The 1970s

Movement on the Right:

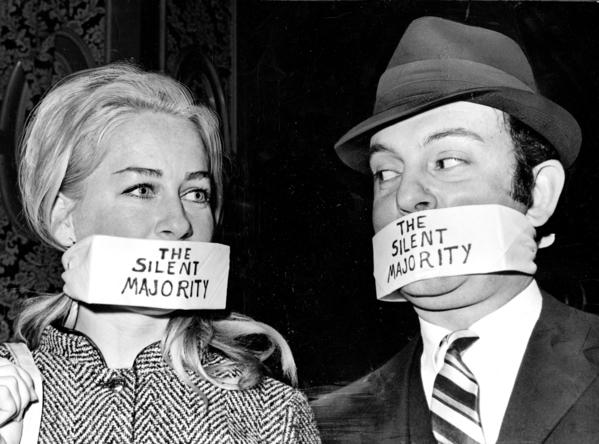

The "Silent Majority"

Many Americans, particularly working class and middle class whites, responded to the turbulence of the late 1960s—the urban riots, the antiwar protests, the alienating counterculture—by embracing a new kind of conservative populism. Sick of what they interpreted as spoiled hippies and whining protestors, tired of an interfering government that, in their view, coddled poor people and black people at taxpayer expense, these individuals formed what political strategists called a “silent majority.”

This silent majority swept President Richard Nixon into office in 1968. Almost immediately, Nixon began to dismantle the welfare state that had fostered such resentment. He abolished as many parts of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty as he could, and he made a show of his resistance to mandatory school desegregation plans such as busing. On the other hand, some of Nixon’s domestic policies seem remarkably liberal today: For instance, he proposed a Family Assistance Plan that would have guaranteed every American family an income of $1,600 a year (about $10,000 in today’s money), and he urged Congress to pass a Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan that would have guaranteed affordable health care to all Americans. In general, though, Nixon’s policies favored the interests of the middle class people who felt slighted by the Great Society of the 1960s.

As the 1970s continued, some of these people helped shape a new political movement known as the “New Right.” This movement, rooted in the suburban Sun Belt, celebrated the free market and lamented the decline of “traditional” social values and roles. New Right conservatives resented and resisted what they saw as government meddling. For example, they fought against high taxes, environmental regulations, highway speed limits, national park policies in the West (the so-called “Sagebrush Rebellion”) and affirmative action and school desegregation plans. (Their anti-taxism emerged most notably in California in 1978, when the Proposition 13 referendum— “a primal scream by The People against Big Government,” said The New York Times—tried to limit the size of government by restricting the amount of property tax that the state could collect from individual homeowners.)

Movements on the Left:

The Environmental Movement

In some ways, though, 1960s liberalism continued to flourish. For example, the Environmental Movement—the crusade to protect the environment from all sorts of assaults: toxic industrial waste in places like Love Canal, New York; dangerous meltdowns at nuclear power plants such as the one at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania; highways through city neighborhoods—really took off during the 1970s. Americans celebrated the first Earth Day in 1970, and Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act that same year. The Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act followed two years later. The oil crisis of the late 1970s drew further attention to the issue of conservation. By then, environmentalism was so mainstream that the US Forest Service’s Woodsy Owl interrupted Saturday morning cartoons to remind kids to “Give a Hoot; Don’t Pollute.”

Movements on the Left:

The Women’s Rights Movement

During the 1970s, many groups of Americans continued to fight for expanded social and political rights. In 1972, after years of campaigning by feminists, Congress approved the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution, which reads: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” It seemed that the Amendment would pass easily. Twenty-two of the necessary 38 states ratified it right away, and the remaining states seemed close behind. However, the ERA alarmed many conservative activists, who feared that it would undermine traditional gender roles. These activists mobilized against the Amendment and managed to defeat it. In 1977, Indiana became the 35th—and last—state to ratify the ERA.

Disappointments like these encouraged many women’s rights activists to turn away from politics. They began to build feminist communities and organizations of their own: art galleries and bookstores, consciousness-raising groups, daycare and women’s health collectives (such as the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, which published “Our Bodies, Ourselves” in 1973), rape crisis centers and abortion clinics.

Movements on the Left:

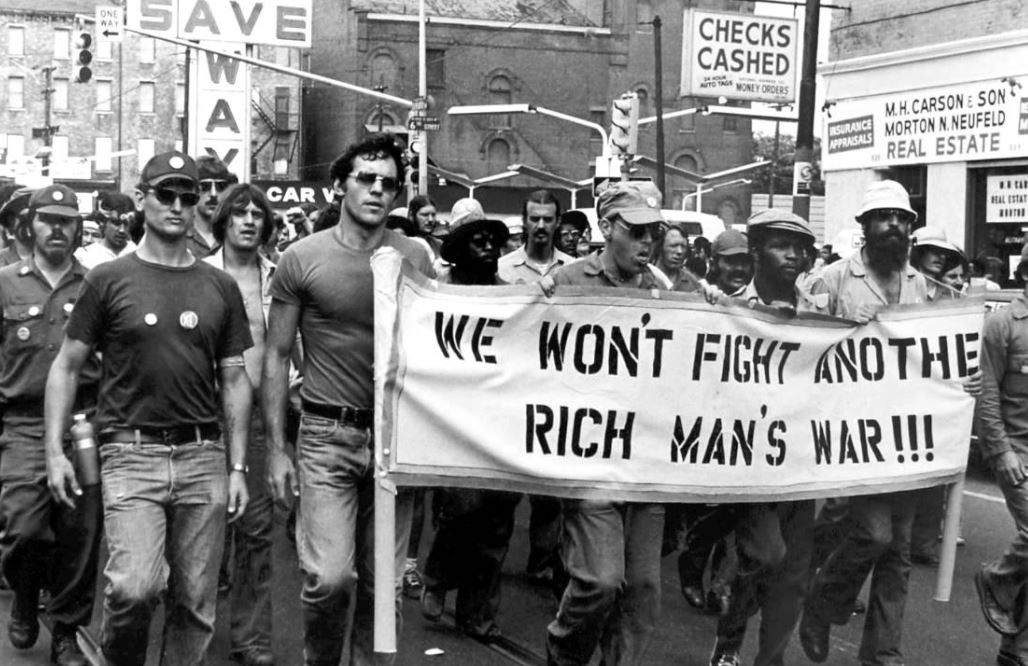

The Antiwar Movement

Even though very few people continued to support the war in Indochina, President Nixon feared that a retreat would make the United States look weak. As a result, instead of ending the war, Nixon and his aides devised ways to make it more palatable, such as limiting the draft and shifting the burden of combat onto South Vietnamese soldiers. This policy seemed to work at the beginning of Nixon’s term in office. When the United States invaded Cambodia in 1970, however, hundreds of thousands of protestors clogged city streets and shut down college campuses. On May 4, National Guardsmen shot four student demonstrators at an antiwar rally at Kent State University in Ohio. Ten days later, police officers killed two black student protestors at Mississippi’s Jackson State University. Members of Congress tried to limit the president’s power by revoking the Gulf of Tonkin resolution authorizing the use of military force in Southeast Asia, but Nixon simply ignored them. Even after The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, which called the government’s justifications for war into question, the bloody and inconclusive conflict continued. American troops did not leave the region until 1973.

Events

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Post-WWII US Culture