Introduction to Existentialism

There are no limitless truths that exist independently of and prior to the individual human being. Existence — our presence in the here-and-now — precedes and takes precedence over any presumed absolute values. The moral and spiritual values that society tries to impose cannot define our existence. Our traditional morality rests on no foundation whose certainty can either be demonstrated by reason or guaranteed by God. There are simply no transcendent absolutes; to think otherwise is to surrender to illusion.

We have feelings and a will.

Reason alone is an inadequate guide to living. We are more than thinking subjects who approach the world through critical analysis. We are also feeling and willing beings, who must participate fully in life and experience directly, actively, and passionately. Only in this way do we live wholly and authentically.

We must act on our thoughts.

Thought must not merely be abstract speculation, but must have a bearing on life; it must be translated into deeds.

what it means to be human?

Human nature is both problematic and paradoxical, not fixed and constant; no person is like any other person. Self-realization comes when we affirm our own uniqueness. We become less than human when we permit our lives to be determined by a mental outlook — a set of rules and values — imposed by others.

The universe is indifferent to our expectations and needs, and death is ever stalking us. This is an elementary fact of existence, and awareness of this fact evokes in us an overwhelming sense of anxiety and depression.

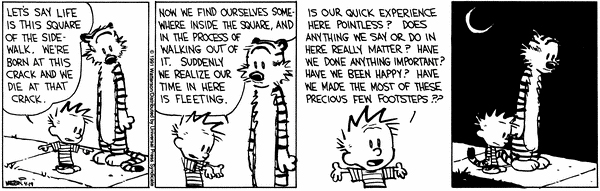

There is no purpose to our presence in the universe. We simply find ourselves here; we do not know and will never find out why. Compared with the eternity of time that preceded our birth and will follow our death, the short duration of our existence seems trivial and inexplicable. And death, which irrevocably terminates our existence, testifies to the ultimate absurdity of life.

Some Basic Distinctions

Morty Sums It Up . . .

And yet . . . we are free to make choices

Mostly from Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics and Society, 7th ed. Perry et. al., 824.

To put it in more philosophical terms:

Most philosophers since Plato have held that the highest ethical good is the same for everyone; insofar as one approaches moral perfection, one resembles other morally perfect individuals. The 19th-century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who was the first writer to call himself "existential," reacted against this tradition by insisting that the highest good for the individual is to find his or her own unique vocation. As he wrote in his journal, "I must find a truth that is true for me . . . the idea for which I can live or die." Other existentialist writers have echoed Kierkegaard's belief that we must choose our own way without the aid of universal, objective standards.

Against the traditional view that moral choice involves an objective judgment of right and wrong, existentialists have argued that no objective, rational, basis can be found for moral decisions. Another 19th-century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, further contended that the individual must decide which situations are to count as moral situations.

All existentialists have followed Kierkegaard in stressing the importance of passionate individual action in deciding questions of both morality and truth. Personal experience and acting on our own convictions are essential for arriving at the truth. Thus, the understanding of a situation by someone involved in that situation is superior to that of a detached, objective observer. This emphasis on the perspective of the individual agent has also made existentialists suspicious of systematic reasoning.

Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Albert Camus (a 20th-century philosopher), and other existentialist writers have been deliberately unsystematic in the exposition of their philosophies, preferring to express themselves in aphorisms, dialogues, parables, and other literary forms. Despite their anti-rationalist position, however, most existentialists aren't irrationalists in the sense of denying all validity to rational thought. They have held that rational clarity is desirable wherever possible, but that the most important questions in life are not accessible to reason or science. Furthermore, they have argued that even science is not as rational as is commonly supposed. Nietzsche, for instance, asserted that the scientific assumption of an orderly universe is for the most part a useful fiction.

Perhaps the most prominent theme in existentialist writing is that of choice. Humanity's primary distinction, in the view of most existentialists, is the freedom to choose. Each human being makes choices that create his or her own nature. In the formulation of the 20th-century philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, existence precedes essence. Choice is therefore central to human existence, and it is inescapable; even the refusal to choose is a choice. Freedom of choice entails commitment and responsibility. Because we are free to choose our own paths, we must accept the risk and responsibility of following our commitment wherever it leads.

Kierkegaard held that we experience not only a fear of specific objects but also a feeling of general apprehension in life, which he called "dread." He interpreted it as a call to each individual to make a commitment to a personally valid way of life. The word "anxiety" (German Angst) has a similarly crucial role in the work of the 20th-century philosopher Martin Heidegger: anxiety leads to our confrontation with nothingness and with the impossibility of finding ultimate justification for the choices we must make. In the philosophy of Sartre, the word "nausea" is used for our recognition of the pure contingency of the universe, and the word "anguish" is used for the recognition of the total freedom of choice that confronts us at every moment.

from http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761555530/Existentialism.html

So what do we do with this condition?

Our consciousness is merely an electrochemical reaction inside a dying chemical reactor called a brain which, out of animalistic instincts to protect itself from pain, creates the illusion of meaning and significance in a reality that has none. Good, evil, morality, and thought are nothing but illusions, with no absolute standard in the universe by which to prove their absolute existence as immutable physical laws.

If we can acknowledge this, we have three choices:

This is the easy way, and, to be honest, the way most people choose. Accept the received wisdom, whether it comes from a book, a preacher, a judge, a professor, or some New-Age healer. It's worked for thousands of years, so why question it now? Of course there's meaning in life, how else could humanity have survived for so long? In fact, we've got great collections of multiple meanings for many lives: The Vedas, the Torah, the Tanakh, the Prophets, the New Testament, the Qur'an, the Book of Mormon, Dianetics, and many others. Our literature collects the matters of most import, and we look to many sources of authority that all tell us how to live.

You are not hindered by considerations about what is "right" and what is "wrong." Such "meaningless, fallacious false dichotomies" are for the simple-minded, not for you. Ideas like these are culturally conditioned, change over time, and are usually mouthed by hypocrites. You're not a sheep; you're a wolf. You choose to have little or no restraint in pursuing your instinctual desires.

Life is short, and we're all going to die, so you might as well start living the way you want. The only thing that cares about you is you, so spend your life getting what you want. Don't let conventional morality get in your way. Don't let what people will think about you hinder your actions. You create meaning for yourself by accumulating good things that will make you happy: money, power, knowledge, admiration, experiences, etc. You "win" when you die having satisfied all your desires. Jean-Paul Sartre sums this up in his play, No Exit: "Hell is other people."

You can choose to be caring, loving, heroic, loving, compassionate, or even just nice. Don't cling to pain. Don't expect happiness. Don't fear loss. Accept reality as it is. Enjoy the good and endure the bad. Don't make a big deal out of anything. Be selfless, and unconditionally kind and just, without ever expecting a reward. We're all going to end up as piles of dust, but it's the same for everyone, if they're brave enough to admit it, so why not help each other through this?

Life is short, we're all gonna die and you can't stop it forever... so why not make each others' lives worthwhile and enjoyable? The only thing that matters is letting people know that you care about them, because whatever someone is, has, or can do doesn't mean anything in the end. You create meaning for yourself by spending yourself for others. Without this service, you know how utterly meaningless, pointless and nonrewarding life is.

Albert Camus writes this in his novel, The Plague: “I have no idea what's awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing.”