History of Science Fiction Part I

Anthony Gramuglia

When chronicling the history of science fiction, you need to think about the history of SF as it pertains to the history of mankind. Throughout its span, SF asks where we are as a species, where we will go, and what will happen when we get there.

Humanity has asked these questions since the dawn of civilization, but it wasn't until the 19th century that we realized that we had the technology to do great things — to expand beyond the limits of humanity.

It has fallen upon my shoulders to chronicle the legacy of science fiction — from the science fiction novels of Mary Shelley and H.G. Wells, to the adventures of Buck Rogers and John Carter, to the voyages of the USS Enterprise and Millennium Falcon — to now. The history of science fiction is vast and complicated, and, should you understand this, you understand not just the imagined technologies of years gone past, but an understanding of humanity today and tomorrow.

medieval texts that could be called Science Fiction.

Proto-Science Fiction

The history of science fiction truly begins before science fiction as a genre really started to take shape. Many old texts depict scenarios where man traverses beyond the limits of the world, and dives into space and the cosmos beyond.

Even before the Renaissance, it is clear that humanity looked to the stars, and asked "Are we alone?"

Greek writer Lucian wrote True History, which depicts a man who travels beyond the heavens to witness a battle between the People of the Moon and the People of the Sun. The Japanese story, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, depicts a princess named Kaguya who descends from the moon to Earth, only to ascend back to join her people later on.

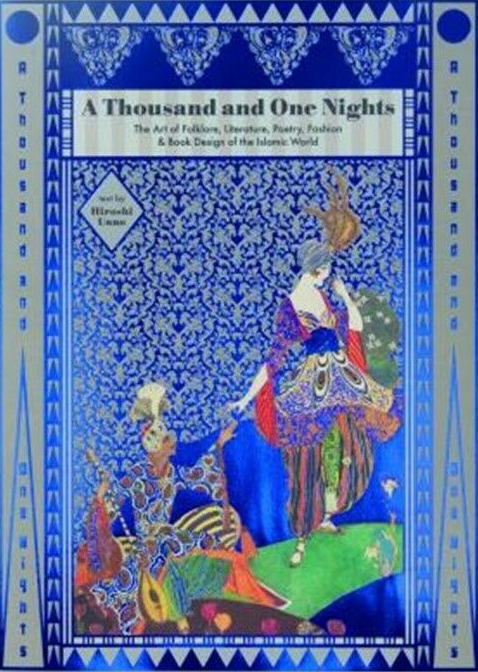

One Thousand and One Nights features many images that feel like they sprang straight out of a science fiction story. The story "The Ebony Horse" depicts a man-made horse that, with the turn of a key, can carry a cart beyond the atmosphere into the outer reaches of space.

Another story, "The City of Brass," depicts an ancient city built near a machine that King Solomon used to capture djinn. The city, comprised of abandoned technology, is filled with living puppets without puppeteers and other constructed men — or automatons.

However, these old stories do not credit science for these miracles. Rather, the books and stories depict these machines and aliens as magic and enchantments. Man creating another man with gears and parts — why, that was a product of alchemy and magic.

Consider Dante's The Divine Comedy. In this trilogy of epic poems, Dante dives into the Hell, located beneath the Earth's crust, only to emerge on the opposite side of the planet, climb the mountain of Purgatory, only to ascend to the Heavenly Spheres — each planet in the sky consisting of the souls of Heaven.

While much of the iconography when removed from the religious context resembles the sort of stuff Jules Verne and H.G. Wells would later write about, the explanation for space and the composition of the Earth's core is religious in nature. Not scientific.

It wasn't until the Age of Reason that the first science fiction stories started emerging.

saw that science influence and imbue its literature.

The Age of Reason

In the decades following the Italian Renaissance, Europeans believed that they had transcended to a new level of human understanding, and, for the first time, were capable of addressing issues of science. Galileo and Copernicus were publishing their theories about the nature of the cosmos, and Leonardo da Vinci had already designed early, clockwork designs of the helicopter. Science fact had become in vogue.

Which led many to ask "What comes next?" After all, they now, for the first time in human history, knew of the colossal structures beyond the clouds. How long before they could get there?

The earliest of science fiction began to emerge at this time. The history of science fiction begins.

The two earliest examples of science fiction are Johannes Kepler's Somnium (1634) and Francis Godwin's The Man in the Moone (1638).

Both books depict protagonists traveling to the moon. Somnium is the more religiously inspired of the two, with a boy being drawn to the moon — an island in the sky known as Levania — by a daemon.

Godwin's science fiction novel, however, is an adventure novel where a character adventures into the depths of space, coming across insane, intense sights along the way.

Many adventure stories, inspired by the voyages to the New World, saw the potential of unique civilizations living beyond the sky. Often, science was described in abstract ways. Space typically was described as being full of aether or air, which, to a modern perspective, comes across as a little bizarre.

Adventure seems to be a reoccurring theme in early science fiction. In Margaret Cavendish's The Blazing-World (1666), an adventurer witnesses a new world located on the North Pole — a civilization that has warded off the ice and cold.

Simon Tyssot de Patot's La Vie, Les Aventures et Le Voyage de Groenland du Révérend Père Cordelier Pierre de Mésange (1720) is an adventure that dives into a Hollow Earth beneath our feet.

Once again, science here is applied loosely, and the spirit of adventure predominantly rules.

Paradise Lost, which he takes as a true history,

since he can't distinguish between imagination and reality.

The Modern Prometheus

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is often regarded as a gothic horror novel. And it is. However, it's an important entry in the history of science fiction, as it is one of the first stories to truly break the mold of the then-traditional science fiction novel.

Before, stories had focused on science as a means of adventure, to go to some place — any place — liberated from the conformities of the world. Most writers didn't bring science down to Earth, but used science to get away from the mundanity.

But leave it to a young girl, one Mary Shelley, the wife of famed poet Percy Shelley, to approach one of the big questions: what negative consequences await us if science continues to advance? Will we entreat on God's domain to create life? And, if so, what are the consequences?

Frankenstein is the first of many unions between horror and science fiction.

As you know, the story tells the tale of Victor Frankenstein, a man who strove to create life from nothing. He creates a creature who he abandons after creating it, leading to the creation to resent the creator.

For its time, this story broke ground by questioning the consequences of scientific advancement. In many ways, it became the forerunner of countless stories to follow where technology and scientific advancements spiral out of mankind's control.

But the history of science fiction is not merely one told in landmark narratives. Other writers tried to capitalize on the Frankenstein craze. Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827) tells the story of an Egyptian mummy resurrected in the year 2126 thanks to advanced scientific technology — only, unlike Frankenstein's Monster, the mummy is pretty chill with coming back, and only wants to make the world a better place.

behind only Disney Productions and Agatha Christie.

Jules Verne

From here, the science fiction genre seemed to divide in two. Some SF became focused on depicting science as a means for adventure and new experiences, while other stories focused on the negative implications of scientific advancement and scientific understanding.

Jules Verne liked adventure.

Jules Verne essentially wrote light science fiction in serialized form, with the science serving as justification for new and exciting worlds to explore. The following dates included are when the stories started serialization, not their reprinting in complete volumes.

Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) depicts a group of adventurers diving below the surface of the world to find a whole new land full of prehistoric creatures and fauna. While many stories depicting a Hollow Earth predate Journey to the Center of the Earth (such as Simon Tyssot de Patot), Verne popularized the genre with this story, and, from there, numerous knock-offs began to emerge in both novel length stories and short fiction.

Verne, not content with altering the history of science fiction with one novel, kept going. The Hollow Earth offered plenty of adventuring potential, but Verne chose to adventure space next with From the Earth to the Moon (1865), which suggested that man could travel through space to the moon by firing a bullet from a super-sized gun.

Again, work had already depicted man traveling from Earth to the moon before, but no writer in the history of science fiction before Jules Verne tried to calculate how fast the bullet would have to fly, where the vessel traveling to the moon would have to launch from, or any of those more scientific details.

While any science fiction writer could throw numbers and jargon at a page, Verne's calculations on how one could launch a ship to the moon, when compared to the eventual Apollo 11 space launch, proved (mostly) accurate. While From the Earth to the Moon may not be one of Verne's more beloved works, it remains proof that Verne wasn't just another adventure writer. He was a true science fiction writer.

Verne's most famous novel remains 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: The Original Classic (1869). Verne's Captain Nemo pilots a submarine known as the Nautilus. While submarines did exist in some primitive manner, the Nautilus was far more advanced. It established a future precedent most SF would draw from: take an existing piece of tech, and make it more advanced using scientific possibility.

Verne's writing strongly resembles the modern genre of "steampunk," as both steampunk and Verne took 19th century technology, and imagined how the tech existing at that time could be used to go on fabulous adventures.

What many modern readers need to remember is that steampunk writers return to the 19th century as a source of nostalgia. Verne lived in that era. He took what he saw around him, applied some math, and created something wholly unlike anything the world had ever seen before.

in far-flung places that shared the thrill of scientific discovery,

technological innovation, and colonial exploration to a pre-film society."

Scientific Romances

It is no exaggeration to call Jules Verne the first science fiction writer. Mary Shelley might have written the first great science fiction novel, but Verne pumped out these stories, influencing the genre forevermore. He is a vital point in the history of science fiction.

Followers of Verne wrote what many at the time referred to as "scientific romances." Verne, however, cannot be credited as the sole founder of the genre of scientific romances. Another major work that helped formulate the genre was Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation by Robert Chambers, written in 1844 (a full two decades before Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth). The story attempted to present a history of humankind based on speculation and then-current theory.

Much of the scientific romance stories established popular themes that, in later years, would become cliches and tropes of the science fiction genre. Every one of these stories holds a special place in the history of science fiction.

In William Henry Rhodes' The Case of Summerfield (1870), a mad scientist designs a killer death ray that has to be stopped.

Edward Page Mitchell, from 1874 onward, published numerous short stories in the American newspaper The Sun, which depicted several stories of invisibility, mutants, and faster-than-light travel.

Numerous American writers wrote stories of "automatons," or machine people constructed by scientists. Most of these pulp stories combined the influences of Mary Shelley and Jules Verne in order to create a narrative of its own derivative style. Most notable of these is The Steam Man of the Prairies (1868) by Edward S. Ellis.

Even popular writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the same man behind the classic Sherlock Holmes stories, would end up joining in years later with the story The Lost World (1912), which depicted an island separate from the rest of the world where dinosaurs still roamed.

But all were overshadowed by the rise of one of science fiction's greatest writers, one who, upon publication, changed the history of science fiction forever.

space travel, the atomic bomb, satellite television and the worldwide web.

H.G. Wells

It is not up for debate that H.G. Wells is one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time. It is a fact.

While most writers of his time approached science fiction with a sense of wonder and excitement, Wells chose to approach science with a slightly more cynical approach, one that saw the inherent dangers of the future and of science speculation. While Verne wrote of adventures beneath the earth and sea, Wells saw something less hopeful.

In 1895, Wells published his first science fiction novel, The Time Machine. In it, a man develops a machine to travel through the dimension of time without ever moving location.

He discovers that, by the year 802,701, mankind has evolved into two separate species: the peaceful, defenseless Eloi and the violent Morlocks. While the novel is a political satire, it also incorporated numerous new scientific theories of Wells's day, such as Darwin's Theory of Evolution and the concept of time as a dimension-like distance.

In a disturbing moment, the Time Traveler travels to the ends of the Earth, watching the planet become progressively more and more alien until the world itself begins to die.

You have to remember: while time travel had been alluded to in fiction before (usually in the form of seeing the future), never had anyone constructed a machine that could travel through time. Nor had any story depicted the end of the world in a scientific, non-religious manner.

Wells would again reshape the history of science fiction with his later novel, The War of the Worlds (1898). While stories had depicted creatures living on alien worlds before, this is the first one that depicted aliens as a race who wanted to invade and colonize Earth. Mankind is powerless to stop the aliens, who possess far more advanced technology than any of them. Which makes their eventual defeat thanks to bacteria even more stunning (this twist would inspire numerous later works of science fiction, most notably to modern audiences Independence Day and Signs).

But The War of the Worlds is not merely an alien invasion story. It is also Wells's criticism of British imperialism. Wells figured "Well, the British go in and invade other lands with inferior technology? How would we feel if someone tried the same thing on us?"

Again, Wells is successful not merely because he was the first. Wells wasn't. H.G. Wells is among the greatest science fiction writers of all time because he was the first to do this sort of stuff well. And not only well, but extraordinarily well. He infused science fiction with social commentary — something that only the most successful works in the history of science fiction managed to pull off well.

Wells's approach to writing, however, does have flaws. Flaws that are made more interesting when contrasted with Verne's flaws. Jules Verne used math and science to explain what happened, but his focus was first and foremost on adventure and thrills and characters. Wells, however, focused on ideas and science, but his characters are very underwhelming. One of the core reasons The War of the Worlds has yet to have a truly great film adaptation is because the main character is a passive player in the plot, observing the invasion rather than doing anything active in the plot.

For the rest of our history, please consider this debate: what is more important in works of science fiction? The science — facts, details, and the like — or the fiction — the characters, the plot, and the thrills?

After Wells, the history of science fiction launched into overdrive. In the next part of our series, we will focus on the era of pulp magazines, the rise of Edgar Rice Burroughs and H.P. Lovecraft, the 50s science fiction boom, and the Big Three writers of science fiction.