Yoshiwara - The Floating World

Because they fall we love them — the cherry blossoms.

In this floating world, does anything endure?”

— Ariwara no Narihira (823 – 880)

Some Background on Edo Society (Japanese Feudalism)

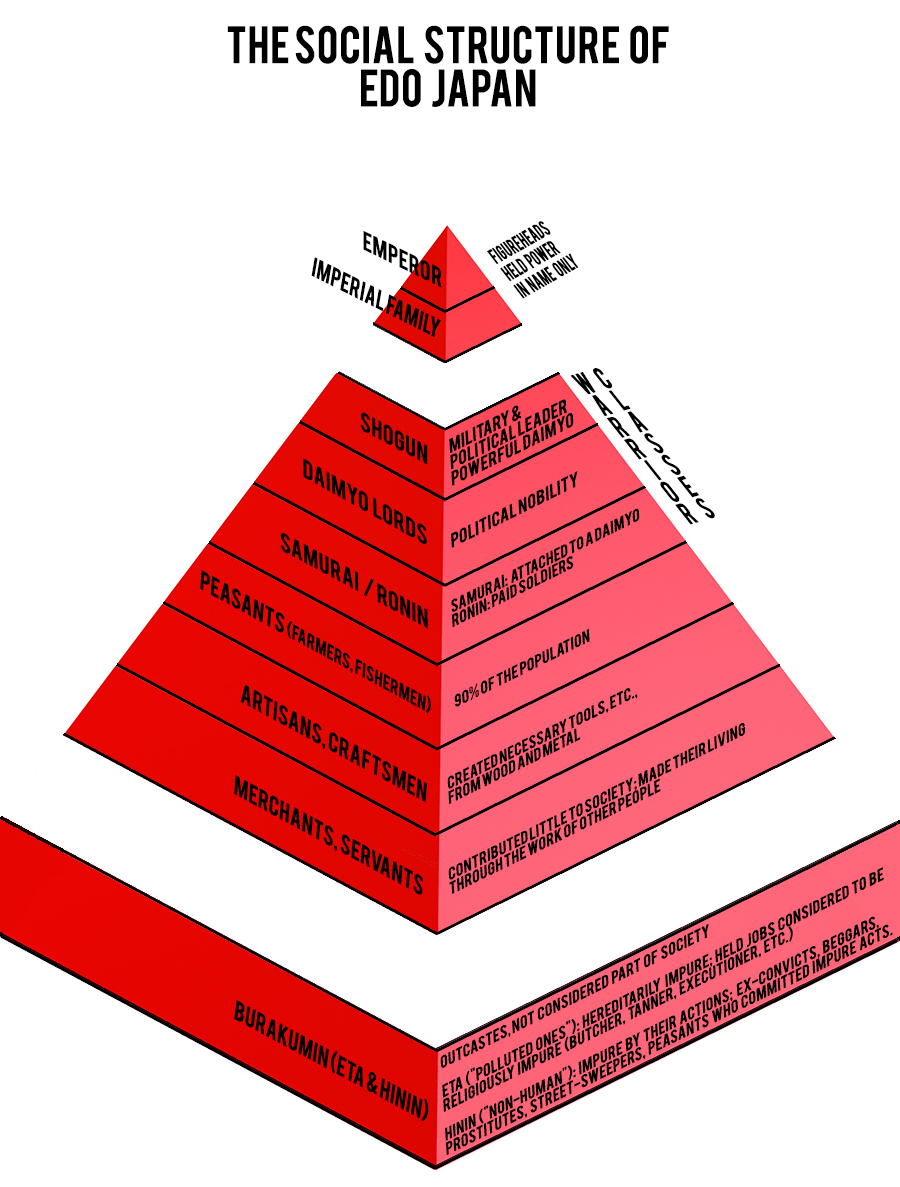

Feudlism during the Middle Ages was not contained to Europe. Between the 12th and 19th centuries, the social structure or class system in Japan was highly elaborate, with several levels. There were four main classes, with other classes considered to be either "above society" or "below society."

This understanding of society was influenced by Neo-Confucianism, which presented a humanistic and rationalistic view of the world. It had several ideas in concert with the European Enlightenment, namely that the universe could be understood through human reason, and that it was up to each person to create a harmonious relationship between themselves and the universe. However, unlike Enlightenment ideals, Neo-Confucianism emphasized the importance of the contributions each class of people offered to society. Thus, to a certain extent, they valued those who were more productive over those who were not productive members of society. At the beginning of the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shōgunate adopted Neo-Confucianism as their guiding principle in controlling both individuals and groups of people. But both Buddhism and Shintoism still had plenty of political clout.

By the time that Tokugawa Ieyasu seized power for himself and his descendants in 1600, and established a Shōgunate government at Edo, the Emperor, the Imperial family, and all the court nobility held no real power; the Shōgunate held the real military and political power. That power relationship would remain in place until 1867, when the last Shōgun of the Tokugawa clan resigned, ceding his military and political power to the Emperor.

The Four Tiers

Above the Four Tiers: The Emperor

The emperor, his family, and the court nobility are shown as "above society" in the image below, because they were at least nominally above the shogun, and also above the four-tier system. The emperor served as a figurehead for the shogun, and as the religious leader of Japan. Buddhist and Shinto priests and monks were above the four-tier system, as well.

Tier 1: The Warriors

For over two centuries, the warrior class—the Shōgun of the Tokugawa clan, the Daimyō lords, and their retainers, the Samurai—administered Japan through their system of domains. The polite fiction was that the Shōguns ruled in the name of the Emperor, but in reality they held all the military power and most of the political power throughout the Edo period. The warrior class made up about 10% of the population of Japan. Consider that North Korea—considered to be the most militarized society on earth today—had in 2023 less than 5% of its population serving in its military, which is less than half of the numbers in the Edo warrior classes, and you get an idea of just how built up the Japanese war machine was during the Edo period. At the end of the Shōgunate, there were about 260 Daimyō lords dividing all of Japan between themselves.Tier 2: The Peasants

Most members of Edo society, about 90% of them, were commoners. The highest of these was the peasant class, who were the farmers and fishermen. According to Confucian ideals, these people were superior to artisans and merchants because they produced the food that all the other classes depended upon.Tier 3: The Craftsmen

Then came the craftsmen and artisans, those who created useful things for society. They manipulated raw materials into beautiful and necessary goods, such as clothes, cooking utensils, swords, and even boats.Tier 4: The Merchants

The lowest was the merchant class (which also included household servants), because they didn't actually produce anything, but made their livings by brokering the work of others. Merchants were ostracized as "parasites" who profited from the labor of the more productive peasant and artisan classes. Not only did merchants live in a separate section of each city, but the higher classes were forbidden to mix with them except on business. Nonetheless, many merchant families were able to amass large fortunes. As their economic power grew, the restrictions against them weakened.

Below the Four Tiers: The Untouchables

Feudal Japan also had its own "untouchables," people whose ancestry, occupations, or life choices placed them "below society." This classification is pretty fluid, but in general the Burakumin either held hereditary positions that made them "impure" (Eta), or were "impure" because they chose a life that put them at odds with the rest of society, like prostitutes, beggars, or ex-criminals (Hinin).

Yoshiwara - The Floating World

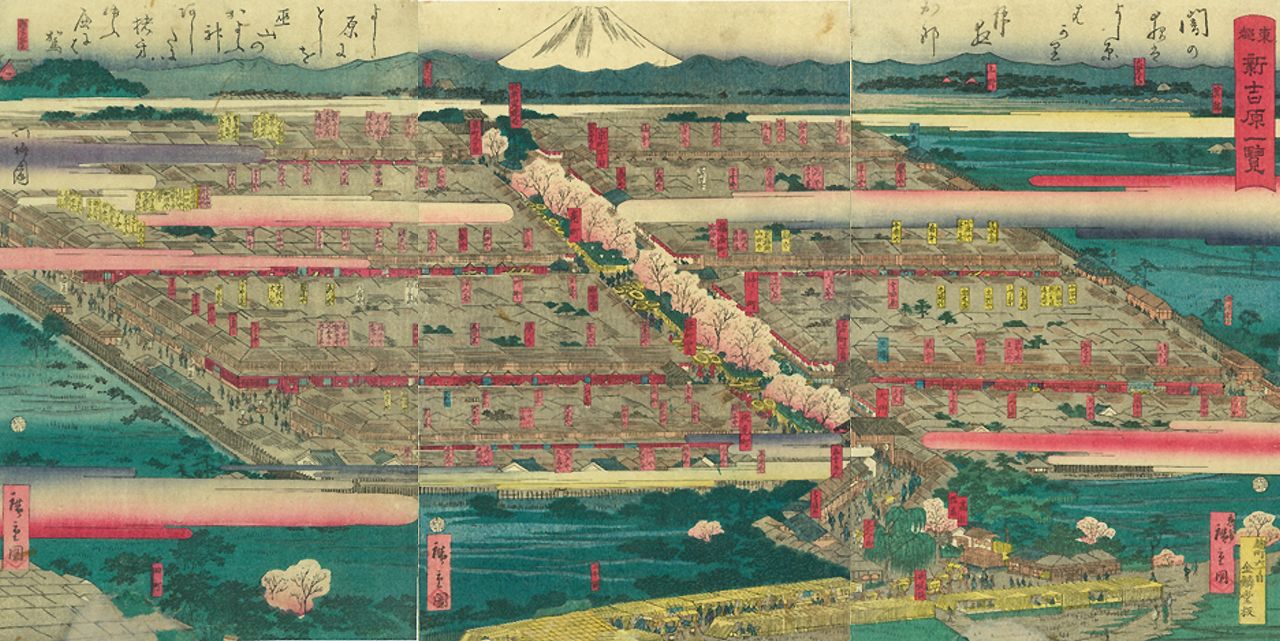

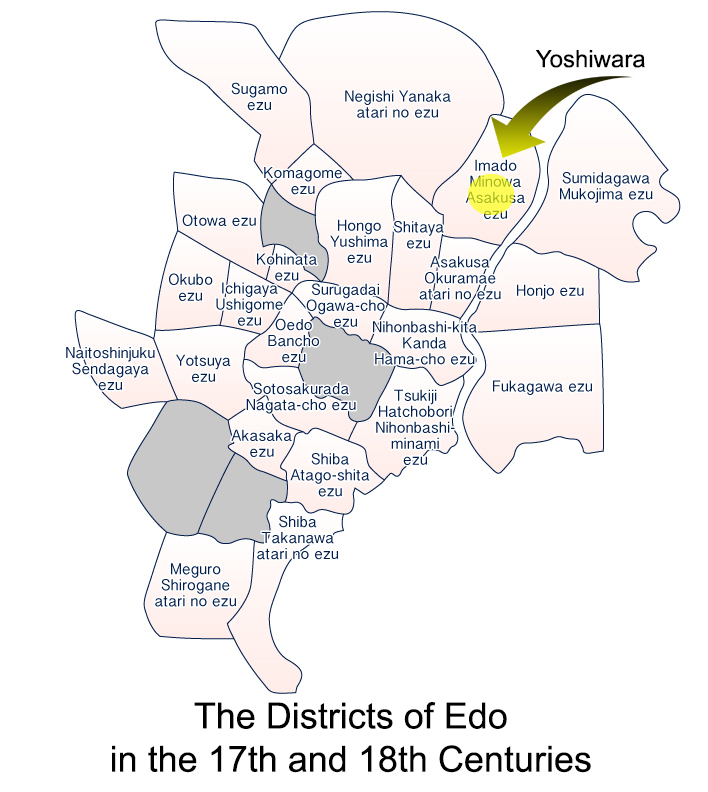

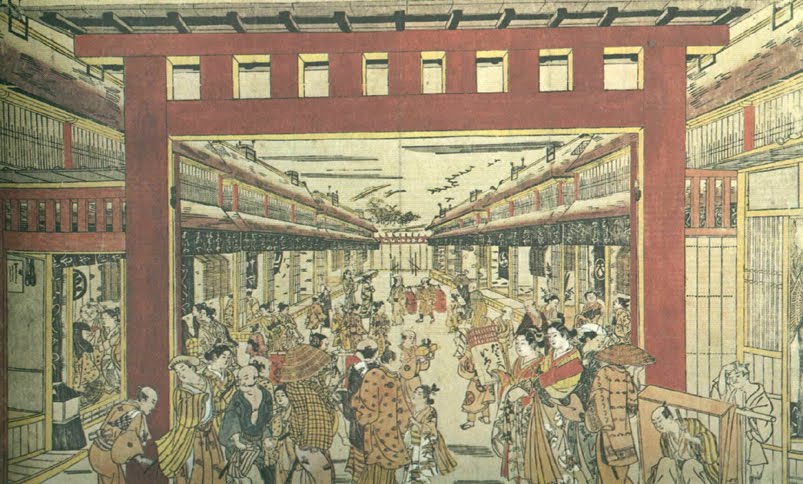

The Yoshiwara district was around 300 yards by 400 yards, surrounded by a moat, and generally only accessible by a large central gate.

The Nakanochō main street, lined with cherry trees, had teahouses that mediated for the brothels.

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

By the end of the 17th century, the Shōgun Hideyoshi was faced with a unique problem: the four tiers of society were being upset by a rising merchant class, gaining more and more wealth, with both time and money on their hands. If they became restless or bored, they might question the order, or indeed the very existence, of Japanese society. In the old world of serfs and lords, this had not been a problem.

In Edo (later called Tokyo), the capital city of Japan, the Shōgun thought he might find an answer. Almost every district in the city was littered with sex clubs, vulgar theatrical shows and other entertainments, and both male and female prostitutes. Sex was hot, and the local priests were not happy.

So Hideyoshi decided to conslidate all this vice in one spot. He took a large tract of land north of the city—accessible only by canal, which was called "Good Luck Meadow," or, in Japanese—Yoshiwara. He had the remainder of the tract enclosed by a moat, so that the only access was by water. This was done to keep minors and criminals out (and the sex workers in). Visitors got the impression that the whole area was an island, and called it "The Floating World". The term applied not only to the geography of the place, but to the floating feeling one has when in the throes of sexual satisfaction.

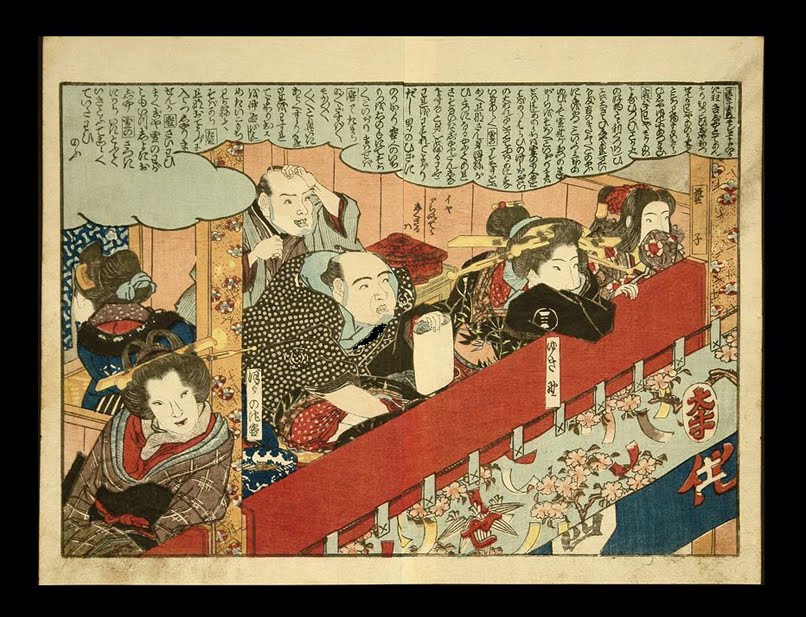

The area soon filled with brothels, teahouses, Kabuki theaters, Sumo arenas, and other forms of entertainment. New York may be "the city that never sleeps," but this district in Tokyo had that nickname first. Yoshiwara was known as "The Nightless City" when New York was still a little fishing village.

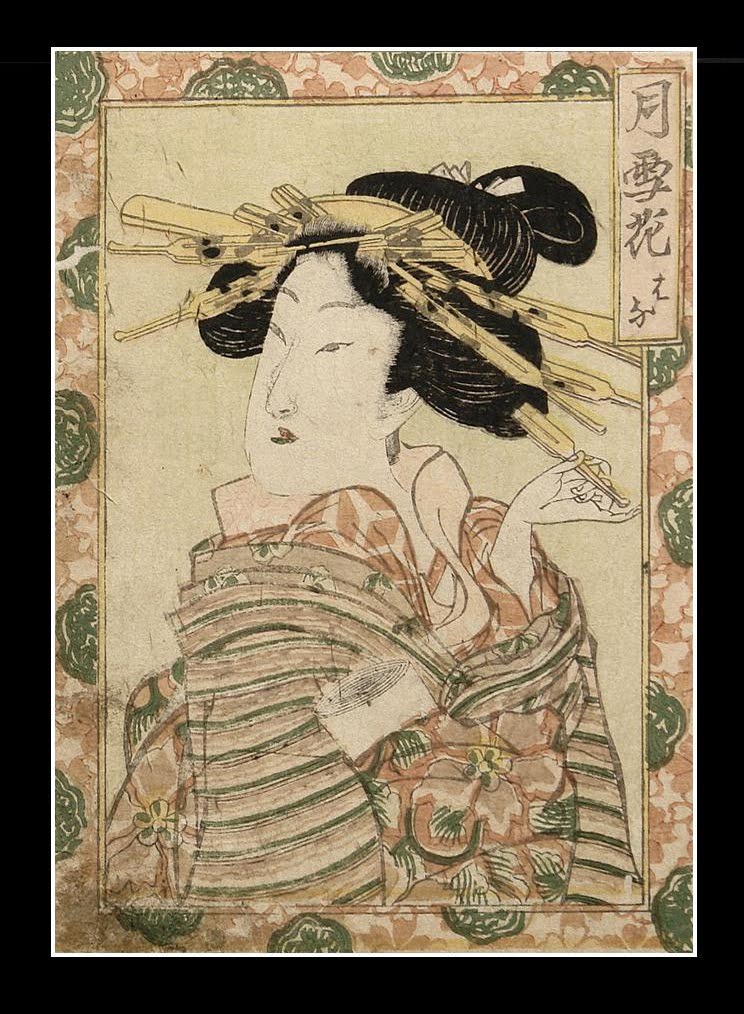

However, this was no typical "Red Light" district. Inside the Yoshiwara, unlike the rest of Japan, there were no class or gender distinctions. Samurai were technically forbidden from the Yoshiwara, so they had no authority there. The floating world had its own rules. A farmer (assuming he had the money) was treated the same as a Daimyō. Women were not only allowed, but encouraged, to learn to read and write, study music, the arts and history. They were also allowed to run their own businesses. Some became very wealthy and had their own "concubines."

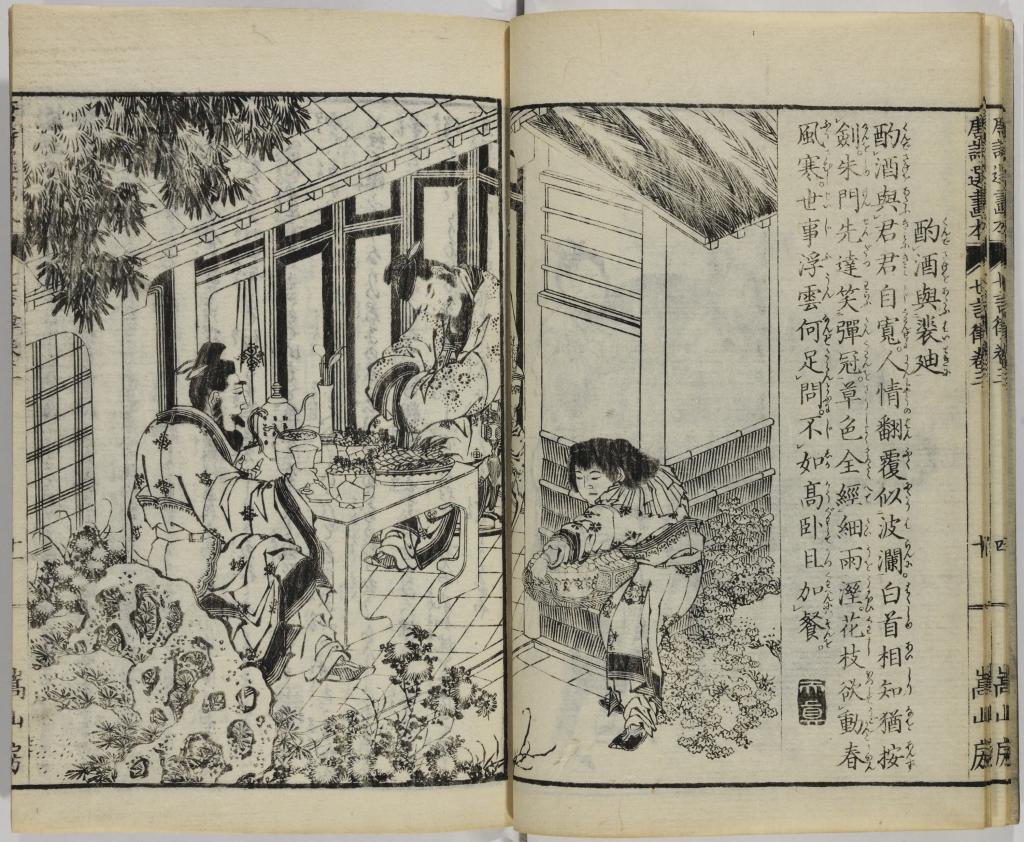

People involved in Mizu-shōbai ("the water trade") included kabuki actors (popular theatre of the time), dancers, dandies, rakes, tea-shop girls, Kano (painters of the official school of painting), Hōkan (male entertainers), yujo (ordinary prostitutes), courtesans who resided in seiro (green houses) and geisha in their okiya houses. Homosexuality, cross-dressing, and fantasy role-playing were all widely tolerated.

Also for the first time, sex and sexuality were treated openly and freely. You could seek out any fantasy you chose, without fear of reproach. Classes were taught in sexual technique and were well-attended. Safety became a concern (accidents were bad for business). Shibari and Kinbaku (sexual bondage) became art forms. Inside "the floating world" you could be whatever you chose to be, if you were smart enough and worked hard enough to achieve it.

Compared to the rest of Edo, or indeed the rest of the country, Yoshiwara was a model for a new type of society, the only place in the nation where where you were not limited by your birth, where women and men were treated equally, and where you could advance in social status and standing. There was a level playing field for anyone who entered, and all were treated equally, no matter their position in the outside world.

Author: Takai Ranzan | Artist: Katsushika Hokusai

The Rise of Realism

Before the 1620s, the only books available in Japan were handwritten manuscripts. And all the monogatari, tanka, renga, and haiku (the great Japanese classical forms) were disseminated through these manuscripts. But a new type of book, printed with woodblocks, became popular in the 17th century. The printed kanazõshi were less expensive and more widely available than these earlier manuscripts. They are really the first commercial literature produced in Japan.

Saikaku became one of the most popular writers of his time because he wrote this type of book, focusing specifically on the Floating World. But "popularity" is a relative term. Books were still very expensive — costling roughly what a laborer earned for two or three days of work. Also, these books, because of their small print runs (often only a few hundred copies), did not often circulate beyond the major cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo, which were the publishing centers in pre-modern Japan.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, these books amounted to an important new trend in literary production. Closely tied to the rise of Japan's urban centers, the growing economic power of the chõnin (urban commoner) class, the improvement of literacy rates, and the advent of woodblock print technology, kanazõshi (and ukiyozoöshi, the kanazõshi particularly about the Floating World) emerged as a new, distinctly lower- and middle-class form of literature.

While the authors of this new type of literature came from the educated portion of the population (including scholars, Buddhist priests, courtiers, samurai and ronin), the readers were mostly the non-aristocratic residents of Japan's growing cities.

In contrast to the classical and medieval literature which preceded them, kanazõshi tended to be more realistic, with fewer supernatural or fantastic elements. They paid more attention to details about the characters and their setting, contained more natural dialogue, and showcased a more representative slice of life.

A Street Scene in Yoshiwara

Upper-Class Audience Members at the Kabuki Theater

Courtesans Entertaining Their Clients

A Geisha in the Fashion of the Day