How to Read a Poem

We often speak and write in extremely literal terms, because we want to make sure we are understood. So when communication is incoming, we look at it the same way and try to extract its literal meaning.

But this doesn’t work with poetry. Great poetry is not literal, almost by definition. As art, it shows us a higher truth that is expressed in a nonliteral, nonlinear way, a way that is completely original to the artist who has composed it. So the very first thing you have to do is try to tamp down your desire for literal certainty when you encounter poetry. Just read it quietly, then read it aloud, let the words roll around in your mind for a while, and enjoy it as an artistic experience.

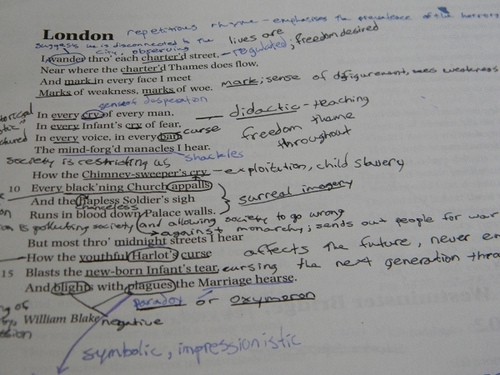

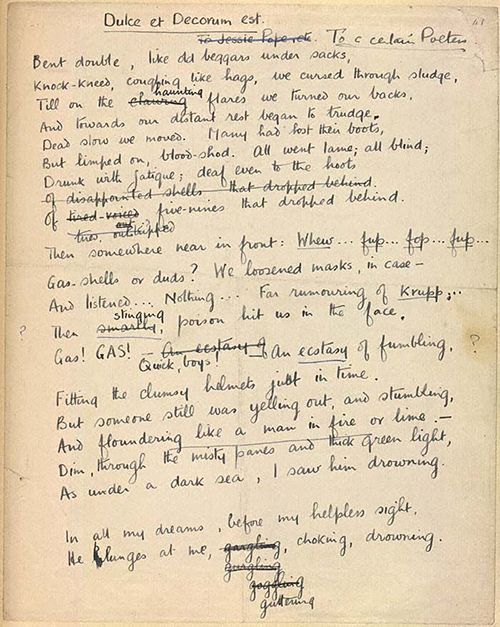

Take notes as you read

Read poetry with a pencil in your hand.

Mark it up; write in the margins; react to it; get involved with it. Circle important, or striking, or repeated words. Draw lines to connect related ideas. Mark difficult or confusing words, lines, and passages.

Read through the poem several times, both silently and aloud, listening carefully to the sound and rhythm of the words.

Start with the title

Consider the title of the poem carefully. What does it tell you about the poem’s subject, tone, and genre? What does it promise? (After having read the poem, you will want to come back to the title in order to consider further its relationship with the poem.)

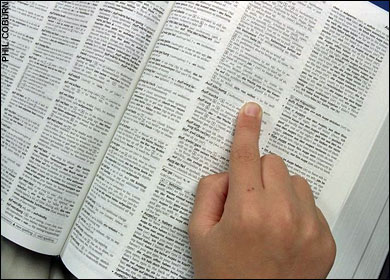

Get the meaning of every word

Poems use compressed language, so it's important to know what every word means. If the poem is written in sentences, can you figure out what the subject of each one is? The verb? The object of the verb? What a modifier refers to? Try to untie any syntactic knots.

Are there difficult or confusing words? If you're the slightest bit unsure about the meaning of a word, look it up.

Be sure that you determine how a word is being used — as a noun, verb, adjective, adverb — so that you can find its appropriate meaning. Be sure also to consider various possible meanings of a word and be alert to subtle differences between words.

One way to see the action in a poem is to list all its verbs. What do they tell you about the poem?

Find the subject

What is your initial impression of the poem’s subject? What is the poem’s basic situation? What is going on in it? Who is talking? To whom? Under what circumstances? Where? About what? Why? Is a story being told? Is something — tangible or intangible — being described? What specifically can you point to in the poem to support your answers?

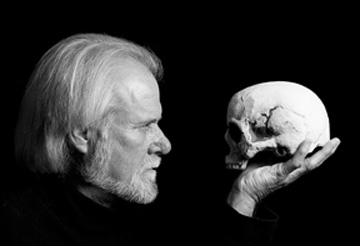

Find the author

Is the author speaking in her own voice? What is the author’s attitude toward the subject? Serious? Reverent? Ironic? Satiric? Ambivalent? Hostile? Humorous? Detached? Witty?

What do you know about this poet? About the age in which he or she wrote this poem? About other works by the same author?

Put it in your own words

Try to paraphrase the poem, retelling it in your own words, out loud, moving line by line through it. Try writing out an answer to the question, “What is this poem about?” — and then return to this question throughout your analysis. Push yourself to be precise; aim for more than just a vague impression of the poem.

What techniques are being used?

Is the poem built on a comparison or analogy? If so, how is the comparison appropriate? How are the two things alike? How different? Does the poem appeal to a reader’s intellect? Emotions? Reason? Are there any allusions to other literary or historical figures or events? How do these add to the poem? How are they appropriate?

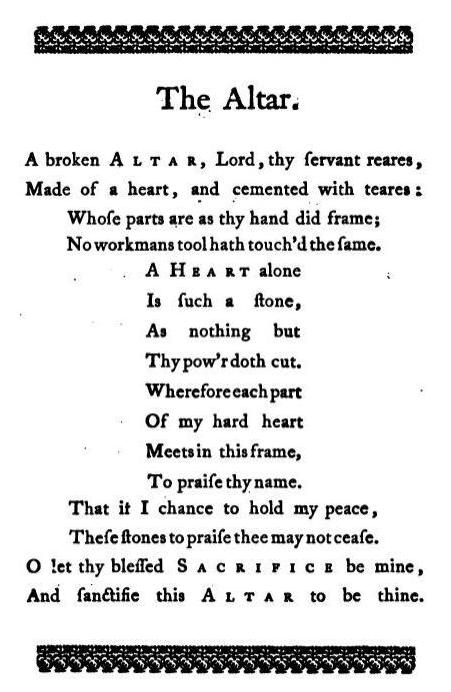

Look at the form

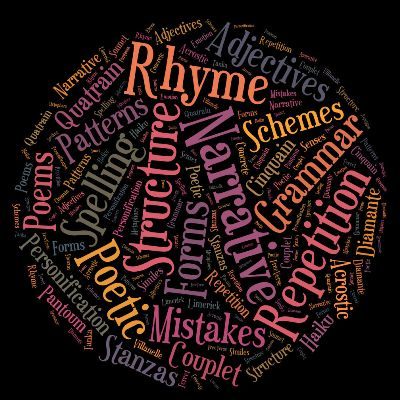

Consider the sound and rhythm of the poem. Is there a metrical pattern? If so, how regular is it? Does the poet use rhyme? What do the meter and rhyme emphasize? Is there any alliteration? Assonance? Onomatopoeia? How do these relate to the poem’s meaning? What effect do they create in the poem?

Are there divisions within the poem? Marked by stanzas? By rhyme? By shifts in subject? By shifts in perspective? How do these parts relate to each other? How are they appropriate for this poem?

How are the ideas in the poem ordered? Is there a progression of some sort? From simple to complex? From outer to inner? From past to present? From one place to another? Is there a climax of any sort?

Do you recognize an overall form for the poem? Sonnet? Ballad? Haiku? Terza Rima? If so, what do you expect from a poem in such a form?

Look at the poet's choice of words

A good poet uses language very carefully; as a good reader you in turn must be equally sensitive to the implications of word choice. What mood is evoked in the poem? How is this accomplished? Consider the ways in which not only the meanings of words but also their sound and the poem’s rhythms help to create its mood.

Is the language in the poem abstract or concrete? How is this appropriate to the poem’s subject?

Are there any consistent patterns of words? For example, are there several references to flowers, or water, or politics, or religion in the poem? Look for groups of similar words.

Does the poet use figurative language? Are there metaphors in the poem? Similes? Is there any personification? Consider the appropriateness of such comparisons. Try to see why the poet chose a particular metaphor as opposed to other possible ones. Is there a pattern of any sort to the metaphors? Is there any metonymy in the poem? Synechdoche? Hyperbole? Oxymoron? Paradox?

Wrapping it up

Ask, finally, about the poem, “So what?” What does it do? What does it say? What is its purpose?