The 1960s

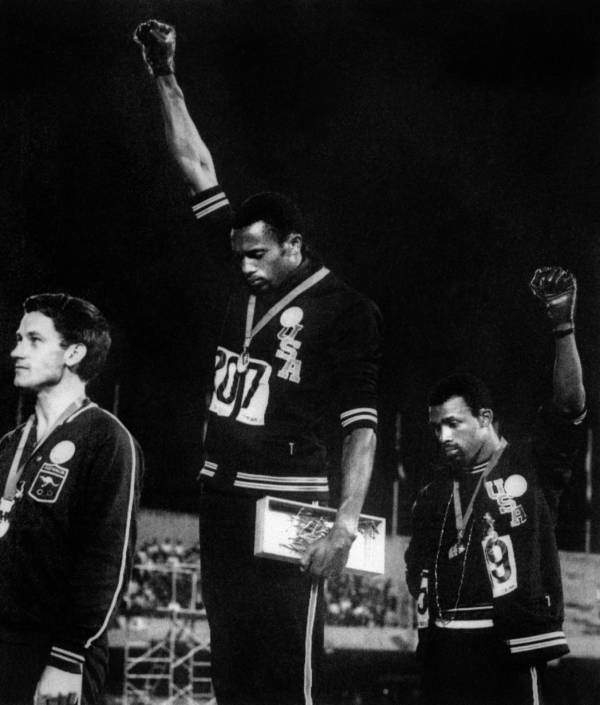

Early in the decade, African American college students, impatient with the slow pace of legal change, challenged segregation in the South. Their efforts led the federal government to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination in public facilities and employment, and the 24th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, guaranteeing voting rights.

The examples of the civil rights movement inspired other groups to press for equal rights. The women's movement fought for equal educational and employment opportunities, and brought about a transformation of traditional views about women's place in society. Mexican Americans battled for bilingual education programs in schools, unionization of farm workers, improved job opportunities, and increased political power. Native Americans pressed for control over their lands and resources, the preservation of native cultures, and tribal self-government. Gays and lesbians organized to end legal discrimination based on sexual orientation.

In a far-reaching effort to reduce poverty, alleviate malnutrition, extend medical care, provide adequate housing, and enhance the employability of the poor, President Lyndon Johnson launched his Great Society Program in 1964. But the Vietnam War, inner-city rioting, and the rise of a militant antiwar movement and the counterculture, contributed to a political backlash that would lead the Republican Party to control the presidency for 10 of the next 14 years.

The New Left and the Counterculture

The New Left had a series of heroes, ranging from Marx, Lenin, Ho [Chi Minh], and Mao to Fidel, Che, and other revolutionaries. It also had its own uniforms, rituals, and music. Faded-blue work shirts and jeans, wire-rimmed glasses, and work shoes were de rigueur even if the dirtiest work the wearer performed was taking notes in a college class. The proponents of the New Left emphasized their sympathy with the working class—an emotion that was seldom reciprocated—and listened to labor songs that once fired the hearts of unionists. The political protest folk music of Greenwich Village—of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, and their crowd—inspired the New Left.

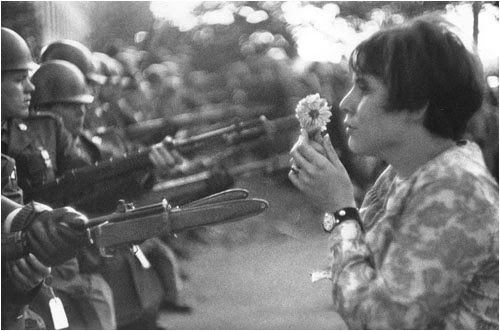

But the New Left was only one part of youth protest during the 1960s. While the New Left labored to change the world and remake American society, other youths attempted to alter themselves and reorder consciousness. Variously labeled the counterculture, hippies, or flower children, they had their own heroes, music, dress, and approach to life.

In theory, supporters of the counterculture rejected individualism, competition, and capitalism. Adopting rather unsystematic ideas from oriental religions, they sought to become one with the universe. Rejection of monogamy and the traditional nuclear family gave way to the tribal or communal ideal, where members renounced individualism and private property and shared food, work, and sex. In such a community, love was a general abstract ideal rather than a focused emotion.

The quest for oneness with the universe led many youths to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs. LSD had a particularly powerful allure. Under its influence, poets, musicians, politicians, and thousands of other Americans claimed to have tapped into an all-powerful spiritual force. Timothy Leary, the Harvard professor who became the leading prophet of LSD, asserted that the drug would unlock the universe.

Although LSD was outlawed in 1966, the drug continued to spread. Perhaps some takers discovered profound truths, but by the late 1960s, drugs had done more harm than good. The history of the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco illustrated the problems caused by drugs. In 1967, Haight was the center of the counterculture, the home of the flower children. In the "city of love," hippies ingested LSD, smoked pot, listened to "acid rock," and proclaimed the dawning of a new age. Yet the area was suffering from severe problems. High levels of racial violence, venereal disease, rape, drug overdoses, and poverty ensured more bad trips than good.

Even music, which along with drugs and sex formed the counterculture trinity, failed to alter human behavior. In 1969, journalists hailed the Woodstock music festival as a symbol of love. But a few months later, a group of Hell's Angels violently interrupted the Altamont Raceway music festival. As Mick Jagger sang "Under My Thumb," an Angel stabbed a black man to death.

Like the New Left, the counterculture fell victim to its own excesses. Sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll did not solve the problems facing the United States. And by the end of the 1960s, the counterculture had lost its force.

The Vietnam War

Vietnam was the longest war in American history and the most unpopular American war of the 20th century. It resulted in nearly 60,000 American deaths and in an estimated 2 million Vietnamese deaths. Even today, many Americans still ask whether the American effort in Vietnam was a sin, a blunder, a necessary war, or whether it was a noble cause, or an idealistic, if failed, effort to protect the South Vietnamese from totalitarian government.

Between 1945 and 1954, the Vietnamese waged an anti-colonial war against France, which received $2.6 billion in financial support from the United States. The French defeat at Dien Bien Phu was followed by a peace conference in Geneva. As a result of the conference, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam received their independence, and Vietnam was temporarily divided between an anti-Communist South and a Communist North. In 1956, South Vietnam, with American backing, refused to hold unification elections. By 1958, Communist-led guerrillas, known as the Viet Cong, had begun to battle the South Vietnamese government.

To support the South's government, the United States sent in 2,000 military advisors—a number that grew to 16,300 in 1963. The military condition deteriorated, and by 1963, South Vietnam had lost the fertile Mekong Delta to the Viet Cong. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson escalated the war, commencing air strikes on North Vietnam and committing ground forces—which numbered 536,000 in 1968. The 1968 Tet Offensive by the North Vietnamese turned many Americans against the war.

The next president, Richard Nixon, advocated Vietnamization, withdrawing American troops and giving South Vietnam greater responsibility for fighting the war. In 1970, Nixon attempted to slow the flow of North Vietnamese soldiers and supplies into South Vietnam by sending American forces to destroy Communist supply bases in Cambodia. This act violated Cambodian neutrality and provoked antiwar protests on the nation's college campuses.

From 1968 to 1973, efforts were made to end the conflict through diplomacy. In January 1973, an agreement was reached; US forces were withdrawn from Vietnam, and US prisoners of war were released. In April 1975, South Vietnam surrendered to the North, and Vietnam was reunited.

Consequences

The Vietnam War cost the United States 58,000 lives and 350,000 casualties. It also resulted in between 1,000,000 and 2,000,000 Vietnamese deaths.

The US Congress enacted the War Powers Act in 1973, requiring the president to receive explicit Congressional approval before committing American forces overseas.

Events

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Post-WWII US Culture