The Medieval Universe

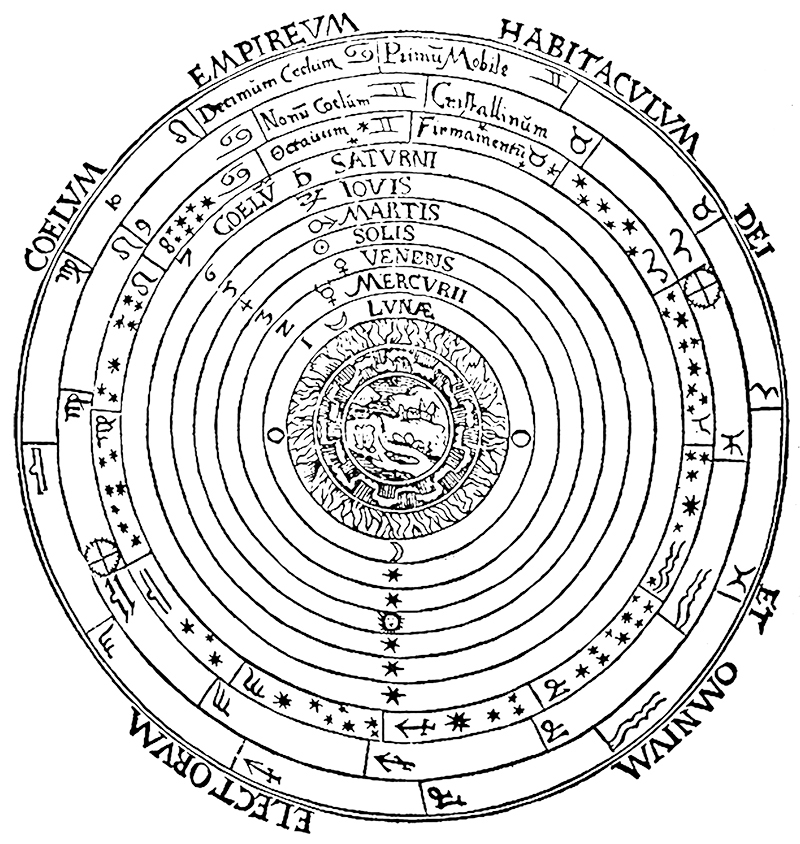

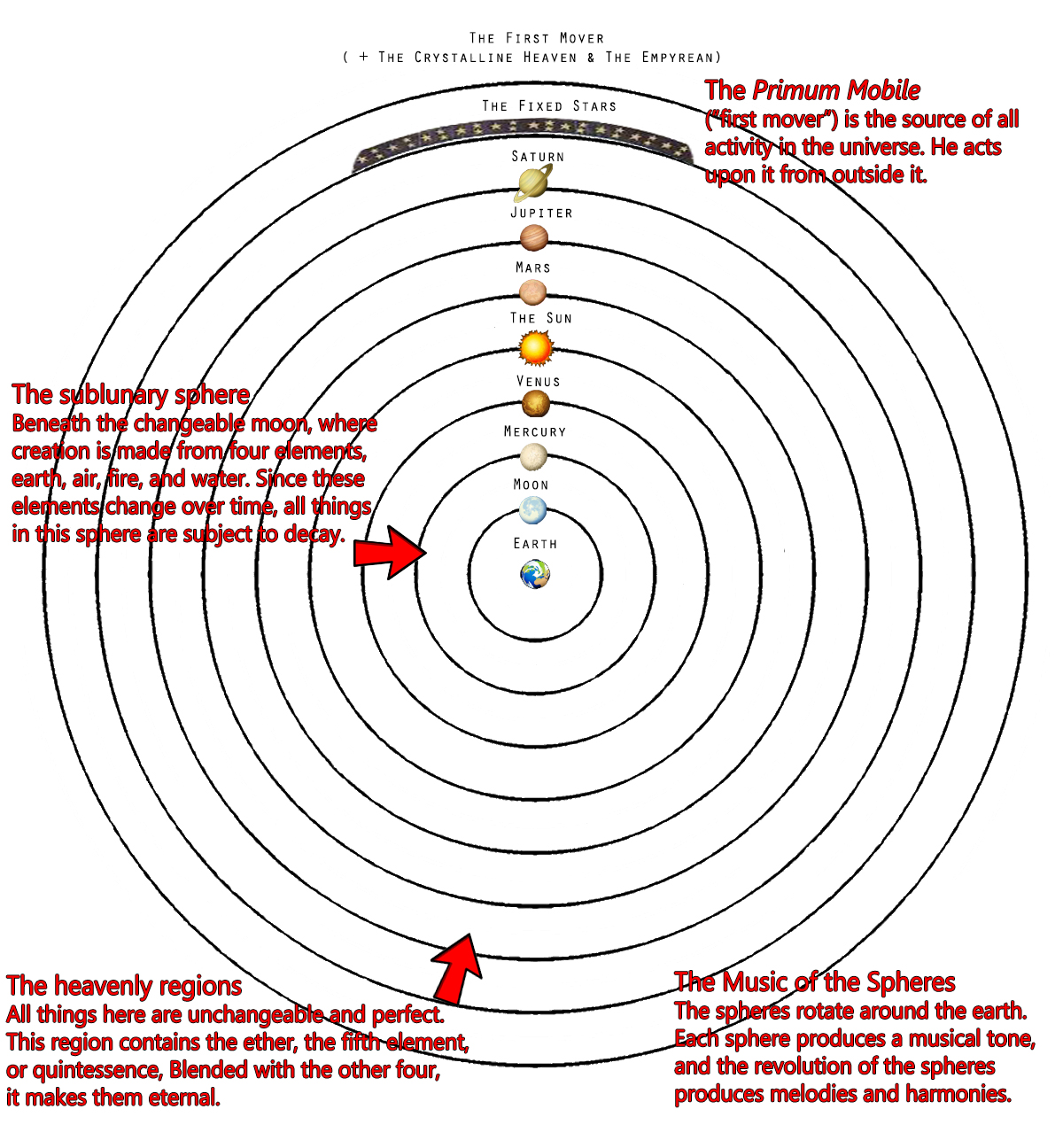

In this geocentric (earth-centered) model, the Earth was the motionless center of the universe, with the rest of the universe revolving around it in perfect spheres. Ptolemy's work was based on Aristotle's (384-322 BCE) idea of an ordered universe, divided into the sublunary, or earthly, region—which was changeable and corruptible—and the heavenly region—which was immutable and perfect. Aristotle posited that the heavens contained 55 spheres, with the outermost sphere, the Primum Mobile ("Prime Mover" or "First Moveable") giving motion to all the spheres within it.

Closest to the Earth, and therefore the most influential, was the Moon. Thus the first sphere of influence on the Earth was the sublunary sphere (sub=below; lunar=moon). Everything that existed within this sphere was made up of the four elements (earth, water, fire, and air). The Mon itself is ever-chaning in the night sky, so its influence had to do with mutability, or impermanence. Beyond the Moon were the spheres of the Sun and the planets. After these came the Circle of the Fixed Stars (including the signs of the Zodiac). Outermost in this scheme was the Primum Mobile, sometimes divided into three spheres of the Crystalline Heaven, the First Moveable, and the Empyrean, or highest heaven.

This aether was the fifth element, or quintessence. It was incorruptible and unchangeable. But it did not exist in the sublunary sphere (that is, on Earth). Therefore, everything on Earth was changeable, but everything above the Moon was permanent. These spherical shells made of aether fit tightly around each other, without any spaces between them. Each sphere had its particular rotation that accounted for the motion of the heavenly body contained in it. Outside the sphere of the fixed stars, the Prime Mover (himself unmoved), imparted motion from the outside inward. All motions in the cosmos came ultimately from this Prime Mover. The natural motions of heavenly bodies and their spheres were perfectly circular, neither speeding up nor slowing down.

The Prime Mover became the Christian God, the outermost sphere became heaven, and the earth was the center of God's attention. The spheres, moved by the Prime Mover, existed and rotated in perfect harmony, creating the “music of the spheres.” Humans, who lived in the sublunary sphere (which was corruptible since Adam's fall), could no longer hear this music. This worldview gave rise to further Medieval philosophical explanations of humanity's place in the universe, such as the concept of corresponding planes, and the idea of the Great Chain of Being.