Boland's Poetry

The Dolls Museum in Dublin

|

The wounds are terrible. The paint is old. |

When EB's family was young, they were living in Dundrum, south of Dublin. The Dolls Museum was a short drive away (now it's at Powerscourt), and EB would often take her children there. It was a "room with high glass cases crowded with dolls, you could see their faces, the old craft and art, before plastics."  What did these dolls mean in the era before plastics, which was also the era of nation-making in Ireland? These fast-moving historical events happened in the presence of deeply inert objects.  These "strange, almost ominous, inert emblems of childhood, and the idea of the Easter Rebellion and the way the children must have clasped those dolls in a history-less moment.  This is about where history is and is not recorded. The dolls do not feel or know anything; they're ignorant of the history they have witnessed, and instead have "the stupor that ensues from digesting a history and identity that is not one's own."  |

The Pomegranate

|

The only legend I have ever loved is |

Fat and full of red juice and sweet, crunchy, ruby-red seeds bursting from it when it is split, the pomegranate has traditionally been a symbol of fertility, and, more recently, of female sexuality. It was considered an aphrodisiac and often presented at weddings. Ancient Sumerians believed that only after the souls of the dead ate pomegranate seeds in the underworld did they become immortal.

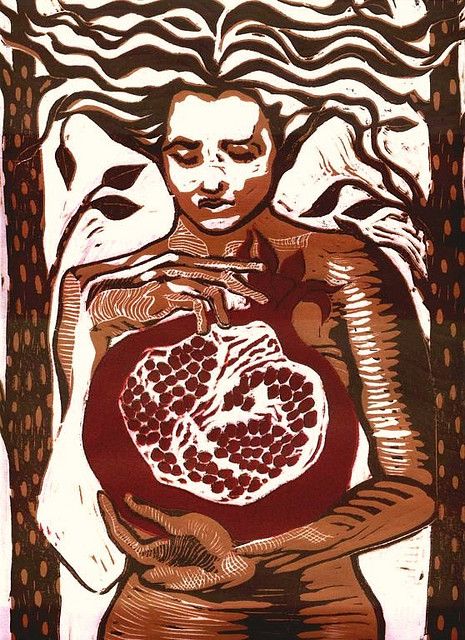

Persephone, Linoleum Block Print, by Miriam Sanders (2007) The Greeks used the story of Demeter and Persephone to explain the changes in seasons. But it's also about the power of parental love, and what lengths a mother will go to to protect her child.

Demeter Mourning for Persephone, by Evelyn De Morgan (1906) Boland's first experience of the myth is as the daughter and victim. She acknowledges being taken from all that she knew, all that she called home, and growing up in a strange place, exiled.

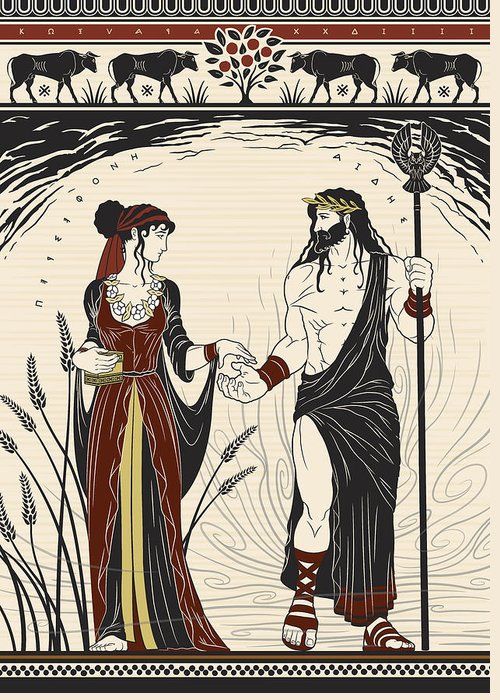

Hades and Persephone, by Matthew Kocvara (2014) Now, however, she sees the other side, and is the one who will have to let go. She has moved from one heartbreak to another. |

In Which the Ancient History I Learn is Not My Own

|

The linen map |

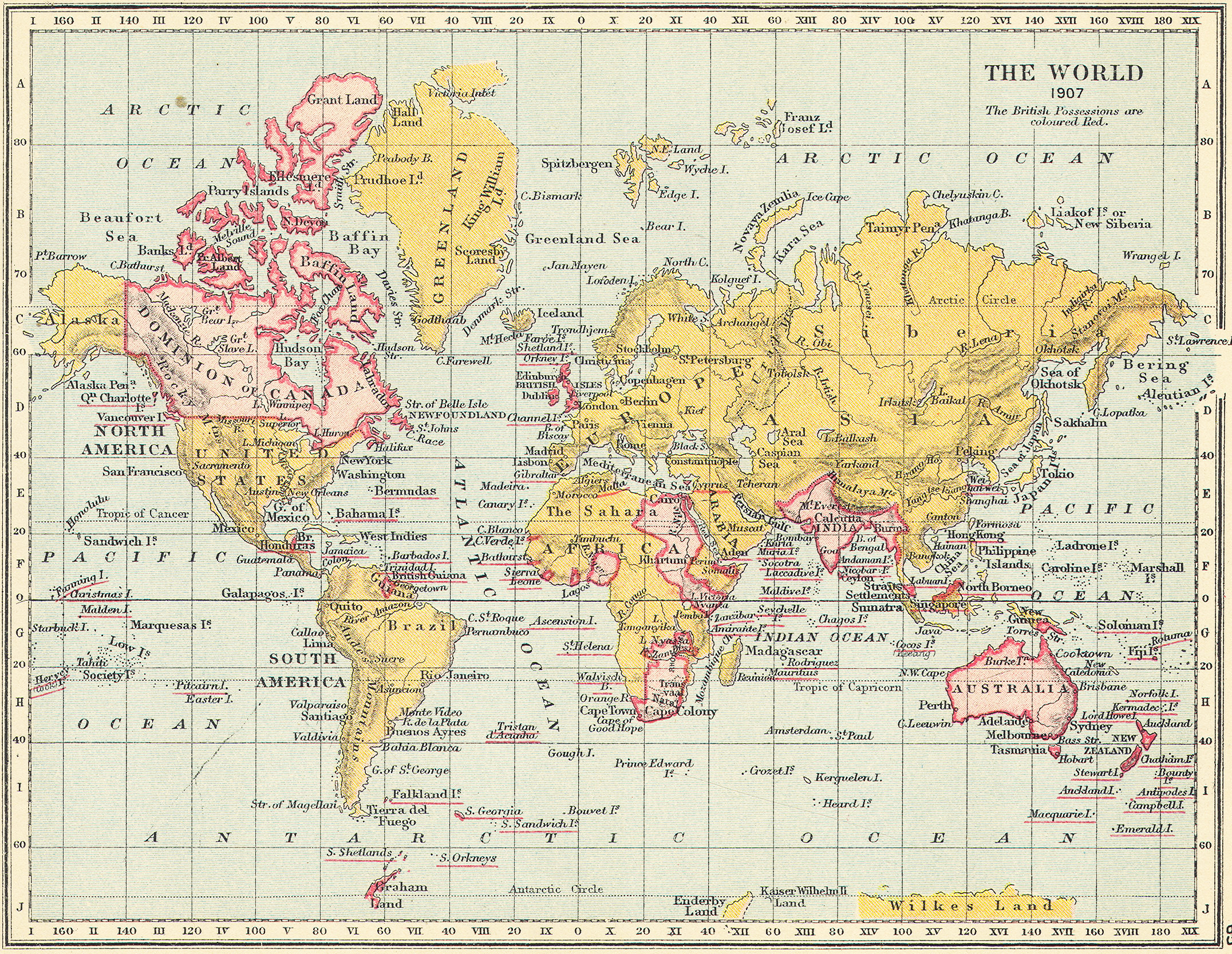

Given the nature of primary education in England in the 1950s, this is probably the type of map that Boland saw in her classroom. Everything from the coloration to the projection to the centering of the map itself promotes British primacy. But the specter of this map sits behind what Boland saw. |

Quarantine

|

In the worst hour of the worst season |

Throughout the west and southwest of Ireland, there are a hundreds of tracks and pathways crossing the hills and valleys in the most obscure places, all seemingly going from nowhere to nowhere. These are the Famine Roads.

From 1845 to 1852 Ireland experienced an Gorta Mór, or the Great Hunger, a famine so severe that it is considered the worst peacetime humanitarian crisis in Europe since the Black Death in the 14th century. The most severely affected areas were in the west and south of Ireland. During the Great Hunger, over 1 million people died and almost 2 million more left the country. Ireland was then part of the United Kingdom, but initial British attempts to relieve the famine in 1845 were halted in 1846 when the Whigs took over the government administration. The famine roads were part of a project initially conceived by Robert Peel's Conservative government to improve infrastructure in Ireland and thereby strengthen the economy, while also providing paid employment for those without other means of sustenance following the failure of the potato crop in 1845. But the project was not executed well, and funding arrangements didn't always work out. British government officials thought that local landlords (themselves absentees who lived in England) were skimming money from the project.

But all of this was moot by 1846, when Peel was forced to step down and Whig John Russell became Prime Minister. By October of 1846 it was clear that over 90% of the potato crop of Ireland was blighted, and famine conditions were growing worse. Russell set out his approach to the famine: "It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people. . . . We can at best keep down prices where there is no regular market and prevent established dealers from raising prices much beyond the fair price with ordinary profits." His policies focused on finding work rather than food for the famine victims, because he believed that private enterprises, not the government, should be responsible for providing food to those who could afford it. He also stressed that any costs for this relief project should be paid by the Irish, not the English. Russell also insisted that Ireland continue to export grain to England. From 1843 to 1846, Ireland exported over over 2.73 million tons of grain to England. So while tens of thousands of people in Ireland starved to death or died of exposure in the winter of 1846, the country was still forced to export over half a million tons of grain to England.

In August of 1846 Russell selected Charles Trevelyan to oversee the government relief program. But Trevelyan limited the food aid program, because, he claimed, food would be imported into Ireland once people had more money to spend after wages were being paid on public-works projects like the famine roads and urban workhouses. He stated that The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson and that calamity must not be too mitigated [..] The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people. Beyond seeing this disaster as some sort of divine corrective for the Irish national character, he also saw the continuance of the famine as an opportunity. In a letter to Edward Twistleton he wrote, We must not complain of what we really want to obtain. If small farmers go, and their landlords are reduced to sell portions of their estates to persons who will invest capital we shall at last arrive at something like a satisfactory settlement of the country.

A lack of tools, the malnutrition of the workers, a spate of terrible weather in the winter of 1846 and the spring of 1847, the starvation wages (which could be as little as three pennies a day), delays in even those paltry payments, official suspicion that local officials were employing people who really didn't need to be on the project, the inability of the bureaucracy to keep track of all the projects and handle all the payment processes involved, and the fact that the schemes were not preventing the ever-increasing distress of the people, eventually led to their abandonment. |