales) is the one most closely connected to the start of the Scramble for Africa. Stanley had crossed the continent and located the "missing" Livingstone, but he is more infamously known for his explorations on behalf of King Leopold II of Belgium. Stanley led an expedition to explore the Congo River in 1874–77 and reported that there was great wealth to be taken from there. Upn receiving this report, Leopold formed a committee to open up the African interior to European trade along the Congo River. Stanley worked for that committee from 1879 to 1882, establishing trading "stations" on the upper Congo. Because Belgium was not in a financial position to fund a colony at the time, Leopold established the Congo Free State by seizing the area as his personal possession. Rather than control the Congo as a colony, Leopold privately owned the region, calling it the Congo Free State — an ironic term if ever there was one. The people of the Congo were forced to labor for valued resources, including rubber and ivory, to personally enrich Leopold. Estimates vary, but about half the Congolese population died from punishment and malnutrition. Many more suffered from disease and torture. Among those who weren't killed, many were punished by having a hand and/or foot amputated. An example of this military. So Stanley's work, coupled with Leopold's creation of a vast personal fortune, triggered a rush of other European explorers who sought to do the same for various European countries.

- Capitalism — While European capitalists may have removed themselves from the African slave trade, they still wanted to exploit the natural respources of the continent (and that includes its people). New forms of "legitimate" trade were encouraged. Throughout the 19th century, explorers located vast reserves of raw materials, created trade routes, mapped rivers, and identified population centers which could be a market for manufactured goods from Europe. The usual move was the construction of plantations and the growth of cash crops, which used the region's workforce to produce rubber, coffee, sugar, palm oil, timber, etc., all for Europe. These ventures could only become more profitable if a colony could be set up which gave the European nation a monopoly on the people and the land.

- Politics — After the creation of a unified Germany (1871) and Italy (a longer process, but its capital relocated to Rome also in 1871) there was no room left in Europe for expansion. Britain, France and Germany were in an intricate political dance, trying to maintain their dominance, and the creation of an empire would secure it. France, which had lost two provinces to Germany in 1870, looked to Africa to gain more territory. Britain looked towards Egypt and the control of the Suez canal, as well as pursuing territory in gold rich southern Africa. Germany, under the expert management of Chancellor Bismarck, had come late to the idea of overseas colonies, but was now fully convinced of their worth. But no one wanted all-out warfare, or even a proxy war, over this land grab.

It's All About the Tech

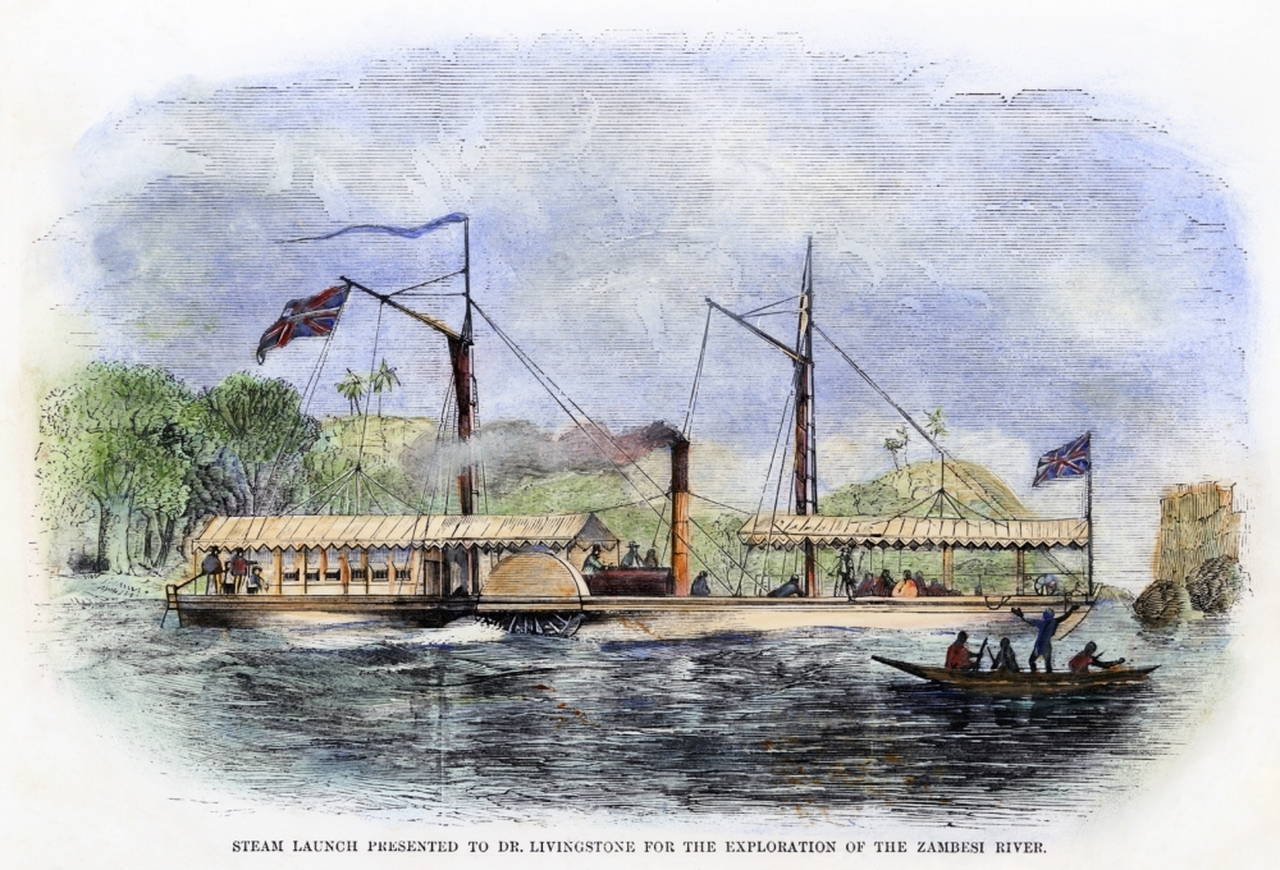

- Steam Engines and Iron-Hulled Boats — In 1840 the Nemesis arrived at Macao, south China. It changed the face of international relations between Europe and the rest of the world. The Nemesis had a shallow draft (five feet), a hull of iron, and two powerful steam engines. It could navigate the non-tidal sections of rivers, allowing access inland, and it was heavily armed. Livingstone used a steamer to travel up the Zambezi River in 1858, and had the parts transported overland to Lake Nyassa. Steamers also allowed Henry Morton Stanley and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza to explore the Congo.

- Medical Advances — So many Europeans died on the coast of West Africa by the early 19th century that it was called the "white man's grave." Europeans believed they were racially incapable of surviving in the African climate, whereas Africans were genetically equipped to do so. The cause of all those deaths wasn't climate, but disease. Europeans didn't have immunity to diseases like yellow fever and malaria in particular, but many Africans acquire such an immunity in childhood. During the 18th century only one in ten Europeans sent to the continent survived. Six of the ten would have died in their first year. But in 1817 two French scientists extracted quinine from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, which proved to be the solution to malaria. Europeans could then survive the ravages of the disease in Africa. (Yellow fever, however, continued to be a problem; as of 2022 there was still no specific treatment for the disease.)

- Military Innovation — At the beginning of the 19th century Europe was only marginally ahead of Africa in terms of available weapons. For decades traders had supplied weaponry and munitions to local chiefs, and many had stockpiles of guns and gunpowder. But in the late 1860s percussion caps were being incorporated into cartridges in Europe, so what previously existed as a separate projectile, powder, and wadding was now a single entity that was easily transported, relatively weatherproof and far more consistent. This was coupled with a second innovation, the breechloader rifle.. With this weapon, the user loads the ammunition (cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel. , as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front (muzzle). Older model muskets, held by most Africans, were muzzleloaders, which loads ammunition from the front of the barrel. These muzzleloders were slow in use (a well-trained soldier could fire a maximum of three rounds per minute) and had to be loaded while standing. Breechloaders had between two to four times the rate of fire, and could be loaded even in a prone position. Europeans, with an eye to colonization and conquest, restricted the sale of the new weaponry to Africa, maintaining military superiority.

The Mad Rush: The Early '80s

- In 1880 the region north of the Congo river became a French protectorate.

- In 1881 Tunisia became a French protectorate and the Transvaal regained its independence.

- In 1882 Britain occupied Egypt (France pulled out of joint occupation), Italy began its colonization of Eritrea.

- In 1884 British and French Somaliland was created.

- In 1884 German South West Africa, Cameroon, German East Africa, and Togo were created, and Río de Oro was claimed by Spain.

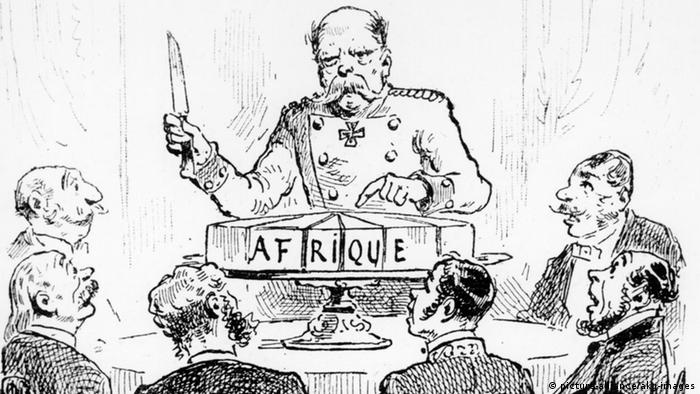

The Berlin Conference

All of this colonial activity brought the European powers close to the brink of war. But, like the Spanish and Portuguese did with another continent almost 400 years earlier, the European powers set up rules for dividing the continent they wished to colonize.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 set out the ground rules for the European powers to follow as they partitioned Africa:

- The Niger and Congo rivers were international territory; navigation on them was free to all colonial powers.

- In order to claim a "protectorate" over a region — and therefore be free to exploit both its human and natural resources — a European colonizer had to show effective occupancy of that region.

- Each colonial power had to "civilize" their protectorates, bringing both Christianity and trade to the regions over which they claimed possession.

- Each colonial power had to establish and maintain a military, religious, and administrative presence not only on the African coast, but within the interior as well.

- If all of the above conditions were satisfied, then a colonial power could claim a "sphere of influence," which would be recognized and respected by all the other European colonial powers.

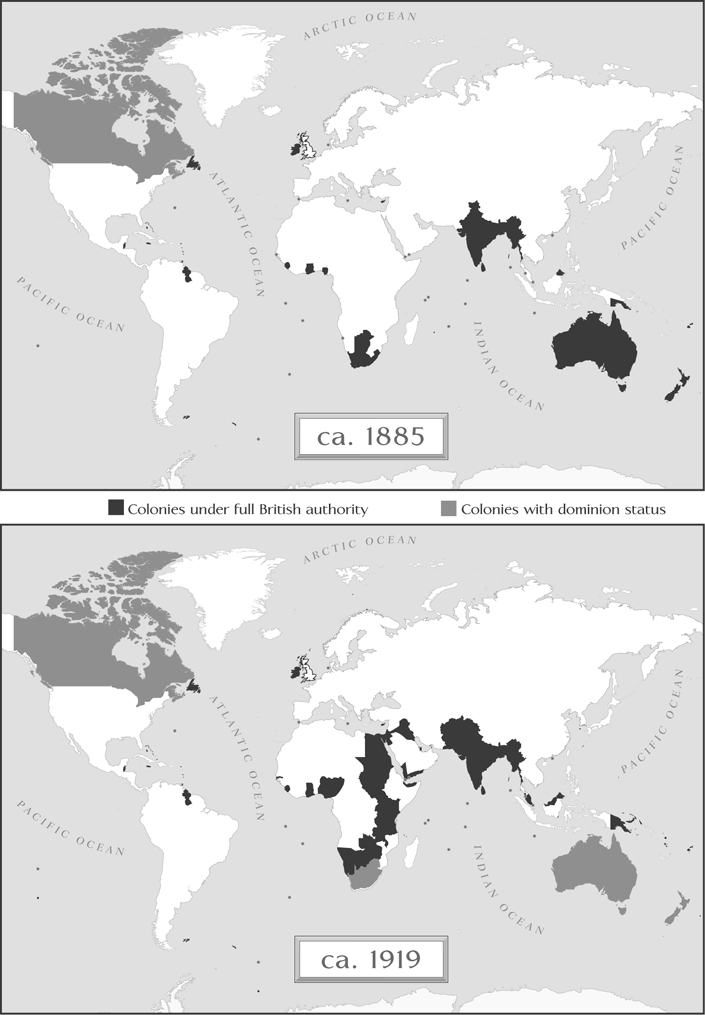

Before Berlin, imperial activity consisted of securing trade with African empires, endorsing private companies to act as quasi-state actors, and establishing infrastructure for economic expansion inland. After the Berlin Conference, imperial powers began extracting resources under the guise of private enterprise and establishing colonies.

The floodgates of European colonization had opened. By the end of this colonial frenzy, only Liberia (a colony run by ex-African-American slaves) and Ethiopia remained free of European control.

The End Result

"The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885." Africa's Great Civilizations, PBS Learning Media, gpb.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/6031c3a2-ada9-42b4-8045-52006e2a2b07/the-berlin-conference-of-1884-1885/.

Curtin, Philip D. "The White Man's Grave: Image and Reality, I780-1850." Journal of British Studies, vol. I, 1961, pp. 94-IIO.

Curtin, Philip D. The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850. U of Wisconsin P, 1964, pp. 58-87, 483-487.

Curtin, Philip D. Death by Migration: Europe's Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge UP, 1989.

Curtin, Philip D. "The End of the 'White Man's Grave'? Nineteenth-Century Mortality in West Africa." The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 21, no. 1, Summer, 1990, pp. 63-88.

"Imperialism and Colonisation: The Scramble for Africa." History For Civil Servises Examination, Self Study History, 29 December 2014, selfstudyhistory.blogspot.com/2014/12/world-historyimperialism-and_29.html.

"The Sphere of Influence Theory in Colonial Africa." World History, 26 April 2018, worldhistory.us/african-history/the-sphere-of-influence-theory-in-colonial-africa.php.