The Construction of the Bible

The Documentary Hypothesis

Literary analysis shows that the Pentateuch was not written by one person. Multiple strands of tradition were woven together to produce the Torah.

The view that is persuasive to most of the critical scholars of the Pentateuch is called the Documentary Hypothesis, or the Graf-Wellhausen Hypothesis, after the names of the 19th-century scholars who put it in its classic form.

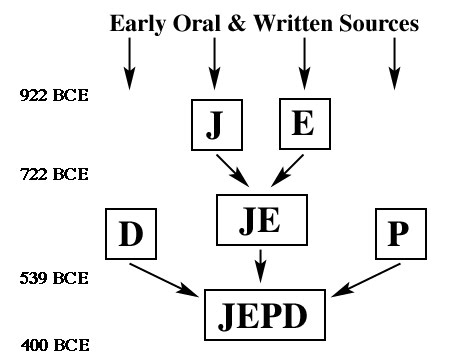

Briefly stated, the Documentary Hypothesis sees the Torah as having been composed by a series of editors out of four major strands of literary traditions. These traditions are known as J, E, D, and P. We can diagram their relationships as follows.

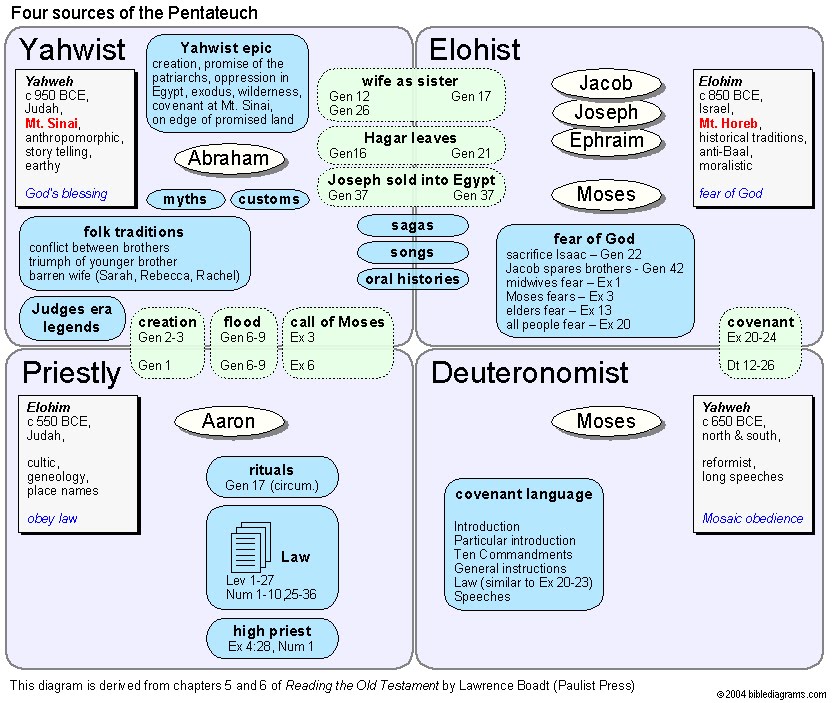

J (the Jahwist or Jerusalem source) uses the Tetragrammaton as God's name. This source's interests indicate it was active in the southern Kingdom of Judah in the time of the divided Kingdom. J is responsible for most of Genesis.

E (the Elohist or Ephraimitic source) uses Elohim ("God") for the divine name until Exodus 3-6, where the Tetragrammaton is revealed to Moses and to Israel. This source seems to have lived in the northern Kingdom of Israel during the divided Kingdom. E wrote the Aqedah story and other parts of Genesis, and much of Exodus and Numbers.

J and E were joined fairly early, apparently after the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE. It is often difficult to separate J and E stories that have merged.

P (the Priestly source) provided the first chapter of Genesis; the book of Leviticus; and other sections with genealogical information, the priesthood, and worship. According to Wellhausen, P was the latest source and the priestly editors put the Torah in its final form sometime after 539 BCE. Recent scholars (for example, James Milgrom) are more likely to see P as containing pre-exilic material.

D (the Deuteronomist) wrote almost all of Deuteronomy (and probably also Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings). Scholars often associate Deuteronomy with the book found by King Josiah in 622 BCE (see 2 Kings 22).

Contemporary critical scholars disagree with Wellhausen and with one another on details and on whether D or P was added last. But they agree that the general approach of the Documentary Hypothesis best explains the doublets, contradictions, differences in terminology and theology, and the geographical and historical interests that we find in various parts of the Torah.

Here are some differences between the four strands of tradition:

| J - JAHWIST | E - ELOHIST | P - PRIESTLY | D - DEUTERONYMIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| stress on Judah | stress on northern Israel | stress on Judah | stress on central shrine |

| stresses leaders | stresses the prophetic | stresses the cultic | stresses fidelity to Jerusalem |

| anthropomorphic speech about God | refined speech about God | majestic speech about God | speech recalling God's work |

| God walks and talks with us | God speaks in dreams | cultic approach to God | moralistic approach |

| God is YHWH | God is Elohim (until Ex 3) | God is Elohim (until Ex 3) | God is YHWH |

| uses "Sinai" | Sinai is "Horeb" | has genealogies and lists | has long sermons |

For further information about the Documentary Hypothesis and the reasons that scholars accept it, see the article "Torah (Pentateuch)" in the Anchor Bible Dictionary.

Genesis Sources

Eugene H. Maly provides this outline of Genesis with tentative ascription to the Yahwist, Elohist, and Priestly sources. (The Jerome Biblical Commentary, pp. 9-10)

- Primitive History (1 - 11)

- Creation of World and Man (1:1-2:4a) (P)

- Creation of Man and Woman (2:4b-25) (J)

- The Fall (3:1-24) (J)

- Cain and Abel (4:1-16) (J)

- Genealogy of Cain (4:17-26) (J)

- Genealogy of Adam to Noah (5:1-32) (P)

- Prologue to the Flood (6:1-22) (J and P)

- The Flood (7:1-8:22) (J and P)

- The Covenant with Noah (9:1-17) (P)

- The Sons of Noah (9:18-27) (J)

- The Peopling of the Earth (10:1-32) (P and J)

- The Tower of Babel (11:1-9) (J)

- Concluding Genealogies (11:10-32) (P and J)

- The Patriarch Abraham (12:1 - 25:18)

- The Call of Abram (12:1-9) (J, P)

- Abram and Sarai in Egypt (12:10-20) (J)

- The Separation of Abram and Lot (13:1-18) (J, P)

- Abram and the Four Kings (14:1-24) (?)

- Promises Renewed (15:1-20) (J, E?)

- Hagar's Flight (16:1-16) (J, P)

- The Covenant of Circumcision (17:1-27) (P)

- Promise of a Son; Sodom and Gomorrah (18:1-19:38) (J)

- Abraham and Sarah in Gerar (20:1-18) (E)

- Isaac and Ishmael (21:1-21) (J and P)

- Abraham and Abimelech (21:22-34) (E)

- The Sacrifice of Isaac (22:1-24) (E, J)

- The Purchase of the Cave of Machpelah (23:1-20) (P)

- The Wife of Isaac (24:1-67) (J)

- Abraham's Descendants (25:1-18) (P and J)

- The Patriarchs Isaac and Jacob (25:19 - 36:43)

- The Birth of Esau and Jacob (25:19-34) (J, P)

- Isaac in Gerar and Beer-sheba (26:1-35) (J, P)

- Isaac's Blessing of Jacob (27:1-45) (J)

- Jacob's Departure for Paddan-aram (27:46-28:9) (P)

- Vision at Bethel (28:10-22) (J and E)

- Jacob's Marriages (29:1-30) (J, E?)

- Jacob's Children (29:31-30:24) (J and E)

- Jacob Outwits Laban (30:25-43) (J, E)

- Jacob's Departure (31:1-21) (E, J)

- Laban's Pursuit (31:22-42) (E, J)

- The Contract Between Jacob and Laban (31:43-32:3) (J and E)

- Preparation for the Meeting with Esau (32:4-22) (J and E)

- Jacob's Struggle with God (32:23-33) (J)

- Jacob's Meeting with Esau (33:1-20) (J, E?)

- The Rape of Dinah (34:1-31) (J and E)

- Jacob at Bethel (35:1-29) (E and P)

- The Descendants of Esau (36:1-43) (P?)

- The History of Joseph (37:1 - 50:26)

- Joseph Sold into Egypt (37:1-36) (J and E)

- Judah and Tamar (38:1-30) (J)

- Joseph's Temptations (39:1-23) (J)

- Joseph Interprets the Prisoners' Dreams (40:1-23) (E)

- Joseph Interprets Pharaoh's Dreams (41:1-57) (E, J)

- First Encounter of Joseph with His Brothers (42:1-38) (E, J)

- Second Journey to Egypt (43:1-34) (J, E)

- Judah's Plea for Benjamin (44:1-34) (J)

- The Recognition of Joseph (45:1-28) (J and E)

- Jacob's Journey to Egypt (46:1-34) (J, E, and P)

- The Hebrews in Egypt (47:1-31) (J and P)

- Jacob Adopts Joseph's Sons (48:1-22) (J and E, P)

- Jacob's Blessings (49:1-33) (J?)

- The Burial of Jacob and the Final Acts of Joseph (50:1-26) (J, E, and P)

Criticism of the Documentary Hypothesis

While the Documentary Hypothesis dominated biblical scholarship, especially in the US, throughout the 20th century, it came under more critical scrutiny during the 1980s and is today no longer quite so dominant as it once was. No serious biblical scholars deny the idea that the origins of the Pentateuch lie with multiple sources; instead, it's the number and identity which is more generally debated now than it was 50 years ago.

The main problem is that the Documentary Hypothesis tends to assume separate, complete books being brought together by multiple editors over time. This is difficult to reconcile with the text we have, because scholars acknowledge that the numerous editors and redactors of these texts should have done a better job of creating a consistent work from their sources. But it's precisely the inconsistencies which led scholars to develop the conclusion that multiple sources were used.

More targeted reservations about the Documentary Hypothesis don't argue for fewer sources, but about how these sources, and potentially others, are characterized. The Documentary Hypothesis has been illegitmately used to priviliege or condemn contemporary religious traditions. For instance, there's the (not necessarily supported) contention that J is the earliest source, and is an example of ethical monotheism. (Ethical monotheism states that there is one God from whom emanates one morality for all humanity, and that God's primary demand of people is that they act decently toward one another. Therefore, any passage within the Pentateuch that doesn't fit a (typically) Protestant theology of God or what it means to be the people of God, is considered to be in some sense a later corruption (especially anything within the P tradition). This position denigrates Judaism as it was and is practiced, in that any quality of Judaism that deviates from modernist Protestantism (dietary laws, clothing laws, slavery laws, etc.) is labelled a later corruption.

Christine Hayes has a great summary of other issues:

It needs to be remembered that the documentary hypothesis is only a hypothesis. An important and a useful one, and I certainly have used it myself. But none of the sources posited by critical scholars has been found independently: we have no copy of J, we have no copy of E, we have no copy of P by itself or D by itself. So these reconstructions are based on guesses. Some of them are excellent, excellent guesses, very well supported by evidence, but some of them are not. Some of the criteria invoked for separating the sources are truly arbitrary, and extraordinarily subjective. They are sometimes based on all sorts of unfounded assumption about the way texts were composed in antiquity, and the more that we learn about how texts in antiquity were composed, we realize [for example] that it's perhaps not unusual for a text to use two different terms for the same thing within one story, since we find texts in the sixteenth, seventeenth century BCE on one tablet using two different terms to connote the same thing.

So while there is no new theory or hypothesis about the construction of the Pentateuch to supplant the Documentary Hypothesis, contemporary scholars have been less interested in embracing it wholesale.

Sources:

Boadt, Lawrence. Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press, 1984.

Friedman, Richard Elliott. "Torah (Pentateuch)" in The Anchor Bible Dictionary.

Hayes, Christine. "Introduction to the Old Testament. Lecture 5: Critical Approaches to the Bible: Introduction to Genesis 12-50." Youtube.com, uploaded by YaleCourses, 6 December 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBSOn0MSrk8

Plaut, W. Gunther, editor. The Torah: A Modern Commentary. Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.