The 1980s

Rise of the New Right

The populist conservative movement known as the New Right enjoyed unprecedented growth in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It appealed to a diverse assortment of Americans, including evangelical Christians; anti-tax crusaders; advocates of deregulation and smaller markets; advocates of a more powerful American presence abroad; disaffected white liberals; and defenders of an unrestricted free market.

Historians link the rise of this New Right in part to the growth of the so-called Sunbelt, a mostly suburban and rural region of the Southeast, Southwest and California, where the population began to expand after World War II and exploded during the 1970s. This demographic shift had important consequences. Many of the new Sunbelters had migrated from the older industrial cities of the North and Midwest (the “Rust Belt”). They did so because they had grown tired of the seemingly insurmountable problems facing aging cities, such as overcrowding, pollution and crime. Perhaps most of all, they were tired of paying high taxes for social programs they did not consider effective and were worried about the stagnating economy. Many were also frustrated by what they saw as the federal government’s constant, costly and inappropriate interference. The movement resonated with many citizens who had once supported more liberal policies but who no longer believed the Democratic Party represented their interests.

The Reagan Revolution and Reaganomics

During and after the 1980 presidential election, these disaffected liberals came to be known as “Reagan Democrats.” They provided millions of crucial votes for the Republican candidate, the personable and engaging former governor of California, Ronald Reagan (1911-2004). Once a Hollywood actor, his outwardly reassuring disposition and optimistic style appealed to many Americans. Reagan was affectionately nicknamed “the Gipper” for his 1940 film role as a Notre Dame football player named George Gipp.

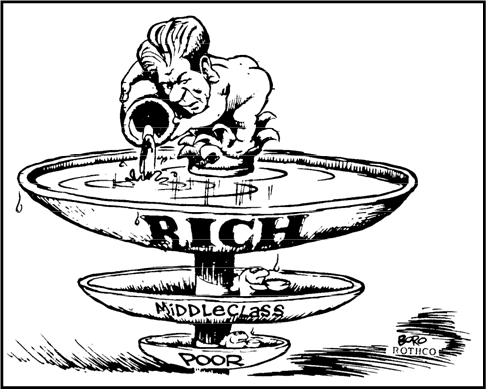

Reagan’s campaign cast a wide net, appealing to conservatives of all stripes with promises of big tax cuts and smaller government. Once he took office, he set about making good on his promises to get the federal government out of Americans’ lives and pocketbooks. He advocated for industrial deregulation, reductions in government spending and tax cuts for both individuals and corporations, as part of an economic plan he and his advisors referred to as “supply-side economics.” Rewarding success and allowing people with money to keep more of it, the thinking went, would encourage them to buy more goods and invest in businesses. The resulting economic growth would “trickle down” to everyone.

Reagan’s economic policies initially proved less successful than its partisans had hoped, particularly when it came to a key tenet of the plan: balancing the budget. Huge increases in military spending (during the Reagan administration, Pentagon spending would reach $34 million an hour) were not offset by spending cuts or tax increases elsewhere. By early 1982, the US was experiencing its worst recession since the Great Depression. Nine million people were unemployed in November of that year. Businesses closed, families lost their homes and farmers lost their land. The economy slowly righted itself, however, and “Reaganomics” grew popular again. Even the stock market crash of October 1987 did little to undermine the confidence of middle-class and wealthy Americans in the president’s economic agenda. Many also overlooked the fact that Reagan’s policies created record budget deficits: In his eight years in office, the federal government accumulated more debt than it had in its entire history.

The End of the Cold War

Like many other American leaders during the Cold War, President Reagan believed that the spread of communism anywhere threatened freedom everywhere. As a result, his administration was eager to provide financial and military aid to anticommunist governments and insurgencies around the world. This policy, applied in nations including Grenada, El Salvador and Nicaragua, was known as the Reagan Doctrine.

In November 1986, it emerged that the White House had secretly sold arms to Iran in an effort to win the freedom of US hostages in Lebanon, and then diverted money from the sales to Nicaraguan rebels known as the Contras. The Iran-Contra affair, as it became known, resulted in the convictions–later reversed–of Reagan’s national security adviser, John Poindexter (1936-), and Marine Lt. Col. Oliver North (1943-), a member of the National Security Council

Popular Culture

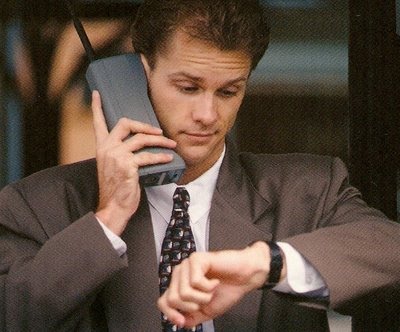

In some respects, the popular culture of the 1980s reflected the era's political conservatism. For many people, the symbol of the decade was the "yuppie": a baby boomer with a college education, a well-paying job and expensive taste. Many people derided yuppies for being self-centered and materialistic, and surveys of young urban professionals across the country showed that they were, indeed, more concerned with making money and buying consumer goods than their parents and grandparents had been. However, in some ways yuppiedom was less shallow and superficial than it appeared. Popular television shows like thirtysomething and movies like The Big Chill and Bright Lights, Big City depicted a generation of young men and women who were plagued with anxiety and self-doubt. They were successful, but they weren't sure they were happy.

At the movie theater, the 1980s was the age of the blockbuster. Movies like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Return of the Jedi, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Beverly Hills Cop appealed to moviegoers of all ages and made hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office. The 1980s was also the heyday of the teen movie. Films like The Breakfast Club, Some Kind of Wonderful, and Pretty in Pink are still popular today.

At home, people watched family sitcoms like The Cosby Show, Family Ties, Roseanne, and Married...with Children. They also rented movies to watch on their new VCRs. By the end of the 1980s, 60% of American television owners got cable service–and the most revolutionary cable network of all was MTV, which made its debut on August 1, 1981. The music videos the network played made stars out of bands like Duran Duran and Culture Club and made megastars out of artists like Michael Jackson, whose elaborate "Thriller" video helped sell 600,000 albums in the five days after its first broadcast. MTV also influenced fashion: people across the country (and around the world) did their best to copy the hairstyles and fashions they saw in music videos. In this way, artists like Madonna became (and remain) fashion icons.

As the decade wore on, MTV also became a forum for those who went against the grain or were left out of the yuppie ideal. Rap artists such as Public Enemy channeled the frustration of urban African Americans into their powerful album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. Heavy metal acts such as Metallica and Guns N’ Roses also captured the sense of malaise among young people, particularly young men. Even as Reagan maintained his popularity, popular culture continued to be an arena for dissatisfaction and debate throughout the 1980s.

Events

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Post-WWII US Culture