Course Information

ENGL 5526(G) A 20th & 21st Century British Lit

CRNs: UG: 86487 G: 86488

Fall 2022

TR 12:30 - 1:45

Education 1131

The University Catalog descibes this course as "a study of major British and Commonwealth poets, novelists, and dramatists against the background of the major social and cultural changes of the 20th and 21st centuries. Prerequisite(s): ENGL 2100, ENGL 2111, or ENGL 2112; or permission of the department chair. Cross Listing(s): ENGL 5526G."

What we'll be doing this semester is taking a detailed look at the major movements of Modernist, Post-Modern, and Contemporary British literature. Our definition of "British" will be pretty broad, because we'll also consider material from areas that were under British colonial rule.

We'll situate ourselves with three authors who were what we would now call "influencers," then we'll look at a few works from the Irish Literary Renaissance, because Ireland is England's closest and longest-held colony (and the Brits like to take credit for all the Nobel Prizes that Irish writers have won). After some work from WWI, we'll be set up to address Modernism as the most important literary movement of the past 200 years. I'll argue that Modernism sprang to life fully formed with Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and reached its high point with his "The Waste Land."

Following in Eliot's footsteps are the second-generation Modernists, whose experience of WWII was bad, but nowhere near as earth-shattering as WWI was for the first Modernists. Then we'll look at the real flowering of postcolonial literature, and the overlap between the idea of "British" and the notion of "Anglophone." We'll conclude with a short but shocking Indian novel that caused a sensation when it won the Booker Prize, which is considered to be "the leading literary award in the English speaking world."

- August 10: Classes begin

- August 10-15: Drop-Add period

- October 6: Last day to drop with a "W"

- November 21-26: Thanksgiving Holidays

- November 30: Last day of classes

- December 6: 12:30 pm - Final Exam

Learning Outcomes are the knowledge or skills you should gain (and be able to demonstrate) by the end of a particular course.

Career Readiness Competencies are core competencies developed by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). They address eight areas where employers agree that your abilities and skills signify your readiness to begin and/or extend your career. Below are the skills you'll have the opportunity to practice in this course.

Upon successful completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Recognize and analyze the literary elements in 20th- or 21st-century British texts.

- Situate and interpret those texts in their historical, cultural, and literary contexts.

- Create a well-developed and organized essay with clear and precise prose, presenting a sustained argument about 20th- or 21st-century British texts.

| Self-Development |

|

| Communication |

|

| Critical Thinking |

|

| Equity and Inclusion |

|

| Leadership |

|

| Professionalism |

|

| Teamwork |

|

| Technology |

|

These career readiness skills will serve you well no matter what your next steps after graduation might be. Find out more about them on this page of the NACE site.

Course Texts

You'll need to purchase these required books for this class:

The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 10th edition, volume F. Packaged with Modern and Contemporary Irish Drama, Norton Critical Edition. WW Norton, 2018. 9780393429480.

Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. Random House, 2008. 9780812979657.

I'll also be providing some resources for you, small collections from various authors that will be available on the course site in Folio.

Trigger Warning

A “trigger” is anything that might cause a person to experience a strong emotional and/or psychological response. Some triggers are shared by large numbers of people (for example, rape), while others are more idiosyncratic (for example, orange juice).

All texts read in this course, all class discussions, and all ancillary materials may contain instances of the following potential triggers, as well as other unanticipated and so unlisted potential triggers: ignorance; willful ignorance; cultural insensitivity; oppression; persecution; swearing, abuse (physical, mental, emotional, verbal, sexual), self-injurious behavior (self-harm, eating disorders, etc.), talk of drug use (legal, illegal, or psychiatric), suicide, descriptions or pictures of medical procedures, descriptions or pictures of violence or warfare (including instruments of violence), corpses, skulls, or skeletons; needles; racism; classism; sexism; heterosexism; cissexism, ableism; hatred of differing cultures or ethnicities; hatred of differing sexualities or genders; body image shaming; neuroatypical shaming; dismissal of lived oppressions, marginalization, illness, or differences; kidnapping (forceful deprivation of or disregard for personal autonomy; discussions of sex (even consensual); death or dying; beings in the natural world against which individuals may be phobic; pregnancy and childbirth; blood; serious injury; scarification; glorification of hate groups; elements which might inspire intrusive thoughts in those with psychological conditions such as PTSD, OCD, or clinical depression.

Unless expressly stated otherwise, the views, findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the texts read in this course, the classroom discussions, and the ancillary material do not necessarily represent the views of the University or the course instructor.

All texts read in this course, all class discussions, and all ancillary materials may also contain instances of overwhelming beauty, profound truths, and serious reflection on what it means to be human.

By remaining registered in this class, you agree to be exposed to all of the above. As Jenny Jarvie has written,

Structuring public life around the most fragile personal sensitivities will only restrict all of our horizons. Engaging with ideas involves risk, and slapping warnings on them only undermines the principle of intellectual exploration. We cannot anticipate every potential trigger—the world, like the Internet, is too large and unwieldy. But even if we could, why would we want to? Bending the world to accommodate our personal frailties does not help us overcome them.

— Jarvie, Jenny. “Trigger Happy.” The New Republic, 3 March 2014.

In short, texts and/or discussions in this class may make you uncomfortable. . . for many of them, that may be the whole point.

Course Structure

General

This course is a fast-paced introduction to some of the most important works written in English in the 20th and 21st centuries. So we'll be looking at:

- the effects of historical events, cultural values, and social movements on literary production;

- the pendulum swings of literary periods;

- the essential primary texts you need to know in order to understand the past 120 years; and

- the secondary sources and research that allow for a deeper understanding of these works.

Apparatus and Application

Most of the interpretations of these works I'll be offering will be pretty middle-of-the-road. They'll be informed by a close reading of the text and the application of a number of critical lenses. Since one of the learning outcoms of this course is to understand these texts in their historical, social, and cultural situations, my thoughts on them will be informed by context-oriented approaches, but our main approach will be text-oriented. We may avail ourselves of some author-oriented analyses, but we will rarely deal with reader-oriented approaches.

You'll demonstrate your analytic skill and ability to parse these texts through two exams, a short researched paper, and a more lengthy digital humanities assignment. In the paper, especially, I'll ask you to apply parts of the apparatus above to the texts we're covering.

Readings

As you will see in the schedule below, there are a variety of genres represented in this class, but there's quite a bit of poetry, more than some of you may be comfortable with. I've set up the class this way for two reasons; the first is philosophical and the second is practical. Primarily, I think the best way to capture the zeitgeist of a particular historical moment, or to understand the impact of a literary movement, is through poetry. Works in this genre contain far more distilled language than those in any other genre, so it's easier to get at the essence of the subject at hand. Also, studying poetry allows us to cover far more ground. We could spend the semester reading only novels, but the nature of the academic calendar means that we would deal with far fewer texts, and you'd be familiar with far fewer authors.

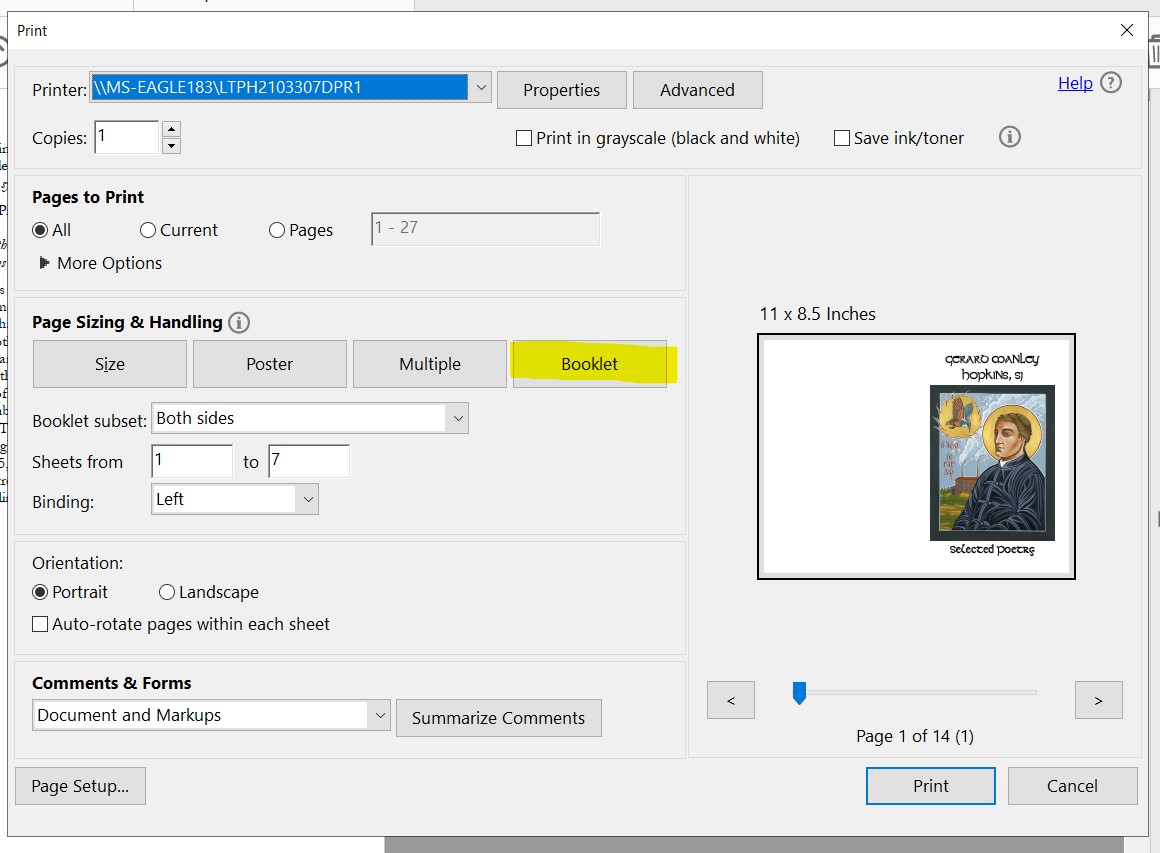

At a practical level, most of the material I'll give you is formatted to print as a small book. If you have access to a printer that will print double-sided and do a book fold, you'll see these as I intended them. If you don't have access to such a printer, then I'll also have versions available that will print single-sided on letter-sized paper. The Word versions of these files in Folio are already set to print as a book. The pdf versions in Folio can be printed single-sided on 8.5" x 11" paper (the Acrobat default), or they can be printed as a book. (The image below is the print dialog in Acrobat. Select "Booklet" - highlighted in yellow here - and make sure all the other functions match those in the screenshot.)

Whatever you do, don't open the Word doc versions of these files in Folio. Due to D2L's inability to actually render common fonts, almost everything in them will be formatted incorrectly. If you absolutely must open these files within Folio (instead of downloading and printing them), please use the pdf versions.

Paper

You'll write one short researched paper for this class. You'll submit it via a dropbox in Folio, where it will go through TurnItIn to check for academic integrity. My comments on your papers will be available to you through the Grademark view in the TurnItIn section (click on your TurnItIn score to access this).

Exams

We'll have two exams, one halfway through the course and one at the end of the course. These will contain some practical questions (can you scan a line of poetry?), some short answer questions (can you see the elements of a literary movement in a work?), and some essay questions (can you apply some of the fundamental concepts we're using to a particular piece?).

.Course Expectations

The "Carnegie Unit" is how universities define credit hours and categorize the amount of work students do for each credit hour. Each credit requires 15 "contact hours," which are essentially the hours you spend in class during the semester. And each contact hour requires two hours of outside work, or time devoted to the class that doesn't happen in the classroom itself. This is a three-credit course, with 45 contact hours. Those 45 contact hours necessitate at least 90 hours of out-of-class work on your part. That's at least 135 hours committed for each three-credit class that you take.

If you're not a self-starter, or you have problems with deadlines, or you just don't think you can commit to this level of work, you should probably look for another section of this class.

I expect that you will conduct yourself within the guidelines of the Honor System. All academic work should be completed with the high level of honesty and integrity that this University demands.

I do not tolerate academic dishonesty. Beyond the moral implications, I find it insulting. All instances of plagiarism will be reported to the Office of Student Conduct. Any instance will result in an F in the course and possibly further sanctions. Plagiarism is presenting someone else's work as your own without giving them credit. Someone else is defined as anyone other than you: another student, a friend, relative, a source on the Internet, articles or books. And work is defined as ideas as well as language. So taking someone else's ideas and putting them in your own words—or using someone else's words to express your ideas—is plagiarism. And, in the case of friends and family, it doesn't matter if they give you permission.

A note about group work: I encourage you to read and discuss these texts together outside of class. It is, in fact, the core of our endeavor, to hone our own ideas on these texts through discussions with others. You should also discuss your writing with your classmates, as hearing a number of ideas will help you create and polish your own. However, this does not mean that you should write your papers as a group. While discussion is obviously a group activity, writing is a solitary one, and should be treated as such. Any attempt to subvert this would be an instance of academic dishonesty.

The University has a more extensive definition of Academic Dishonesty (from the Student Conduct Code):

CHEATING

- submitting material that is not yours as part of your course performance;

- using information or devices that are not allowed by the faculty;

- obtaining and/or using unauthorized materials;

- fabricating information, research, and/or results;

- violating procedures prescribed to protect the integrity of an assignment, test, or other evaluation;

- collaborating with others on assignments without the faculty's consent;

- cooperating with and/or helping another student to cheat;

- demonstrating any other forms of dishonest behavior.

PLAGIARISM

- directly quoting the words of others without using quotation marks or indented format to identify them;

- using sources of information (published or unpublished) without identifying them;

- paraphrasing materials or ideas without identifying the source;

- Self-plagiarism: re-submitting work previously submitted without explicit approval from the instructor;

- unacknowledged use of materials prepared by another person or agency engaged in the selling of term papers or other academic material.

Should you wish to pursue a case of academic dishonesty through the Office of Student Conduct, I will speak at your hearing and send a copy of this syllabus along with the documents in question to the Hearing Officer, so a plea of ignorance or non-malicious intent on your part will not be valid.

Course Schedule

| DATE | CLASS ACTIVITY | DUE |

|---|---|---|

8/11 |

Introduction / Syllabus / The movement toward Modernism |

|

8/16 |

Hardy: “Hap”, “The Ruined Maid”, “Channel Firing”, “Drummer Hodge” |

|

8/18 |

Housman: “When I Was One-and-Twenty”, “To an Athlete Dying Young”, “Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff” |

|

8/23 |

Hopkins: from handout — “As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw flame”, “God’s Grandeur”, “Pied Beauty”, “The Windhover” |

|

8/25 |

Synge: The Playboy of the Western World |

|

8/30 |

Synge: The Playboy of the Western World |

|

9/1 |

Class cancelled |

|

9/6 |

Owen: “Preface”, “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, “Dulce Et Decorum Est”, “Strange Meeting”, “Disabled” |

|

9/8 |

Yeats: “The Lake Isle of Innisfree”, “When You Are Old”, “Adam’s Curse”, “Easter, 1916” |

|

9/13 |

Yeats: “The Second Coming”, “Leda and the Swan”, “Sailing to Byzantium”, “Among School Children” |

|

9/15 |

Joyce: “Araby” |

|

9/20 |

Joyce: “The Dead” |

|

9/22 |

Exam 1 |

|

9/27 |

Eliot: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” |

|

9/29 |

Eliot: “The Waste Land” |

|

10/4 |

Eliot: “The Waste Land” |

|

10/6 |

Smith: “Sunt Leones”, “Our Bog Is Dood”, “Not Waving but Drowning”, “Thoughts About the Person from Porlock” |

|

10/11 |

Auden: “Musée des Beaux Arts”, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats”, “The Unknown Citizen”, “The Shield of Achilles” |

PAPER 1 |

10/13 |

Thomas: “The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower”, “Fern Hill”, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” |

|

10/18 |

Larkin: “Church Going”, “MCMXIV”, “High Windows”, “This Be the Verse”, “Aubade” |

|

10/20 |

Walcott: “As John To Patmos”, “Ruins of a Great House”, “The Almond Trees”, “The Sea Is History” |

|

10/27 |

Heaney: poems TBA |

|

11/1 |

Heaney: poems TBA |

|

11/3 |

Boland: “Anorexic”, “The Pomegranate”, “In Which the Ancient History I Learn Is Not My Own”, “Quarantine” |

|

11/10 |

Roy, The God of Small Things |

|

11/12 |

Roy, The God of Small Things |

|

11/17 |

Roy, The God of Small Things |

|

11/19 |

Roy, The God of Small Things |

|

11/29 |

Roy, The God of Small Things |

DH ASSIGNMENT |

12/6 |

12:30 pm : EXAM 2 |

Instructor

I'm Dr. Joe Pellegrino, an Associate Professor in the Literature department. I teach lots of different classes. My specialties are Irish literature and postcolonial literature, so I end up doing classes that don't fit into the standard Brit Lit/American Lit model: Irish lit, African lit, etc. Basically, if other people in my department can teach it, I don't teach it.

It seems like I went to school forever, and went to lots of different schools: Duquesne University, St. Louis University, Mannes College of Music, The New England Conservatory, and UNC-Chapel Hill, which is where I did my last degree. I've also taught at a lot of schools: Duquesne, UNC, Eastern Kentucky University, University of South Carolina-Upstate, Greenville Tech, Converse College, and here at GS. I've got some experience in online education; I was a University Director for the (short-lived) Kentucky Commonwealth Virtual University, and have taught online classes for over 20 years now.

Professionally, I also edit two international journals, The Journal of Global Postcolonial Studies and The International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. I'm interested in a number of fields, but most of my publications are either on Irish studies, postcolonial lit, or teaching.

I have only one item on my bucket list: to see the Northern Lights. One day I'll get there, but in the meantime I'm negotiating the lives of two teen daughters, making heirloom furniture (pretty much a middle-aged guy cliché), keeping up with new technology, wishing I could spend more time doing music, and trying to keep my head above water.

- Email: jpellegrino@georgiasouthern.edu

- Phone: 912.478.5853

- Office Hours: M: 12:00-1:45 | R: 11:00-12:15, 2:00-3:15 | F: 11:00-11:50

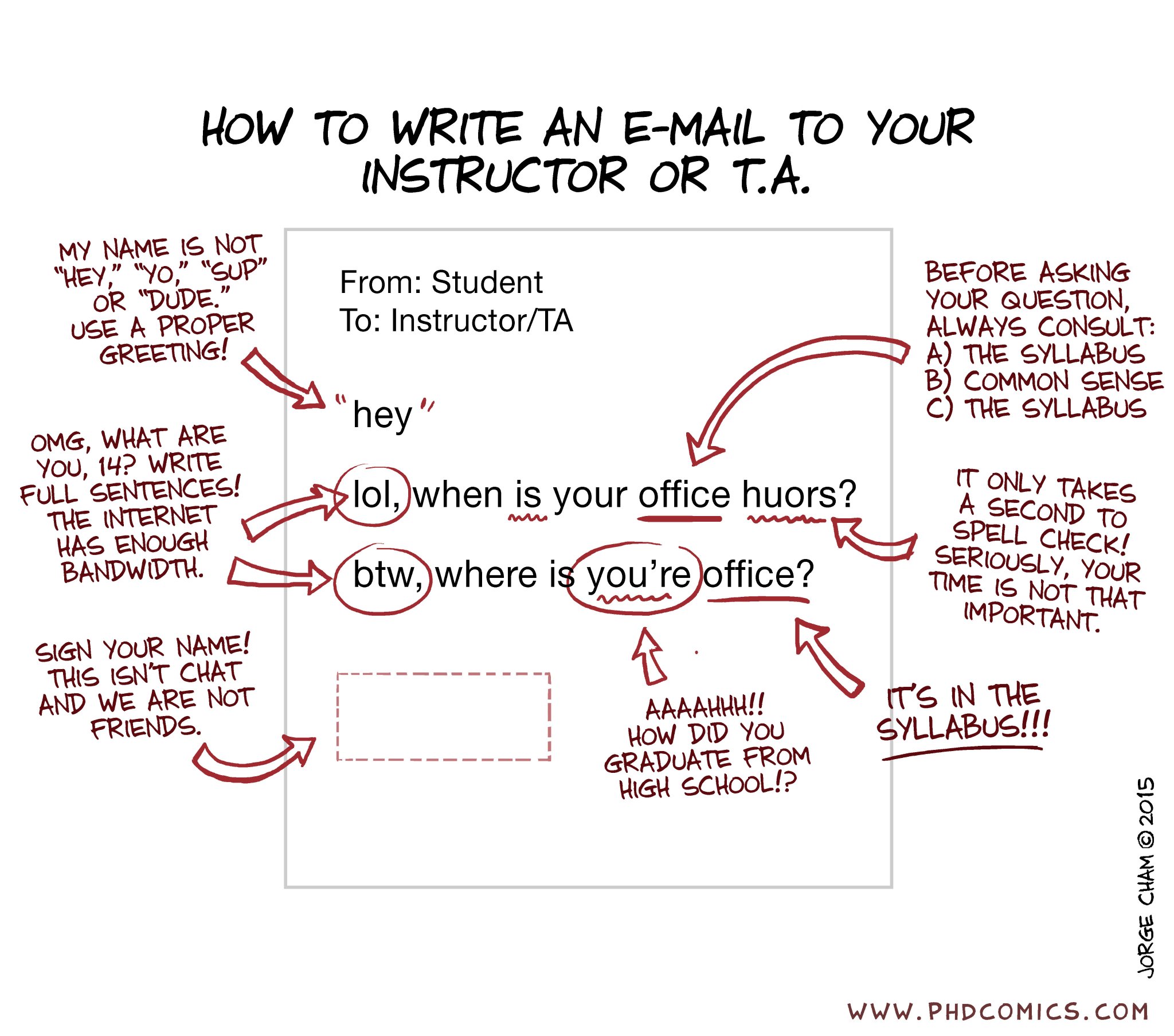

Please don't hesitate to post to me if you have a question about any of the readings, especially if you're struggling to figure them out. But please think twice about posting questions where the answer is either in this syllabus or in the course schedule. If you do, I have two options for a reply: I can copy and paste material from the syllabus or schedule just for you, but that's redundant, since you already have access to the material. Or I can reply with something like "check the syllabus" or "check the schedule," which you should already know to do. Since neither of those are satisfactory, if you ask a question that is already answered in the syllabus or in the schedule, I won't be replying at all. So if you don't hear back from me, you should know that the answer to your question is in this document (since the course schedule is here as well.)

CLASS POLICIES

If you need additional work on the surface features of your writing, I'll let you know. Basically, if I can't understand what you're trying to say in your first paper, then you'll have to work at writing more clearly. I'll ask you to schedule sessions at the Writing Center in order to be more successful on your next paper.

The reason professors make students write papers is not because we love to mark them up, or because we somehow enjoy this. I'm willing to bet that every professor you ask would say that marking and grading papers is the worst part of their job. I know it is for me. The only thing that makes it bearable is hoping that I'll be able to engage with your ideas, or see the texts we're covering through your eyes. But if I have to stop after every sentence to figure out what you're trying to say, I'm most certainly not thinking about your ideas.

So do yourself a favor: give yourself enough time to do a good job on these papers. Remember that writing clearly takes far more time than you think it does, because you have to consider your argument from a reader's perspective, not your perspective.

I realize that the grand academic dance of submitting your work, having it evaluated, then responding to that evaluation (either through improving your work in your next paper, or by coming to see me in my office) is essentially a negotiation between us. You want to demonstrate your abilities with X amount of work, an amount that you think deserves a certain grade. You submit your work without knowing how others will see it, and only become aware of their perceptions when your work is returned to you with my comments. But this puts you at a disadvantage, because you're making your first move in this negotiation blindly.

So in the spirit of openness, let me try to level the playing field by giving you a few tips:

- This is academic writing, where clarity and concision are essential. If your work isn't clear, if every sentence doesn't hang together, you're losing the negotiation. What you have written may make sense to you, but it needs to make sense to your readers as well.

- At the post-secondary level, your work isn't evaluated in terms of the amount of work you put into it. Just like any other skill, the amount of effort necessary to master academic writing varies from person to person. I am sure that it would take me far more effort than most of you to get back to playing football. But even if I did ten times the work you did, when we both showed up on the field we'd be evaluated on our skills, not on the time it took us to gain them.

- If you pay attention to what the prompt is asking you to write about, and keep that in mind as you think about your paper, you're making a good start.

- if you look at the rubric, especially the distinctions between the levels of performance in content and form, you should get a good idea of how successful your paper will be.

- If you're wondering if your "X amount of work" is enough, it isn't.

- And one last personal comment:

Before we had things like TurnItIn and other automatic checkers on academic integrity, I was the guy other faculty members went to to track down cases of suspected plagiarism. When Google was just getting off the ground, I was a beta tester for them (one of 25 in the country). I've also been teaching English for over 40 years now. So if you're thinking that you've changed enough of that material that you've copied and pasted to make it look like your own work, think again. If writing and evaluating papers is a negotiation, then presenting someone else's work as your own is a gamble, and you're betting your academic career that you can get away with it. I've just told you what I bring to the table, so if you really think you can get away with it, my only advice is to do it as early as possible, so you can spare yourself the work for the rest of semester, because you'll already be gone from this class.

You should submit your papers into the appropriate dropbox in the Learning Management System (Folio).

I DO NOT ACCEPT LATE ASSIGNMENTS. NO EXCEPTIONS, NO EXCUSES. A late assignment is any work that is not turned in by the deadline, when the dropbox closes. This means that you must anticipate any problems that will occur. In other words, a computer / printer / drive / car / arm being broken at the last minute is not an excuse. To avoid last-minute catastrophes (which always occur), DO NOT WAIT UNTIL THE LAST MINUTE TO DO YOUR WORK.

I'm a strong advocate for those who are differently abled, so of course I want to be in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). I'll honor any request for reasonable accommodations made by those with disabilities or demonstrating appropriate need for learning environment adjustments. However, I can only make those accommodations if they're accompanied by an accommodation letter from the Student Accessibility Resource Center (SARC) before academic accommodations can be implemented.

For additional information, please call the SARC office at (912) 478-1566 on the Statesboro campus, or at (912) 344-2572 on the Armstrong and Liberty campuses.

You'll write one short paper (1,000-1,500 words), using a minimum of four sources secondary sources. Two of these sources MUST be actual texts from the Henderson Library. That is, at least two of your sources cannot be electronic; you must go to the library and find them, then copy the pages that you used for this assignment and submit them with your paper. Topics will focus on works by authors covered in the class, but not on works covered in the class. Thus it would be beneficial to consider the work of poets we're looking at, unless you are committed to reading more drama, short, or long fiction. An extended prompt will be discussed and presented in class (and is now included below).

Comments on your papers and your grade on the paper will be available to you through the Grademark view in the TurnItIn section (click on your TurnItIn score to access this).

After you submit your paper and TurnItIn has completed its analysis, you are able to see your TurnItIn Originality Score. In general, lower numbers are better here, unless you're quoting a lot of material from the text. Your score will also have a color attached to it. If the color you see is anything other than green, check your paper again to see that you have cited all your sources correctly. If you have, then you're good. If you haven't, then you can revise your paper and resubmit it. I will evaluate only the most recent version of your paper in the dropbox, but you can submit as many versions of it as you feel necessary.

- Click on the colored section that has a percentage within it next to your paper title under the "TurnItIn Score" heading. This will take you to the TurnItIn suite.

- Once your paper loads, click on the icon at the top of the array of icons to the right of your paper. This will allow you to view multiple layers with your paper.

- In the list that flies out from the right, click on all three layers: Grading, Similarity, and e-rater.

- Double-click on any blue box in your paper to see my comment attached to that box.

- Double-click on any number in your paper to see the match that TurnItIn connected with the passage it highlighted.

- Double-click on any purple comment in your paper to see the machine-scored grammar corrections and access the handbook available to you.

Any paper you write about a literary work is an argument. And that argument is always the same: “You should read this work (or this section of a work) the way that I do.” That doesn’t mean that your paper needs to address the entirety of a work, only that understanding the facet of the work you choose to explore must, in the end, contribute to a richer reading of that work.

So you need to be sure that you have something specific that you want to say about the work. This specific argument that you want to make will be your thesis. You’ll support this thesis in two ways: by citing evidence and using examples from the work itself, and by appealing to the arguments made by other commentators on that work.

Possible Topics

Since the vast majority of what’s on the table for your consideration is poetry, I’ll tailor these comments to writing specifically about that genre, and move from the local and self-contained to more global possibilities.

The Contribution of Prosody

Look at the form, meter, and rhyme scheme of the poem. Does the poet play with any of those? If so, does this change address, highlight, or ironically contrast with anything else in or surrounding the poem?

Figurative Language

Is there any significant use of language that goes beyond the literal meaning of the words themselves? Do the sounds, syntax, or word order deviate from what is considered the normal patterns of use? Are there literary devices being used that affect how you read the poem?

Thematic Concerns

What is the broad central idea supporting or emerging from this work? Is there an underlying insight, moral, or idea within it? How is that theme illustrated? (Through the matter covered in the previous sections, perhaps?) Can you say something about this interplay that isn’t obvious? Can you get beyond something like “Sappho’s poetry is about love, because she says, ‘My theme is love, and love’s daimonic character’”? Chaucer’s Pardoner announces his theme blatantly: “My theme is alwey oon, and ever was— ‘Radix malorum est Cupiditas.’” What’s interesting here isn’t the trite theme of his story, but the juxtaposition of that Pardoner’s theme with his character.

Contexts

How does the poem you are looking at relate to the historical, social, or cultural contexts in which it was written? Addressing questions like these may involve research into other fields, like philosophy, history, religion, economics, music, or the visual arts.

A Slight Nod to Prose

Just in case you want to tackle some other stories or novels, here are some starting and stopping points to consider when coming up with a topic to write on.

Where to start thinking about writing about prose:

Character

Type and development: protagonist, antagonist, or foil? hero or antihero? growth throughout the text, or static?

Setting

Realistic or imaginary? How does it serve, support, or hinder the other elements?

Plot/Action

Freytag’s Pyramid: 1) Exposition; 2) Rising Action; 3) Climax; 4) Falling Action; and 5) Resolution.

Conflict

Internal or external? Human vs. human, or human vs. the world?

Point of View

How does the perspective from which the story is told influence your reading?

Mood

How does the writer’s use of language create the emotional quality of the story? How are events, settings, character reactions, and even the outcome described?

Where to end when writing about prose:

So What?

Why is knowing what you just told us worth it? What do we now know about the text that we didn’t before we read your work?

Instead of a major research paper, you'll be working on a Digital Humanities project. Each of you will be asked to annotate a number of pages from Derek Walcott's famous book-length poem, Omeros. The pages you'll receive will be highlighted with my suggestions for words, phrases, or ideas that need annotations, but there may, and probably will, be several more that you find on your own.

Annotations can vary from mere definitions of unfamiliar words to unpacking the information necessary for understanding those words. Annotation includes adding purposeful notes, key words and phrases, definitions, and connections tied to specific sections of text. Your work will support other readers’ ability to clarify and synthesize ideas, pose relevant questions, and capture analytical thinking about these texts. Details of the process and a rubric for the quantity and quality of annotations required will be available during the first two weeks of class.

Rubric

Essay Rubric

Your papers for this class will be evaluated according to this rubric:

| ENGL ESSAY RUBRIC | ||

| GRADE | CONTENT | FORM |

| A |

|

|

| B |

|

|

| C |

|

|

| D |

|

|

| F |

|

|

For each sentence in your paper, I ask the following questions:

- What are you saying?

At a basic level, I’m trying to decode the meaning of each sentence. If I cannot understand what you’re trying to say, everything that follows is problematic. If your sentence is confused, convoluted, or contradictory, you make it difficult, or even impossible, for me to answer this basic question. - Is what you’re saying accurate?

Does this sentence demonstrate that you understand the text or the critic you’re addressing? For instance, if you’re summarizing someone else’s argument, I need to assess if you’re being true to the original author's intent. In your response, I’m assessing your evidence and examples. - Is what you’re saying well-expressed grammatically and mechanically?

This assumes that your grammar and mechanics aren’t so bad that I’ve been stymied back up at Question #1. - Does the writing have appropriate flow?

Does each idea link up with the one previous to it and the one to follow in a way that meets audience needs, attitudes, and knowledge?

If I can answer all four of these questions positively for every sentence, you’re doing well. But when the answer is no, complications ensue. If I can’t understand what you’re saying, I have no way to engage with your ideas, and so I have additional questions.:

- Do you not understand the original text you’re addressing?

- Do you understand the original text, but your writing leaves a gap between that understanding and what is written on the page?

DH Rubric

Your digital humanities assignment for this class will be evaluated according to this rubric:

| DIGITAL HUMANITIES ASSIGNMENT RUBRIC | ||||

| Criterion | Max points | Performance for full credit | Points per item | Bonus possible? |

| Number of annotations | 20 | 20 + annotations | 1 point each | Y, up to 10 |

| Reference to/use of literary sources | 20 | 10 + annotations with references | 2 points each | N |

| Variety of sources | 15 | 5 + different literary sources | 3 points each | Y, up to 10 |

| Depth of annotations Annotation of a paragraph or more. |

25 | 10 + annotations | 2.5 points each | Y, up to 10 |

| Use of multimedia (image, video, audio) Each use must be cited; does not count as a literary source. |

10 | 10 + annotations incorporating media | 1 point each | Y, up to 5 |

| Grammar / Usage / Formatting | 10 | No errors | – 1 per error | N |

Evaluation

| Paper 1 | 20% |

| DH Assignment | 25% |

| Exam 1 | 20% |

| Exam 2 | 25% |

| Participation | 10% |

| TOTAL | 100% |