Poetry

for Mary McGervey

It must begin slowly, haltingly,

With a long pause between —

The second and third notes,

Before the swirling cascade,

Spinning faster and faster

As it comes under her fingers.

And I must hear the fingernails,

Clicking a touch before the string sounds,

Like a doorman holding time for the guest.

What I hear on disc is too perfect;

It carries a polish and finesse,

But there is nothing of the student,

Nothing of the struggle,

Of the fight to get it

In your fingers and you out of the way,

So Chopin can come through.

I want to hear the work,

The mutterings, the lost threads,

The faltering fingers

That say, “I am still here,

Still trying to become transparent,

But I am too solid.

You cannot see through me;

You can only see my hair as it falls down my back,

And the smile on my face as I turn to watch you

Watching me make Chopin.”

No descending doves, announcing virgin births or beloved sons;

No kingfishers catching fire or dispersed swallows twittering;

No swan, no nightingale, no albatross –

Even the wild geese no longer call to us.

This is how the world speaks now, a sudden clutch

At the chest, a left arm gone numb, the chirping

Of the pulse-ox monitor. Or the slow circling

Of disease, waiting for the carrion, whispering,

As the birds did,

“You are called, you are chosen.”

Able

Babble

Cable

Dabble

Easy

Feeling

Greasy

Healing

Into

Jumpy

Kin to

Lumpy

Moldy

Nosing

Oldy

Posing

Quicken

Roaster

Sicken

Toaster

Under

Vino

Wonder

Xeno

Yawning

Zero

Awning

Biro

After the truck has been packed,

The pizza eaten, the beer drunk,

There is that awkward moment, when all know

It is time to go, but no one has yet moved.

Then we tumble toward farewells,

Hurried hugs and promises,

Bluff predictions of return.

Next the mounting of the truck’s cab,

The engagement of gears, and one last mirrored look at

Friends, closer than they appear.

Finally, the metronome of one arm,

Waving goodbye,

Ticking away the seconds of silence and regret.

Eyes like a fermata, holding your gaze.

Voice like an oboe from Bach.

Touch that raised melodies.

Softness that whispered pianissimo.

Yes, I remember you and your music.

Good writers work

Out of habit and custom.

Participating in all that Hume

Said gave us cause and effect.

But good poems come

From something unknowable.

Proving Hume’s null guarantee

That our future will resemble our past.

I want to be the man

Who stands when soldiers enter the room, salutes

Veterans and buys them dinners, nods

At uniforms, genuflects

In front of the wounded.

I want to be the man

Who claps for the troops,

Tears up at the national anthem, respects

The blood sacrifices,

And understands the cost of freedom.

Yet when I do, I am called back

To a kitchen table and a daily fight:

Mother of a draft-age boy versus

Korean War vet,

With my future as the prize.

I see the eyes of yellow, brown, white men

Going dim, as memories of wives and mothers fade.

I see fat men feasting on the blood sausage of the poor,

Committing others’ children to die in their stead.

So now I am neither protester nor apologist,

Having worked out my own armistice.

Here we go again. The places change,

The faces refresh, but the form is always the same:

Earnest apostles bringing our own good news to

An audience of peers—

“It’s either this or another paper on Milton.”

The readers of the same ilk:

Soulless men protesting too much.

Dicked-over women complaining.

Earnest grad students writing “fuck”

To make a statement.

The listeners, attentive,

Sympathetic clucking and nodding of heads.

“Yes, she’s been on this sequence for a while.”

“No, he’s still shopping his manuscript.”

Supportive, letting everyone know, “I was there at the beginning.”

But then there’s the whispering behind hands,

The sideways talking: “It’s not quite her best work.”

“I enjoyed his earlier stuff much more.”

“He seems so distant lately.”

And the genesis becomes an exodus.

At the end, books appear out of purses and bags,

Money embarrassingly exchanged,

Condolences and assurances passed from one to another.

Playing Doctor with our words:

“I’ll buy yours if you’ll buy mine.”

We wouldn’t dare scrub up

To remove an appendix, not without years of training.

But everyone thinks they can do this, can stand here

And unpack their organs, open head, open heart,

Surgeons of the sensate.

I once played Folk City in the East Village,

A rube from the Midwest, not part of the circuit players

Who put in their names, got their stage times,

Dashed to a drawing in another club.

I was never that smart.

I was the dumb one in the audience, with my single shot,

Drinking flat beer and worrying ‘til my ten minutes with the mike,

When the audience was just those who had times after mine,

Listening so they would be listened to.

Now I wonder, “Are you all on after me?”

for my mother

I can still hear the click of her long fingernails

Prefacing each note,

Setting up the sound that will follow.

Her suffering back sighing beside me

As she sits there trying to teach

The rudiments of magic.

Later, I call her from the kitchen

To pick out something, a simple melody,

With too many accidentals.

Again there’s the click of the nail

On the keys of the Everett upright,

There in the living room.

A short snap, then the roundness

As the tone blossoms to fill the space

Underneath the print of Señora Sabasa Garcia.

Sometimes, if she doesn’t press hard enough,

There’s only the click,

Like a snub-nosed hammer on an empty chamber.

She’ll strike again, but with the pad this time

And the note will bloom like blood in water

Its starting gun lost, all fat sound.

But somehow incomplete,

Because it is missing her, the woman

Who makes the music.

I

I was usually awakened by the smells

Of shower, sweat, and ‘Lectric Shave.

All flooding from the bathroom

To the room we shared, my brother and me.

Dad was going to work, and I had to spy.

About four o’clock, every morning,

He’d trudge to the bathroom to get ready.

I might hear the alarm or the shower,

But it was always the smell that pulled me

By my nostrils, awake to the dark morning.

I’d listen to him dressing, careful

Not to wake us, trying to be quiet,

But not quite succeeding. He’d grab his uniform

And his big Russian hat, and I’d wait for his creaky knees

On the steps downstairs, then make my move.

The cellar light would click on loudly,

And one more flight would get him to the garage.

Then the door, the car, and,

If it had snowed, the slow shoveling of two tracks

Up to Methyl Street.

That part I liked best; I could look

From the corner of my window,

Peer down and see him push the snow, careful

To duck in when he turned back to the garage. Peeping

Again to see the second track carved.

Then the car would back up the driveway;

The most dangerous time,

Because the headlights would swing

Across the front of the house. And

Looking up, he might see me seeing him.

I’d watch until the car, first Fairlane, then Ventura, Nova, Buick,

Climbed up Sebring to the world of work.

He hated this job, but had responsibilities, and with these

Came the chores of every morning.

Bad knees don’t make good mailmen.

II

One morning I was caught short:

Do I stay and watch, or hit the bathroom

And miss his leaving?

I stayed.

One knee on the cold hassock,

One foot on the floor,

One eye between the curtains,

I felt the piss run down my leg,

Plastering my pajamas to me.

I watched him pull out of the garage

And drive into the darkness.

Past the street football endzone,

Past the baseball second base,

Past all the scars that city paving would erase.

When they finally sold that house,

Years after I moved away,

That mark was there still,

Bleached floorboards hidden under new carpet,

A piss stain on the floor of an unused bedroom.

Squat and furious, my father stands

In the middle of Methyl Street.

My superball in his right hand, he slams it hard

Against the asphalt, making it

Bounce so high my nine-year-old eyes can’t see it.

The fingers of his old mitt, long and dark,

Like bad bananas, sit on my left hand

As I camp under the ball, half-brave

Half-fearful, of its return.

There will be an awkward pause,

A scuffling of shoes and downward glances.

One who worshipped from afar,

Tongue tied by his own good fortune.

One who was already a god,

Now transfigured and embarrassed.

“Uh, I know now how much I meant to you,”

With a slight dip of his head

As his sentence runs out of bounds.

“Yeah, well, it’s like this,”

The elder will slowly admit,

“I cried when I saw you run.”

O Gods of my youth,

Deities of the House and the Street,

Men of Pain and Men of Power,

Look down on me just once

And smile.

for Laurie King

You turned—

Blood red on your lips,

Cratered cavern in your hand,

To offer the unknown,

The exotic,

The crunch.

You knew

What I did not,

That sweet must melt

With sour,

That smooth and bland

Are not enough.

I stopped—

Put down my book

And stared:

An upturned palm,

A cardinal shell,

And seeds.

The doubling

Made your silent point:

Seed for seedling,

One untried,

One unsure,

Both broke open.

But yours was more:

Mature, adult,

Loss of the certain.

Plucked and placed,

I chewed on wonder.

Your smile told me

That little-boy worlds

Enlarge to compass

Bloods of passion and pain.

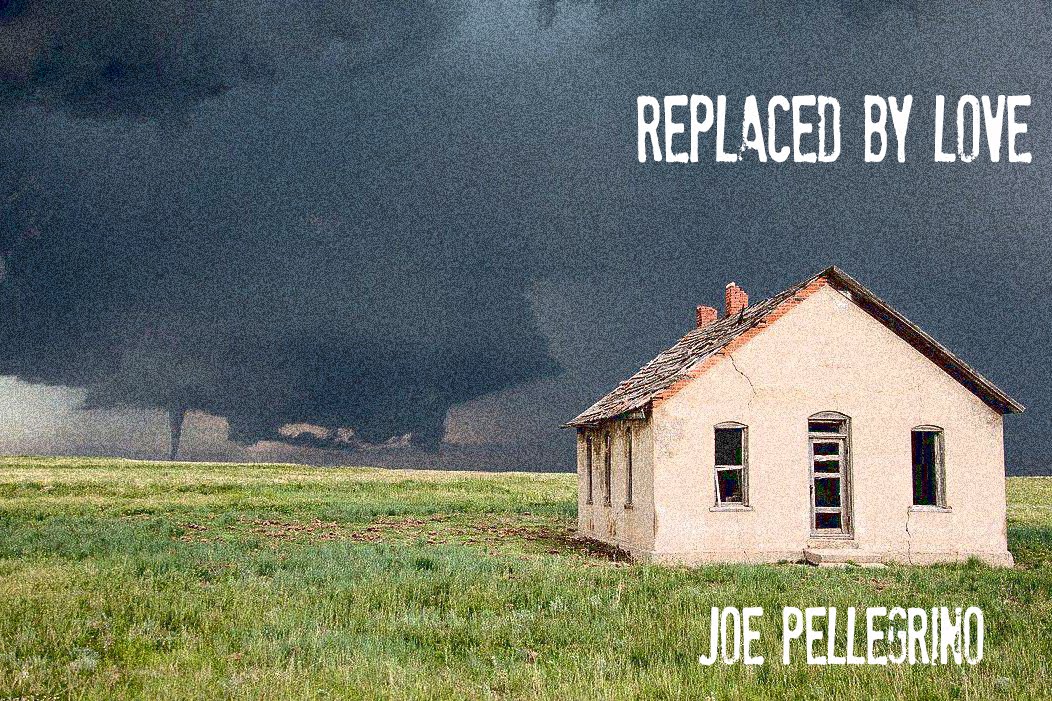

The Dante

We were reading then

lost faith—

Replaced by love.

Hades and Persephone,

Demeter, Ugolino,

Francesca, Paolo,

Brunetto, Pyramus,

No matter the person

No matter the place,

In scarlet complications,

Love allures.

He knew it for what it was,

That bunt with two strikes in slow-pitch softball:

A desperate move, acquiescence to time,

Recognition that he was no longer:

Penn State fullback,

Steeler star,

Immaculate Receiver,

Four-star General of Franco’s Italian Army.

Now he was merely the fleet

Captain of airport lots.

It rolled its six feet,

White on green, ball on grass, age on youth,

And he began his hobbled stumble to first.

I remembered when we could glide

Through the secondary,

Sidestep tackles,

Slip through holes that closed behind us.

And so I longed to leg out

All my aching two-strike bunts,

My long negotiations with the real.

Awkward it was, that letter-man meeting

One did it bodily.

Two with their words.

One always politic

And shy of condescension,

Doughy and pale.

One could speak of the post,

But deferred to those he thought his better,

Rather talking of music and love.

The third thin man

Whose father’s forlorn baritone

Sang Volare

Like some Rust-Belt Orpheus

Or haloed, hoary saint

Silhouetted by memory

Could have translated for them,

Telling them that love was work

And work was love.

But instead, he smiled,

For this the Postman

Already knew.

I know the special ache in the forearms, the palms;

The holes in the body that feel the loss when she is gone,

Even just across the room, in her mother’s arms.

I long to hold her close to my face, to feel her cheek on mine,

To smell the seasons on her skin, the milk on her breath,

To give to her, to shield, protect, provide

And once, just once, to have her fingers clutch my shirt,

To see her eyes brighten, her voice squeal,

As my lips brush her ear to whisper,

“Sleep, love, and we will save you.”

for Nick

I had just turned twelve three days before

We heard the news,

Standing breathless in the living room.

It couldn’t be true. He was a man above.

His friends lived on our block; we knew his kids.

He was always there in right, catching

Those who dared to make the turn at first too wide.

Loping out, throwing a few off the wall,

Always aloof, looking at his shoes,

Almost embarrassed, but too full of pride to give in.

The slow twists of his neck, as if his spine

Was grinding out his hits.

The look down his arm to the pitcher . . .

Buried deep in the box, he could knock it and run

Like a present coming unwrapped.

Just that last year he’d hit three thousand.

Stood on the base, bent his head, took off his cap.

Taking in the thunder that should have been his

Many years before.

So Nick and I looked at each another,

Our little-boy pride overtaken by little-boy tears.

That New Year’s night, lying in bed, we talked stealthily,

Bluffing with one another,

Hoping for uncharted islands or triangulated returns.

But even at twelve and ten we knew better.

He was smart enough to handle the plane;

Finesse it in some crosswind, fielding it

Like a carom off the ivy.

But he never got the chance to play it.

This ball was never bound for his field.

We rolled over, quiet, and stared up at the ceiling.

Both bereft, both trying to be strong,

Both hopelessly hoping.

It wasn’t until the dewy Florida mornings of Spring training

That I told myself the truth:

He was gone, and the only thing that remained

Was the burning in our cheeks when we thought of him;

The hurt and desertion that only little boys can feel,

When the world punishes the bewildered excess of love.

Yes, there were good times to come, but not on his field.

The sweet years of Terry, Franco, Smiling Jack, Mean Joe.

But there was an autumnal taste, a knowledge we now had.

We saw it in each other’s eyes: “This could all go away tomorrow,

Just like Roberto.”

Nobody watches movies in movies,

Like nobody reads poetry in poetry.

Oh sure, we refer, we allude,

But we never really read and respond.

But there are movies about movies,

And I guess there are poems about poems.

Many look into Chapman’s Homer

And hope someone catches the allusion.

And where does all this get us,

This self-reference and deprecation?

Does it make us better writers

Or readers, or human beings?

Or does it merely let us

Show off our erudition,

As if we had an audience? Though

No one is watching.

On my way up the mountainside I saw a chunk

Of white marble, traced with red,

About as big as my fist.

I carried it for a while, about two hundred paces,

Then realized I would return the same way.

So I placed it on top of a post which marked the trail,

For I knew it would wait there for me.

In a clearing beyond the logging roads

I could look to the right to see Glenn Da Lough

And to my left see all of Wicklow laid out like a Kelly tablecloth.

There were ferns at my feet,

Timeless as this mountain,

Carving out an existence between the pines and the gravel,

Silly fronds curling and uncaring.

I looked ahead and saw a couple sitting on the trail,

Turned in to one another like the fronds.

Sure that they wanted their privacy

As much as I wanted mine, I walked down the way I came.

But before I left I looked down,

To see a small flower so yellow

That even a real poet couldn’t describe it.

A thorny gorse that hadn’t grown up yet.

Nor would it get the chance, because I picked it,

And put it in a map to carry back.

Knowing that, after only an hour or so,

It would lose most of its color,

Fading as it served me for a souvenir.

Returning, I saw the rock I had chosen, carried, and placed.

I picked it up, kissed a red vein, then tossed it,

Watching it bounce down the hillside

Among the timeless ferns.

He’s bent and fumbling, smaller somehow,

Gray-haired, trembly,

As Parkinson’s shakes away his strength.

Once a chorister, his ears and voice have left him now.

But gone too is the anger, and the frustration.

His many sicknesses have tried and purified him,

Have burnt out the temper, the pent-up rage

At being a two-bit man in a four-bit world.

Now all that remains is this stumbly husk,

Breaking into tears, balancing his meds.

Her? She’s still the same:

Gentle, judgmental, and over all the shine of placidity.

The years have steeled her, bracing her

For the fight of her eighties,

The fight of her life, the fight of her death.

Little change on the inside;

Still the strong one. Despite his tirades and explosions,

She was the one who did the work, the one who

Doled the money, the one who held the power.

She is the one who can live on her own.

In the beginning, it was different.

She was of a certain age, a professional with a mother in tow.

And, except for Alaska with the Army,

Where he was given a shovel instead of a rifle,

He had never left home.

She moved two doors away, and they were set.

Married within a year, despite dire warnings.

“You’re not old enough for her,” they told him,

While others questioned why he was her Lolita.

They survived, forty years,

Despite what they knew,

Despite the gambling,

Despite the talk of divorce,

Despite the kids who put them through hell.

And now they lean on one another,

White on white, wizened on wizened,

Slow bodies betraying the speed of their intentions.

The shells of life, the husks of love.

Open arms and all smiles as I walk through the door.