Kindred — Background

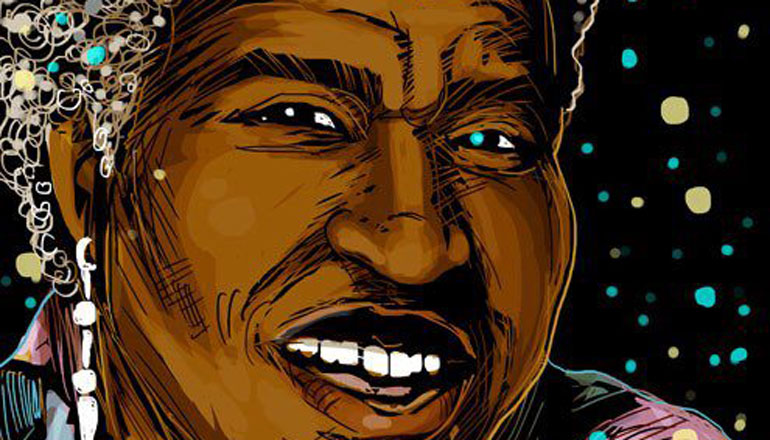

Respect your elders . . .

Butler was in school during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Black Power movement and the Black Arts movement were both in full flower. For many of the members of the Black Power movement, it was de rigeur to denigrate their ancestors who were subject to slavery. They insisted that they would have rebelled against any mistreatment. While Butler wasn't really a part of the movement, and wasn't inclined to argue with them publicly, she wrote Kindred as a response to those uninformed insults to enslaved people. She knew that just surviving slavery was an act of bravery, and required great sacrifices along with a great strength of will.

The violence in this book is inescapable; for an enslaved person to fight against it was to invite physical torture or death.

It was even worse than it looks

Butler wanted to present a realistic portrayal of slavery, but in doing the research for this book, she realized that she just couldn't fully illustrate the violence inherent in slaving and still sell books — the reading public would be both offended and horrified if they actually read about the day-to-day life and the almost casual violence visited upon enslaved people. So she really toned all that down for her work here. Remember that when you see the brutality here; the reality of this life was far worse.

More races, more problems

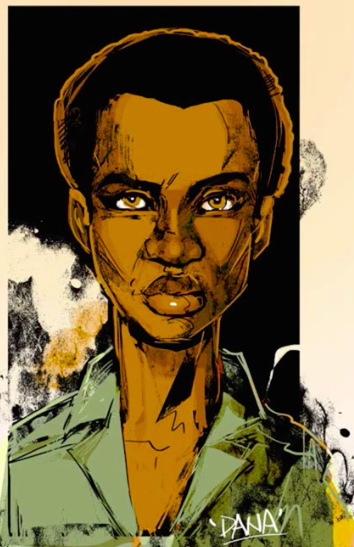

The Dana of 1976 is in a mixed-race relationship with Kevin. The boy whose fear calls Dana back to 1815 Maryland is Rufus, who is also involved in a "relationship" — and I use that term very loosely — with Alice Greenwood, a free black woman who lives near Rufus's father's plantation. The juxtaposition of the willingness of each member of the two couples to be in a relationship with one another is one of the great ironies of this book.

Get yourself someone like this

Dana's husband, Kevin, instantly believes her astinishing story about travelling back and forth in time. He packs her a survival bag, and plans on travelling back to the past with her the next time she goes. While he's about to go to the library to do research on how to forge a Deed of Manumission ("freedom papers") for Dana, she is transported again. He goes back to the past with her and must pretend to be her owner for several weeks. But then she's transported to her present again, and Kevin is left alone for five years in the past, from 1915 to 1820. He spends so much time in the early 19th century that he has difficulties adjusting when he finally gets back to his "real life." That's some serious love and devotion.

Something on the images

Line

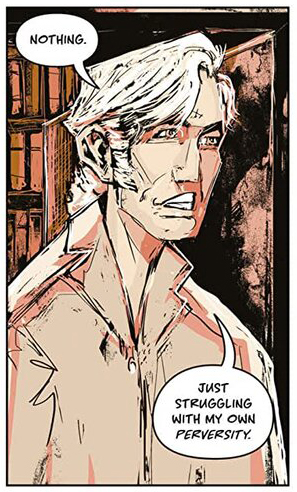

You've noticed that the style of drawing used by Damian Duffy and John Jennings looks rough, as if we're looking at sketches that will eventually become something more refined. But that style was a deliberate choice they made, one designed to reflect the unfinished American project, the incomplete struggle for equal rights for all in the US.

Color

Duffy and Jennings make extensive use of a color called "haint blue." Their use of this color makes their story more universal, as it moves beyond just the Maryland shore to allude to a legend from the Gullah Geechee. These people are descendants of Africans who were enslaved on the rice, indigo and Sea Island cotton plantations. The currently live in the Low Country and on the barrier islands off the coast of the Carolinas, Georgia, and north Florida.

The legend says that this shade of blue tricks “haints” and “boo hags” — evil spirits trapped between the world of the living and the world of the dead, who were set free from their human forms at night to paralyze, injure, ride (the way a person might ride a horse), or kill innocent victims — into believing that they’ve stumbled into water (which they cannot cross) or sky (which will lead them farther from the victims they seek). So painting spaces to look like water or sky will keep those spirits away.

Later versions, adopted and adapted by slave owners and other wealthy whites in the area, said that painting your front porch ceiling this color would ward off insects, especially wasps, because it confused them. This idea has become so popular over the years that you can get "haint blue" paint in at least nine different shades from paint manufacturers like Benjamin Moore, Sherwin Williams, Valspar, Pratt & Lambert, and Harrow & Ball.

The color itself comes from the dye made by crushing indigo plants, when indigo was a common crop for plantations in the American South. That dye was mixed with lime as a thickener (among other ingredients). Lime naturally repels insects, so this is probably how the color got its reputation for keeping bugs away.

Of course, there's another reason why Duffy and Jennings made such liberal use of this color: Dana is, in many ways, a ghost, haunting her own past. We don't understand the mechanism that creates the pathway between 1976 and 1815, but when she is transported back to Maryland, she is surrounded by beings who are dead in 1976, whileshe herself will not be born for more than a century. She bounces between the worlds of the living, the dead, and the not-yet-living throughout this text.

Past and Present

Butler's text is all about how we can never really know the past, and we cannot escape its influence on the present. So let's talk about some history first:

The first enslaved people in what was later to become the US were a group of between 20 and 30 Africans who were transported to the English colony of Virginia, where they were sold to colonists. For the next 246 years, or, in other terms, for the next eight generations of Americans, slavery was a part of the national fabric.

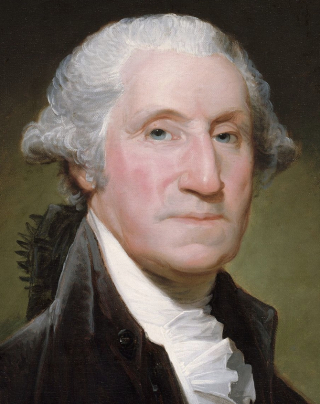

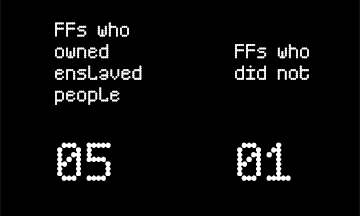

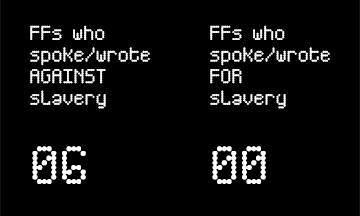

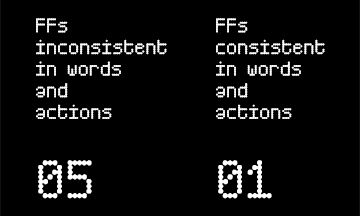

We've all seen the contradictory claims made by opposing political factions: "The Founding Fathers all oposed slavery" or "The Founding Fathers were all enslavers." The truth is, neither side can paint with so broad a brush.

Even the term "Founding Fathers" is complicated. When we say "The Founding Fathers," we usually mean the men who led the American Revolution, who united the colonies, led the American effort for independence, and initially structured the US government. Most, if not all, historians would agree that Washington, Jefferson, Madison, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and Benjamin Franklin were all Founding Fathers. But beyond these six, the disagreements start. Some historians say that all those who signed the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution are Founders. Other historians include all the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, whether they signed the Constitution or not. More historians say that those who signed the Articles of Confederation (the first constitution of the US, adopted in 1781) are Founders. But let's avoid all those fights about who is and who isn't a Founder, and just stick with the Big Six above.

The short answer is yes. Here's the breakdown:

George Washington owned hundreds of enslaved people. When he was 11 years old (in 1743), he first became a slaver when he inherited 10 enslaved people. He acquired more through other inheritances. Between 1752 and 1773, he purchased at least 71 slaves — men, women and children. When he married Martha Custis in 1761, he gained control of 84 "dower slaves," whom Martha had inherited upon the death of her first husband. At the time of Washington's death, the Mount Vernon estate’s enslaved population consisted of 317 people. 124 were owned outright by Washington, 40 were rented, and the remaining 153 were owned by the estate of Martha’s first husband on behalf of their grandchildren.

But he freed them all in his will, right?

Nope. In his will, Washington freed exactly one enslaved person: his valet, William Lee, a man whom he purchased over 30 years prior. He had no right to free the rented or dower slaves, and did not free any of the remaining 123 slaves that he himself owned.

Thomas Jefferson enslaved over 600 human beings throughout the course of his life. 400 of these people people were enslaved at Monticello (with roughly 130 of them in bondage there at any given time); the other 200 people were held on Jefferson’s other properties. Unlike Washington, Jefferson didn't buy many enslaved people (fewer than 20). He inherited about 40 from the estate of his father in 1764, and 135 upon the death of his father-in-law in 1774. But he acquired most of the people he held in bondage through what we euphemistically call "the natural increase of enslaved families." That is, he bred them. And yeah, he reeeallllly bred them.

No! Not the guy who wrote "All men are created equal"!

Yep. Throughout the whole of his slaveowning career, TJ freed seven enslaved men. Two were freed during his lifetime, and five were freed in his will. We don't have enough time or space here to explore his relationship with Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman with whom he had several children, but it says enough about his character to know that he enslaved HIS OWN CHILDREN. He had six children with Sally, four of whom lived to adulthood. He enslaved them all for various periods of time, and never, not even in his will, freed the mother of his children. Sally was never legally emancipated. Instead, she was unofficially freed, or “given her time,” by Jefferson’s daughter Martha after his death.

James Madison was raised on a plantation that made use of slave labor. He saw the institution of slavery as a necessary part of the Southern economy. When he was at his most financially successful point, around 1801 (when he became Secretary of State for Jefferson), Madison owned a little over 100 enslaved people. But after his presidency he ran into serious financial problems and so had to sell both land and enslaved people. At his death in 1836 he owned 36 enslaved people. He did not free any of those people he owned, both during his lifetime and in his will.

John Adams did not own enslaved people. Instead, the Adamses hired white and free African-American workers to provide these services. However, that did not mean that they avoided slavery altogether. While the Adamses opposed slavery both morally and politically, they tolerated the practice in their daily lives and they may have hired out enslaved African Americans, paying wages to their owners, to work in the Vice President’s and President’s House.

After his Presidency, Adams served in Congress for eighteen years, where he often spoke out against the organized political power of the slave owners who dominated representation of all southern states in Congress. He also opposed the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War as "conspiracies to extend slavery." In 1836 the House of Representatives had instituted a gag order, than no talk of abolition could occur in Congress. Adams refused to follow the order, and in 1842 those slave-owning southern representatives whom he railed against sought to have him censured. In 1844 the gag order was lifted, and Henry Wise, a slave-owning representative from Virginia and a staunch enmy of Adams, called him "the acutest, the astutest, the archest enemy of southern slavery that ever existed." Adams said he took great delight in knowing that this is how all southerners would remember him.

Despite the way he's been portrayed on Broadway, recent evidence (including his own household cashbook) proves that Alexander Hamilton owned enslaved people. (See Jessie Serfilippi's “As Odious and Immoral a Thing": Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden History as an Enslaver.) It's long been known that Hamilton bought and sold enslaved people for his in-laws, but Serfilippi's work is incontrovertible about Hamilton himself. Historian William Hogeland notes, “Her [Serfilippi's] research confirms what we have suspected, and it takes the whole discussion to a new place. She’s found some actual evidence of enslavement on the part of Hamilton that is just more thoroughgoing and more clearly documented than anything we’ve had before.”

Prior to this 2020 revelation, the standard take on Hamilton and slavery was that his personal and professional lives were at odds with one another. While he often argued for the emancipation of enslaved people, and was also a member of the New York Manumission Society, he also acted as legal arbiter for others in the transactions of people in bondage. So he put aside his personl scruples when it came to paying the bills. Now, however, we can see his personal and professional lives as more in line with one another, and consider the mental and moral gymnastics he must have put himself through when he said one thing and did another.

As a young man, Ben Franklin owned enslaved people. As a printer and publisher, he carried advertisements for the sale of enslaved people in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. At the same time, however, he published pamphlets against slavery and condemned the practice of slavery in his private correspondence. But later in life he became an outspoken opponent of slavery. In 1787 became the President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. In 1789 he wrote and published several essays supporting the abolition of slavery. His last public act was to send to Congress a petition on behalf of the Society asking for the abolition of slavery and an end to the slave trade. The 1790 petition asked the first US Congress to "devise means for removing the Inconsistency from the Character of the American People," and to "promote mercy and justice toward this distressed Race."

Of course, this petition was immediately denounced by pro-slavery representatives from the southern states. The Senate took no action on it, and the House referred it to a select committee, who eventually reported that it was against the US Constitution to emancipate any enslaved person until 1808.

Now what can we infer from those two scores?

We could call this their hypocrisy scoreboard, but let's be generous and just leave it at this:

12 of the first 18 Presidents of the US owned enslaved people.

Well, not really. We could push all this away from us, make it a global issue, and use the definition of "Modern Slavery" that the US Department of State offers:

“Trafficking in persons,” “human trafficking,” and “modern slavery” are used as umbrella terms to refer to both sex trafficking and compelled labor. [US Acts and Protocols] describe this compelled service using a number of different terms, including involuntary servitude, slavery or practices similar to slavery, debt bondage, and forced labor.

Let's connect that definition from this directive from the Federal Bureau of Prisons:

Sentenced inmates are required to work if they are medically able. Institution work assignments include employment in areas like food service or the warehouse, or work as an inmate orderly, plumber, painter, or groundskeeper. Inmates earn 12¢ to 40¢ per hour for these work assignments.

That directive sure looks like it has something to do with things like "compelled service," "involuntary servitude," "debt bondage," or "forced labor."

Let's see if there are others who look at this in the same light:

Incarcerated persons or, more specifically, the “duly convicted,” lack a constitutional right to be free of forced servitude. Further, this forced labor is not checked by many of the protections enjoyed by workers laboring in the exact same jobs on the other side of the 20-foot barbed-wire electric fence."

— Whitley Benns, "American Slavery, Reinvented." The Atlantic, 21 September, 2015.

Starbucks holiday products, and McDonald’s uniforms have all been made (or are still made) with low-wage prison labor. 40% of the firefighters battling California’s forest fires are prison inmates working for $2 an hour.

— Annie McGrew. "It’s Time to Stop Using Inmates for Free Labor." TalkPoverty, 20 October, 2017.

It did, in every instance except one: as punishment for a crime. In many US states, as well as in the federal system, these "exception clauses" allow prisons to explout, underpay, and exclude incarcerated workers from workplace safety protection laws.

These exception clauses were one of the tools used by racists during the Jim Crow era to imprison and re-enslave Black people. And they're manifestations of systemic racism right now.

There are currently (2023) more than 1,900,000 people incarcerated in the US. The overwhelming majority of these incarcerated people are workers. While the jobs that most of them do look just like jobs they would have if they weren't imprisoned, there are a couple of serious differences:

- incarcerated workers are under the complete control of their employers, and

- incarcerated workers have no protection against labor exploitation and abuse.

Regular prison jobs. These are directed by the Department of Corrections and support the prison facility. This category includes custodial, maintenance, laundry, grounds keeping, food service, and many other types of work. Sometimes called “facility,” “prison,” or “institutional support” jobs, these are the most common prison jobs, done by over 80% of incarcerated workers.

Jobs in "Correctional Industries" These state-owned businesses produce goods and provide services that are sold to government agencies. Correctional agencies and the businesses coordinate to operate these “shops,” and the revenues they generate help fund these positions. Agency-operated industries employ about 6% of people incarcerated in prisons. 49 states run these businesses (AK is the only exception).

Jobs outside the facility. Work release programs, work camps, and community work centers provide services for public or nonprofit agencies. These programs are directed by the Department of Corrections, but sometimes community employers pay incarcerated workers’ wages. These jobs are typically reserved for people considered lower security risks, and/or those preparing to be released.

Jobs in private businesses. A small number of incarcerated people work for businesses that contract with correctional agencies through the PIE program. This program allows private companies to operate within correctional facilities and provide job training and supervision.

Sure they do, like little kids with lemonade stands. Wages vary with the job. Here's their wage scale:

| Type of job | # employed (%) |

Highest hourly wage (state) |

Lowest hourly wage (state) |

Low avg. hourly wage |

High avg. hourly wage |

| Regular prison jobs | > 1,000,000 (> 53%) |

$2.00 (NJ) |

$0.00 (AL, AK, GA, MS, SC, TX) |

14 ¢ | 63 ¢ |

| Correctional Industries | ~ 67,000 (3.5%) |

$4.90 (AK) |

$0.00 (AK, GA, OK, TX) |

33 ¢ | $1.41 |

| Outside the facility | ~ 10,000 (< ½%) |

$4.00 (NV) |

$0.00 (AK, GA, MS, SC, TX) |

25 ¢ | 85 ¢ |

| Private businesses | ~ 5,000 (< ⅕%) |

20% of "prevailing local wages"* (All) |

20% of "prevailing local wages"* (All) |

NA | NA |

* Note: "Prevailing local wages" is the de jure wage rate. However, up to 80% of any prisoner's wages may be taken by the system or facility for victim restitution funds, court costs, an individual's "room and board," and fees to maintain and build more prisons. While these deductions are taken from prisoners in all four categories, they are far more likely to be taken from workers in this category, since these wages come from outside the prison system.

The big money ends up back in the prison systems (federal, state, and for-profit) and in state governments. In 2022, incarcerated workers in the US produced more than $2,000,000,000 in goods and more than $9,000,000,000 in services.