Enclosure, Anti-Vagrancy Laws, and the Rise of the Urban Poor

or, Why Swift Was Always So Pissed Off

English Folk Poem - a number of versions circa 1700s

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own,

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who take things that are yours and mine.

The poor and wretched don't escape

If they conspire the law to break.

This must be so, but they endure,

Those who conspire to make the law.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.

Enclosure

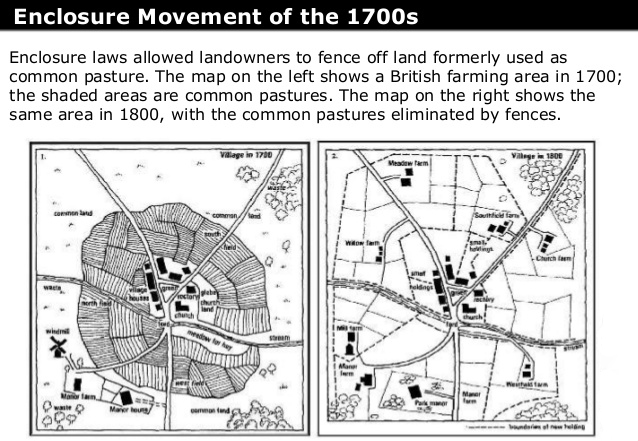

The Enclosure Acts, a series of laws passed by the British Parliament beginning in the 12th century and ending only in 1914, were one factor in the creation of a class of people who moved to the city for work, but found there was little or none. Many times, even when they found work, the wages were not enough to support themselves or their families. Through the Acts, open fields and "wastes," plots of land known as "Commons" and traditionally used by "commoners" were closed to use by the peasantry. Open fields were large agricultural areas to which a village population had certain rights of access and which they tended to divide into narrow strips for cultivation. The wastes were unproductive areas—for example, fens, marshes, rocky land, or moors—to which the peasantry had traditional and collective rights of access in order to pasture animals, harvest meadow grass, fish, hunt, collect firewood, or otherwise benefit. Rural laborers who lived on the margin depended on open fields and the wastes to fend off starvation.

In other words, enclosure consolidates the ownership of land, usually for the stated purpose of making it more productive. The British Enclosure Acts removed the prior rights of local people to rural land they had often used for generations. As compensation, the displaced people were commonly offered alternative land of smaller scope and inferior quality, sometimes with no access to water or wood. The lands seized by the acts were then consolidated into individual and privately owned farms, with large, politically connected farmers receiving the best land. Often, small landowners could not afford the legal and other associated costs of enclosure and so were forced out.

Forced to leave their homes, with nowhere else to go, the former "commoners" migrated to the cities and swelled the numbers of the urban poor who would later work in the factories that powered the industrial revolution. Others wandered the land as homeless beggars.

By 1699, over 71% of the land in England was enclosed. Despite this, from 1730 to 1839, over 4,000 more enclosure bills were passed by Parliament, obviously adding to that percentage.

As should be obvious, this move was all about rewarding the rich by taking even more from the poor. Here's historian Joseph Stromberg's explanation:

The political dominance of large landowners determined the course of enclosure. . . . [I]t was their power in Parliament and as local Justices of the Peace that enabled them to redistribute the land in their own favor.

A typical round of enclosure began when several, or even a single, prominent landholder initiated it . . . by petition to Parliament. . . . [T]he commissioners were invariably of the same class and outlook as the major landholders who had petitioned in the first place, [so] it was not surprising that the great landholders awarded themselves the best land and the most of it, thereby making England a classic land of great, well-kept estates with a small marginal peasantry and a large class of rural wage labourers. (35)

By the middle of the 18th century, enclosures created a veritable army of industrial reserve labor, for farms and factories.

There were other factors that contributed to the desperation of the urban poor. The loss of cottage industries, for instance, also had a great influence on their state. The majority of people in pre-Industrial England dwelt in the countryside, where they often supplemented their income through extra work, usually done at the end of a traditional day of farming. The most important one in England was the weaving of wool. In Northern Ireland, it was the tatting of lace. But this income evaporated with the advent of cheap cotton and industrialized methods of weaving it. In both the countryside and the city, the displaced and disenfranchised were reduced to working for starvation wages that they supplemented through prostitution, theft, and other stigmatized or illegal means.

Anti-Vagrancy Laws

The first official English vagrancy statute, the Statute of Labourers, was passed in 1349, when England was still a feudal society. At that time, peasants had already begun to move to urban areas in search of better living conditions (a result of early Enclosure Acts). This was complicated by the number of deaths caused by the plague, and so a labor shortage ensued. The statute made it an offense to give alms to anyone able to work. The law was intended to force anyone who was able to work to do so. In 1360, the statute was amended to further curtail the movement of potential laborers.

If this system looks familiar, it should. This thing has been kicking around for years. In the US, the UK, and Canada it's known as "Workfare," and has been proposed and implemented by conservative politicians, in various forms, since the 1960s. In Australia the same system is known as "mutual obligation." Strictly speaking, workfare means that people who receive financial aid through welfare are required to perform compulsory labour or service as a condition of their assistance. The traditional definition of workfare refers to mandatory participation in a designated activity (Torjman 1)

Sociologist William Chambliss interprets these laws thus: “[t]here is little question that these statutes were designed for one express purpose: to force laborers (whether personally free or unfree) to accept employment at a low wage in order to ensure the landowner an adequate supply of labor at a price he could afford to pay.” So not only would commoners lose the land they previously had a right to, they would also be forced to work for those who had taken that land.

By the 16th century, vagrancy laws were revised to serve the additional purpose of curtailing criminal activities. New laws sought to punish ambiguously-defined persons, such as someone who didn't look like he had a job, or cannot say where or for whom he works. Chambliss backs this up by quoting the actual statute: "For someone who is merely idle and gives no reckoning of how he makes his living the offender shall be:

. . . had to the next market town, or other place where they [the constables] shall think most convenient, and there to be tied to the end of a cart naked, and to be beaten with whips throughout the same market town or other place, till his body be bloody by reason of such whipping.[22 H. 8. c. 12. (1503)]"

Penalties for such offenses were increasingly severe, and included being whipped as above for two days, having an ear cut off, or even facing the death penalty.

Legislators acted in ways that discriminated against the poor with no regard for their human rights. From the 1500s to 1700s, laws provided for various ways of marking paupers (using a “P” applied to the clothes) or branding rogues, vagabonds and slaves (using an “R”, “V” or “S” burnt on the skin with a hot iron). Law enforcement imposed slavery on persistent offenders. During the 1600s, war and famine displaced many persons and led to the enactment of laws allowing parishes to evict from their district strangers potentially requiring assistance from the parish. Essentially, lawmakers were crafting the tools by which law enforcement and private citizens alike were able to trample upon the human rights of the poorest in society.

In 1743, vagrancy offenses were extended to new categories of persons, including those collecting money under pretence and “all persons wandering abroad and lodging in ale houses, barns, out-houses or in the open air, not giving good account of themselves." Offenders were forced into workhouses for up to one month.

Sources

Chambliss, William. "A Sociological Analysis of the Law of Vagrancy."" Social Problems, vol. 12 (1960), pp. 67-77.

Liberty and Power [pseudonym]. "'Enclosure,' Libertarians, & Historians." History News Network, Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, The George Washington University, 19 June 2006, historynewsnetwork.org/blog/26982.

McElroy, Wendy. "The Enclosure Acts and the Industrial Revolution." The Future of Freedom Foundation, 8 March 2012, www.fff.org/explore-freedom/article/enclosure-acts-industrial-revolution/.

"SALC Research Report: No Justice for the Poor: A Preliminary Study of Enforcement of Nuisance-Related Offences in Blantyre, Malawi." Southern Africa Litigation Centre, 24 July 2013, www.southernafricalitigationcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/No-Justice-for-the-Poor-A-Preliminary-Study-of-the-Law-and-Practice-Relating-to-Arrests-for-Nuisance-Related-Offences-in-Blantyre-Malawi.pdf

Stromberg, Joseph. "English Enclosures and Soviet Collectivization: Two Instances of an Anti-Peasant Mode of Development." The Agorist Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 1 ( (Fall 1995), pp. 31-44. Online version by The Molinari Institute, praxeology.net/SEK3-AQ-3.htm.

Torjman, Sherri. Workfare: A Poor Law. The Caledon Institute of Social Policy, February 1996.