Irish Literature Since 1850

ENGL 5236 / 5236G

Spring 2025

Course Information

ENGL 5236 / G Irish Literature Since 1850

Section 01F

CRN: 11218 / 11223

Online Course, Synchronous Instruction

TR 3:30 - 4:45

Zoom link: https://georgiasouthern.zoom.us/j/81554720467?pwd=hQ2bYurr9D4QaWrrJMRTIaUzgWamO4.1

Course Description, from the University's Academic Catalog

An examination of representative Irish poetry, prose, and drama since the Great Hunger of the 1840s. The course interrogates literature from the Irish Cultural Revival; the Easter Rising, War of Independence, and Civil War; the Free State; the Northern Irish Troubles; and the Celtic Tiger. All works are in English or English translation. Cross Listing(s): ENGL 5236G. Repeat Limit: Not Repeatable

Course Dates

January 13: Full Term, Classes Begin, Attendance Verification must be completed on the first class meeting day

January 13-16: Full Term, Drop/Add, Ends at 11:59 P.M. on January 16

January 20: Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday - Administrative offices closed - No classes

March 10: Full Term, Last day to withdraw without academic penalty

March 17-22: Spring break for students

May 5: Full Term, Last Day of Classes

May 8: 3:00-5:00 Final Exam

Learning Outcomes/ Career Readiness Competencies

Learning Outcomes are the knowledge or skills you should gain (and be able to demonstrate) by the end of a particular course.

Career Readiness Competencies are competencies developed by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). They address eight areas where employers agree that your abilities and skills signify your readiness to begin and/or extend your career. Below are the skills you'll have the opportunity to practice in this course.

Learning Outcomes:

Upon successful completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Analyze works of Irish literature from 1850 to the present to examine how these works reflect Irish cultural identity, historical experiences, and responses to colonialism.

- Evaluate the historical and cultural significance of Irish literature to 1850, considering the ways in which Irish writers engage with themes of colonization, exile, and cultural hybridity.

- Apply critical concepts of Irish literature and literary approaches to interpret and contextualize Irish literature in relation to broader historical, cultural, and political contexts.

Career Readiness Competencies contained within this course:

| Self-Development | Communication |

|

|

| Critical Thinking | Equity and Inclusion |

|

|

| Leadership | Professionalism |

|

|

| Teamwork | Technology |

|

|

These career readiness skills will serve you well no matter what your next steps after graduation might be. Find out more about them on this page of the NACE site.

Required Material

Yeats, W. B. The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats, 2nd Revised edition. Edited by Richard J. Finneran. Scribner, 1996. ISBN: 978-0684807317. (Amazon: $12.79) |

|

Joyce, James. Dubliners. Edited by Laurence Davies and Keith Carabine. Wordsworth Editions, 1993. ISBN: 978-1853260483. (Amazon: $3.95) |

|

Kavanagh, Patrick. Collected Poems, First American Edition. W. W. Norton & Company, 1964. ISBN: 978-0393006940. (Amazon: $16.54) |

|

Heaney, Seamus. Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966-1996, Reprint edition. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999. ISBN: 978-0374526788. (Amazon: $10.39) |

|

Keegan, Claire. Small Things Like These, International edition. Faber & Faber, 2022. ISBN: 978-0571368709. (Amazon: $14.23) |

|

Material available in the Folio site (in .pdf or .docx format): |

Trigger Warnings

A “trigger” is anything that might cause a person to experience a strong emotional and/or psychological response. Some triggers are shared by large numbers of people (for example, rape), while others are more idiosyncratic (for example, orange juice).

All texts read in this course, all class discussions, and all ancillary materials may contain instances of the following potential triggers, as well as other unanticipated and so unlisted potential triggers: ignorance; willful ignorance; cultural insensitivity; oppression; persecution; swearing, abuse (physical, mental, emotional, verbal, sexual), self-injurious behavior (self-harm, eating disorders, etc.), talk of drug use (legal, illegal, or psychiatric), suicide, descriptions or pictures of medical procedures, descriptions or pictures of violence or warfare (including instruments of violence), corpses, skulls, or skeletons; needles; racism; classism; sexism; heterosexism; cissexism, ableism; hatred of differing cultures or ethnicities; hatred of differing sexualities or genders; body image shaming; neuroatypical shaming; dismissal of lived oppressions, marginalization, illness, or differences; kidnapping (forceful deprivation of or disregard for personal autonomy; discussions of sex (even consensual); death or dying; beings in the natural world against which individuals may be phobic; pregnancy and childbirth; blood; serious injury; scarification; glorification of hate groups; elements which might inspire intrusive thoughts in those with psychological conditions such as PTSD, OCD, or clinical depression.

Unless expressly stated otherwise, the views, findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the texts read in this course, the classroom discussions, and the ancillary material do not necessarily represent the views of the University or the course instructor.

All texts read in this course, all class discussions, and all ancillary materials may also contain instances of overwhelming beauty, profound truths, and serious reflection on what it means to be human.

By remaining registered in this class, you agree to be exposed to all of the above. As Jenny Jarvie has written,

Structuring public life around the most fragile personal sensitivities will only restrict all of our horizons. Engaging with ideas involves risk, and slapping warnings on them only undermines the principle of intellectual exploration. We cannot anticipate every potential trigger—the world, like the Internet, is too large and unwieldy. But even if we could, why would we want to? Bending the world to accommodate our personal frailties does not help us overcome them.

— Jarvie, Jenny. “Trigger Happy.” The New Republic, 3 March 2014.

In short, texts and/or discussions in this class may make you uncomfortable. . . for many of them, that may be the whole point.

COURSE STRUCTURE

Classes

While an online synchronous course isn't as immediate as a face-to-face class (my view of you all is a grid of 2" x 2" wallet-sized photos), it certainly beats an online asynchronous class. And it also has a few advantages. Our "classroom" allows me to record each class period. After Zoom compiles the videos, I'll place links to them in Folio, so you can go back to any of them if you want to review some material or if you missed a particular class.

However, the existence of recordings shouldn't keep you from taking notes (more on this below). In fact, you should have two sets of notes for each work: the notes you take when you read the piece, and the notes you take during class. If you're really good at note-taking, you can actually amplify/redirect/correct your initial notes with the ones you take in class.

"The Silent Professor"

While the ability to record each class is certainly an advantage, communicating through a computer is just not as conducive to real interaction as an actual classroom would be. It's far too easy for me to just drone on for the entire class period, and you end up just consuming information rather than actually thinking about these texts. So, in an effort to get you more engaged with the material, after the first couple of weeks of class, I'll be relying on you, as a group, to further our conversations about these texts. I'll give you some ideas about what I think you should focus on, and then I'll just try to stay as quiet as possible. I know the salient points you to get to, and when, as a group, you touch on them all, we'll move on. It may take us a bit longer to get through the material this way, but what good is understanding these texts if you can't articulate that understanding? Yes, it'll be awkward at first, and I'll have to bite my tongue to keep from jumping in and filling those awkward silences, but once you overcome your initial reticence, I think you'll get more out of the class.

Readings

As you will see in the schedule below, there are a variety of genres represented in this class, but there's quite a bit of poetry, more than some of you may be comfortable with. I've set up the class this way for two reasons; the first is philosophical and the second is practical. Primarily, I think the best way to capture the zeitgeist of a particular historical moment, or to understand the impact of a literary movement, is through poetry. Works in this genre contain far more distilled language than those in any other genre, so it's easier to get at the essence of the subject at hand. Also, studying poetry allows us to cover far more ground. We could spend the semester reading only novels, but the nature of the academic calendar means that we would deal with far fewer texts, and you'd be familiar with far fewer authors.

At a practical level, all of the reading material I'll pass to you is in the Adobe portable document format (.pdf). Since this is an online class, you can, of course, read all this material on a computer or another device. However, I'd suggest printing out the text to read it, because going through some of these longer pieces can get tiring if you're looking at them on a screen.

Notes

Another reason for printing out the texts is that you can take much better notes on them that way. And make no mistake about it, YOU SHOULD BE TAKING NOTES ON THESE WORKS AS YOU READ THEM. Believe me, you will have a much harder time in this class if you don't take notes on what you're reading.

Taking notes is an essential part of the reading process. It helps you internalize difficult ideas by putting them into your own words and can help you be more focused when you're reviewing for the exams. You're far more likely to remember material you have thought about and made notes on than material you have read passively.

Beyond marginal glosses, which you should be making, many students find it effective to take notes in two stages:

- Write down the main points (the setting, major plot points, characters, etc.)

- Summarize, condense, and organize those initial notes, making as many connections between those notes and your own experiences as you can.

In general, your notes should be brief and to the point.

- Don't attempt to write everything down, just reflect the main themes. Aim to get the gist of the topic or the main points.

- If you come across something you don't understand, make a note of it and come back to it later.

- Don't lose track of your purpose in taking these notes in the first place; keep focused.

- Don't worry about whether anyone else could make sense of your notes; you're the only person who needs to read them.

If you come to see me to ask how you should study for the exams, or even what you should be studying for those exams, the first thing I'm going to ask is to see the notes you've taken. If you don't have any notes from your reading and from our class sessions, or if those notes are thin and incomplete, there's not much I can do to help you succeed in this class.

Exams

We'll have two exams, one halfway through the course and one at the end of the course. But here is where the convenience of this mode of delivery costs you something. I could make these exams available only during our class time, then have you take the exam as I watched over you. But, let's face it, some of you are not at your best at 3:30 in the afternoon. Maybe you're a morning person. Maybe you're a night owl. But I don't know many people who can say "I really hit my stride at about 3 each afternoon."

So I'll make each exam available from midnight to midnight on the dates noted in the schedule. You may take the exam at any time on the day that is it available. For your first exam, once you open the exam, you'll have one and a half hours to complete and submit it. For your second exam, since it is the final (but it is not cumulative), once you open the exam you'll have two hours to complete and submit it.

That all sounds fine and dandy, doesn't it? But here's the part you may not like as much: the first eaxam will be on a Wednesday, a day when we normally don't have class. We'll have classes that Tuesday and Thursday, so I feel like I get one more class period with you, devoted to the material, rather than to the exam.

Exams are listed on the syllabus, on the schedule, and in the calendar in Folio. If you miss an exam because you misread the date, or because you didn't check any of the multiple places that tell you when it is, you should not expect to take it at a later date. If, however, circumstances cause you to need to take an exam early, please let me know and we will come to some accommodation.

Projects

Rather than traditional written responses, analyses, close readings, or researched papers, you'll be responsible for a Digital Humanities Assignment (where you'll do plenty of research, then distill what you find into glosses and notes that will help support other students) and a Multimodal Found Essay Assignment, where first you'll curate a number of primary texts, images, videos, secondary material, and/or material in other media that surround one of the major themes of the class, then reflect on your process and explain why and how you made the choices that you did.

Both assignments are explained in detail below.

Just for Graduate Students

While this isn't a seminar, and so I don't feel right asking for an article-length researched paper from you, you do have a higher set of expectations for your work in this class. So while the undergraduate students are working on their Multimodal project, you'll be crafting a researched paper of no less than 3,000 words (your Works Cited and any block quotations are excluded from this count). If I have to specify a number of secondary sources you should be able to summarize, paraphrase or quote, I'd say you need a minimum of six (primary sources don't get added to this count).

While I won't mandate that you run each section of your work by me, I'll need a paper proposal from you, with a tentative bibliography of ten sourses, or an annotated bibliography of four sources, by March 1.

COURSE EXPECTATIONS

Learning Commitment

The "Carnegie Unit" is how universities define credit hours and categorize the amount of work students do for each credit hour. Each credit requires fifteen "contact hours" which are essentially the hours you spend in class during the semester. And each contact hour requires two hours of outside work, or time devoted to the class that doesn't happen in the class. This is a three-credit course, with 45 contact hours. Those 45 contact hours necessitate at least 90 hours of out-of-class work on your part. That's at least 135 hours committed for each three-credit class that you take.

It's easy to lose sight of this fact in an online course. And I certainly didn't set up this course thinking that you'll devote exactly nine hours each week to it. But remember, reading takes time. You might need a full nine hours to read some of the longer texts we're covering in this class.

If you're not a self-starter, or you have problems with deadlines, or you just don't think you can commit to this level of work, you should probably look for another section of this class.

Academic Integrity

I expect that you will conduct yourself within the guidelines of the Honor System. All academic work should be completed with the high level of honesty and integrity that this University demands.

I do not tolerate academic dishonesty. Beyond the moral implications, I find it insulting. All instances of plagiarism will be reported to the Office of Student Conduct. Any instance will result in an F in the course and possibly further sanctions. Plagiarism is presenting someone else's work as your own without giving them credit. Someone else is defined as anyone other than you: another student, a friend, relative, a source on the Internet, articles or books. And work is defined as ideas as well as language. So taking someone else's ideas and putting them in your own words—or using someone else's words to express your ideas—is plagiarism. And, in the case of friends and family, it doesn't matter if they give you permission.

A note about group work: I encourage you to read and discuss these texts together outside of class. It is, in fact, the core of our endeavor, to hone our own ideas on these texts through discussions with others. You should also discuss your writing with your classmates, as hearing a number of ideas will help you create and polish your own. However, this does not mean that you should write your papers as a group. While discussion is obviously a group activity, writing is a solitary one, and should be treated as such. Any attempt to subvert this would be an instance of academic dishonesty.

The University has a more extensive definition of Academic Dishonesty (from the Student Conduct Code):

CHEATING

- submitting material that is not yours as part of your course performance;

- using information or devices that are not allowed by the faculty;

- obtaining and/or using unauthorized materials;

- fabricating information, research, and/or results;

- violating procedures prescribed to protect the integrity of an assignment, test, or other evaluation;

- collaborating with others on assignments without the faculty's consent;

- cooperating with and/or helping another student to cheat;

- demonstrating any other forms of dishonest behavior.

PLAGIARISM

- directly quoting the words of others without using quotation marks or indented format to identify them;

- using sources of information (published or unpublished) without identifying them;

- paraphrasing materials or ideas without identifying the source;

- Self-plagiarism: re-submitting work previously submitted without explicit approval from the instructor;

- unacknowledged use of materials prepared by another person or agency engaged in the selling of term papers or other academic material.

Should you wish to pursue a case of academic dishonesty through the Office of Student Conduct, I will speak at your hearing and send a copy of this syllabus along with the documents in question to the Hearing Officer, so a plea of ignorance or non-malicious intent on your part will not be valid.

COURSE SCHEDULE

Reading should be a pleasure; it is most certainly a privilege. With the texts below you should grab the opportunity to read as far as you can as soon as you can.

DATE |

CLASS ACTIVITY |

DUE |

|---|---|---|

01/14 |

Introduction / Syllabus / Background |

|

01/16 |

||

01/21 |

||

01/23 |

Le Fanu: Carmilla |

|

01/28 |

Le Fanu: Carmilla |

|

01/30 |

Early Yeats: "The Stolen Child" "To an Isle in the Water" "Down by the Salley Garden" "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" "When You Are Old" "Who goes with Fergus?" "To Ireland in the Coming Times" |

|

02/04 |

Gregory: from Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland |

|

02/06 |

Wilde: "The Canterville Ghost" |

|

02/11 |

Synge: Riders to the Sea |

|

02/13 |

Early/Middle Yeats: "Adam's Curse" "In Memory of Major Robert Gregory" "An Irish Airman foresees his Death" Easter, 1916 |

|

02/18 |

Joyce |

|

02/20 |

Joyce | |

02/25 |

ACIS-BCPS Conference: class cancelled |

|

02/27 |

Joyce |

|

03/04 |

Middle/Late Yeats: "The Second Coming" "Leda and the Swan" "Sailing to Byzantium" |

|

03/05 |

EXAM 1 AVAILABLE |

|

03/06 |

Late Yeats: "Among School Children" "Under Ben Bulben" "The Circus Animals' Desertion" |

|

03/11 |

Kavanagh |

OED Assignment |

03/13 |

Kavanagh |

|

03/25 |

Kavanagh | |

03/27 |

Heaney, poems |

|

04/01 |

Heaney, poems |

|

04/03 |

Heaney, poems |

|

04/08 |

Heaney, poems |

|

04/10 |

Boland, poems | |

04/15 |

Boland, poems |

|

04/17 |

McGuckian, poems | |

04/22 |

McGuckian, poems |

|

04/24 |

Keegan: Small Things Like These |

MM ASSIGNMENT |

04/29 |

Keegan: Small Things Like These |

|

05/01 |

Keegan: Small Things Like These |

|

05/08 |

EXAM 2 AVAILABLE |

INSTRUCTOR

My 27thFirst Day of School as a professor.

Dr. Pellegrino

I'm Dr. Joe Pellegrino, an Associate Professor in the Literature department. I teach lots of different classes. My specialties are Irish literature and postcolonial literature, so I end up doing classes that don't fit into the standard Brit Lit/American Lit model: Irish lit, African lit, etc. But I also do canonical figures. For instance, this semester I'm also teaching a graduate seminar on the poetry of T.S Eliot.

It seems like I went to school forever, and went to lots of different schools: Duquesne University, St, Louis University, Mannes College of Music, The New England Conservatory, and UNC-Chapel Hill, which is where I did my last degree. I've also taught at a lot of schools: Duquesne, UNC, Eastern Kentucky University, University of South Carolina-Upstate, Greenville Tech, Converse College, and here at GS. I've got some experience in online education; I was a University Director for the (short-lived) Kentucky Commonwealth Virtual University, and have taught online classes for over 20 years now.

Professionally, I also edit an international journal, The International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. I'm interested in a number of fields, but most of my publications are either on Irish studies, postcolonial lit, or teaching. I'm currently ghost-writing the University's Compliance Certification Narrative, a once-a-decade production that we give to our accrediting body so we can keep the doors open for the next 10 years. When it's all done, it'll be about 800 pages of text, with over 4,000 separate files linked to it.

I have only one item on my bucket list: to see the Northern Lights. One day I'll get there, but in the meantime I'm raising two daughters, making heirloom furniture (pretty much a middle-aged guy cliché), keeping up with new technology, wishing I could spend more time doing music, and trying to keep my head above water.

Contact Information

Office:

Room 3308B, Newton Building

Phone: 912.478.5953

Office Hours: MW, 12:00 - 4:00

Email: jpellegrino@georgiasouthern.edu

English Department in Statesboro:

Room 1118, Newton Building

622 COBA Drive

Statesboro, GA 30460

912.478.0141

In-person and Virtual Office Hours

During the semester, I will be working half-time at the University's Office of Institutional Assessment and Accreditation. That means I'll be in my office in Newton for in-person only on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

I'll be available for drop-ins, or be able to zoom with you, on those days from 12 noon to 3 pm. I can be available at other times on those days, but you'll need to email me to set up an appointment for those times.

A WORD ABOUT EMAIL

OK, maybe two words: CONTENT and FORM

CONTENT

Please don't hesitate to post to me if you have a question about any of the readings, especially if you're struggling to figure them out. But please think twice about posting questions where the answer is in this syllabus. If you do, I have two options for a reply: I can copy and paste material from the syllabus or schedule just for you—because you didn't actually check it yourself—or I can reply with something like "check the syllabus" or "check the schedule." Both of these options are redundant, because you already have access to the answer to your question, and you should already know to check the syllabus. And both of these options reflect poorly on your abilities, either to understand what is required of you or to comprehend what you have read. Since I don't want to think less of your abilities, neither of these options are satisfactory. So if you ask a question that is already answered in the syllabus or in the schedule, I won't be replying at all.

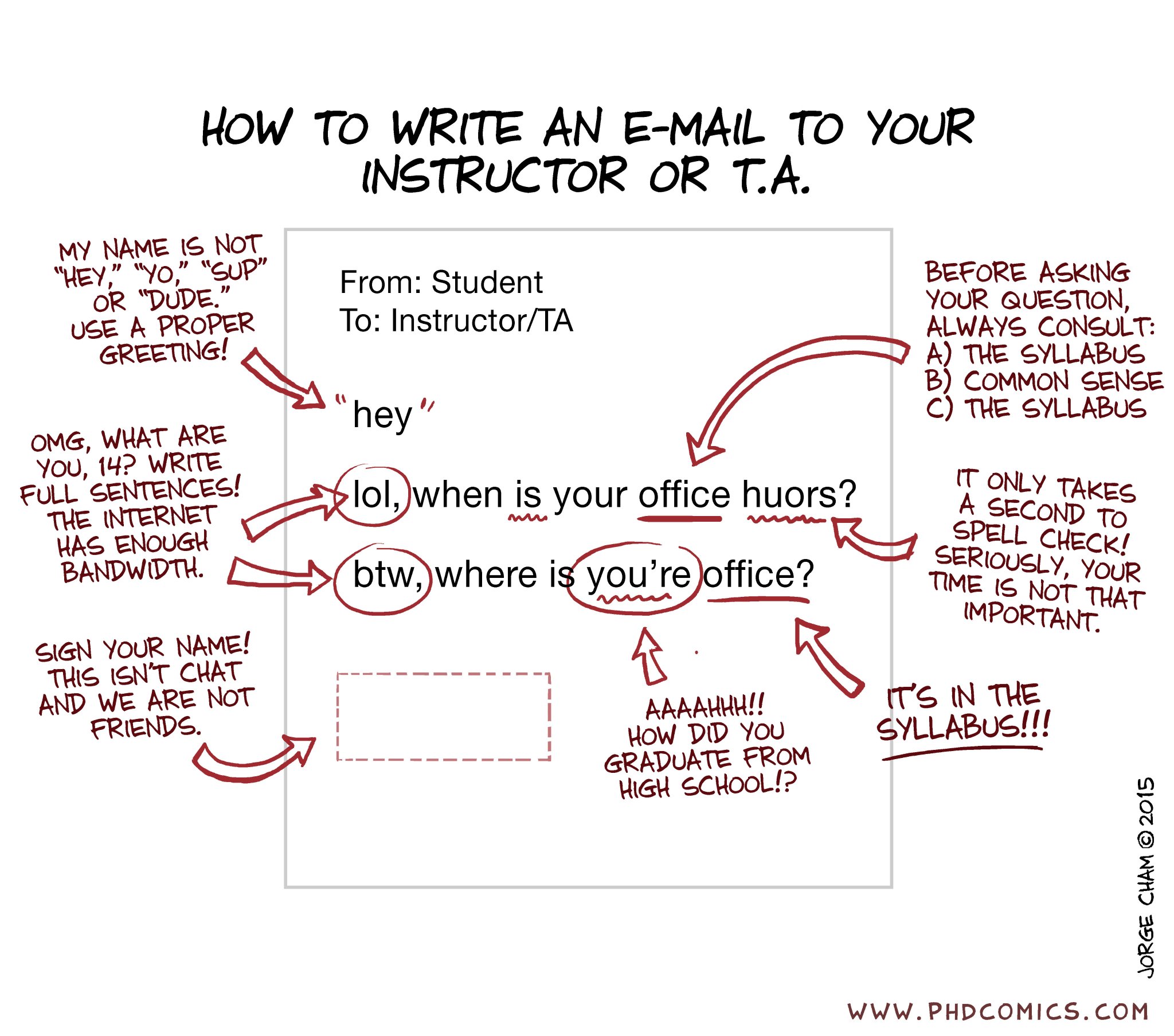

FORM

See that image right above this? It's not just some funny advice about how to write an email to one of your instructors or teaching assistants; it's a guide to acting like an adult, so it's something we expect you to follow. When you write anything, you change the form to suit the content. So you don't write an email to a professor like you're writing a DM to your friend. Look at the graphic, then follow the rules on it.

And as with the questions that have already been answered in this syllabus, I could embarrass you by reminding you of those rules when you don't follow them, or I could just not respond to you until you actually get it right. And just in case you can't parse what those rules are, I'll put them into a list:

- My name is not "Hey," "Yo," "'Sup," or "Dude" — use a proper greeting.

- Don't use acronyms or texting shorthand — write in full sentences. Use a grammar checker.

- Spell-check it before you send it. When you have tools available to you and you don't use them, you're not only demonstrating that you don't know how to communicate at anything beyond a middle-school level, you're also demonstrating your inability to use simple tools in order to make yourself look better.

- Check the syllabus before you make yourself look foolish (see the previous point).

- Sign your name.

So let me sum this all up:

if you don't hear back from me after you sent me an email, it's either because you can't write an email correctly for the audience you're trying to address, or you're asking a question that I've already answered in this document.

CLASS POLICIES

Attendance

The University Undergraduate Catalog states unequivocally: “Students are expected to attend all classes.” Attendance in this class is not optional. Attending class means that you are present and attentive for the whole class period and that you are prepared for the day’s lesson. Unless you are missing class for a University-sanctioned reason, missing class, regardless of the excuse, will be counted as an absence.

But life gets complicated. So you'll have a free pass to miss almost 15% of our classes, regardless of the reason. You can miss because it's a nice day and you don't want to be inside, or your friend is coming in from out of town, or you were just up too late last night. The reason doesn't matter. Now, let me be clear, I certainly don't encourage you to miss any classes that you're physically well enough to attend. But I'll give you two weeks of absences (that's four classes) before your absences begin to negatively affect your grade for the class. If you are absent more than four times, regardless of the excuse, your final grade will be lowered by one point for every subsequent absence.

If you have to miss more than your allotted absences, there is obviously something going on in your life that does not allow you to pursue this degree wholeheartedly, so you should consider withdrawing from the course, if not the University. Keep this in mind when using your absences—that’s ALL you will be allowed. You do not want me in the position of deciding whose excuse is valid and whose isn’t, so I don’t need any documentation for your absences. If you’re within the limit it is not necessary, and after the limit it will not matter.

By now you recognize that arriving on time for class is, at its core, a sign of respect for your classmates and your professor. Tardiness, therefore, is a statement saying that your time is more important than anyone else’s. I will strike a blow for the group by counting every instance of tardiness as 1/3 of an absence. So, if you’re doing the math, you can be tardy several times without any consequences, save the collective disdain for your actions. And yes, your tardiness works in conjunction with your absences, so a combination of the two will push you toward the negative consequences outlined above.

Since this is a synchronous online class, being present means being in the zoom with your camera on and your microphone muted (unless you wish to speak, which I wholeheartedly encourage).

Writing Proficiency

If you need additional work on the surface features of your writing, I'll let you know. Basically, if I can't understand what you're trying to say in your first paper, then you'll have to work at writing more clearly. I'll ask you to schedule sessions at the Writing Center in order to be more successful on your next paper.

The reason professors make students write papers is not because we love to mark them up, or because we somehow enjoy this. I'm willing to bet that every professor you ask would say that marking and grading papers is the worst part of their job. I know it is for me. The only thing that makes it bearable is hoping that I'll be able to engage with your ideas, or see the texts we're covering through your eyes. But if I have to stop after every sentence to figure out what you're trying to say, I'm most certainly not thinking about your ideas.

So do yourself a favor: give yourself enough time to do a good job on these papers. Remember that writing clearly takes far more time than you think it does, because you have to consider your argument from a reader's perspective, not your perspective.

I realize that the grand academic dance of submitting your work, having it evaluated, then responding to that evaluation (either through improving your work in your next paper, or by coming to see me in my office) is essentially a negotiation between us. You want to demonstrate your abilities with X amount of work, an amount that you think deserves a certain grade. You submit your work without knowing how others will see it, and only become aware of their perceptions when your work is returned to you with my comments. But this puts you at a disadvantage, because, as in any negotiation, the party that makes the first move does so blindly, and so gives up any hope of advantage.

So in the spirit of openness, let me make the first move, and try to level the playing field by giving you a few tips:

- I'll begin with a personal comment:

I know my reputation precedes me, and I know what it is, that I'm one of the closest and cruelest readers of student work in the English Department. I mark every little error. I ask condescending questions. I expect too much from you. My classroom demeanor and my grading don't match.

While I don't revel in that description, it's pretty accurate. I don't believe it's too much to ask that your subjects agree with your verbs, your tenses are consistent, and you write like you know what you're doing. Expecting anything less from you, or assuming that you can't write for an academic audience, is an insult to your intelligence and abilities. - This is academic writing, where clarity and concision are essential. If your work isn't clear, if every sentence doesn't hang together, you're losing the negotiation. What you have written may make sense to you, but it needs to make sense to your readers as well.

- At the post-secondary level, your writing isn't evaluated in terms of the amount of work you put into it. Just like any other skill, the amount of effort necessary to master academic writing varies from person to person. I am sure that it would take me far more effort than most of you to get back to playing football. But even if I did ten times the work you did, when we both showed up on the field we'd be evaluated on our skills, not on the time it took us to gain them.

- If you pay attention to what the prompt is asking you to write about, and keep that in mind as you think about your paper, you're making a good start.

- If you look at the rubric, especially the distinctions between the levels of performance in content and form, you should get a good idea of how successful your paper will be.

- If you're wondering if your "X amount of work" is enough, it isn't.

- I'll conclude with one last personal comment:

Before we had things like TurnItIn and other automatic checkers on academic integrity, I was the guy other faculty members went to to track down cases of suspected plagiarism. When Google was just getting off the ground, I was a beta tester for them (one of 25 in the country). I've also been teaching English for over 40 years now. So if you're thinking that you've changed enough of the material that you've copied and pasted to make it look like your own work, think again. If writing and evaluating papers is a negotiation, then presenting someone else's work as your own is a gamble, and you're betting your academic career that you can get away with it. I've just told you what I bring to the table, so if you really think you can get away with it, my only advice is to do it as early as possible, so you can spare yourself the work for the rest of semester, because you'll have already failed this class.

Course Work

All electronically-submitted assignments will be placed in the appropriate dropbox section or discussion forum of the Learning Management System (Folio).

I DO NOT ACCEPT LATE ASSIGNMENTS. NO EXCEPTIONS, NO EXCUSES. A late assignment is any work that is not turned in during the class period in which it is due. This means that you must anticipate any problems that will occur. In other words, a computer / printer / drive / car / arm being broken at the last minute is not an excuse. To avoid last-minute catastrophes (which always occur), DO NOT WAIT UNTIL THE LAST MINUTE TO DO YOUR WORK.

Accessibility Accommodation

In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), this course will honor requests for reasonable accommodations made by individuals with disabilities or demonstrating appropriate need for learning environment adjustments. Students must self-disclose their disability to the Student Accessibility Resource Center (SARC) before academic accommodations can be implemented.

For additional information, please call the SARC office at (912) 478-1566 on the Statesboro campus, or at (912) 344-2572 on the Armstrong and Liberty campuses.

Contingencies

Since we're an online asynchronous class, we're not really affected by things like the institution shutting down, so I'll skip right to more individual matters.

If you are under quarantine:

I can't grant you any extensions to your deadlines unless I receive a report from the GS CARES Team about your status. You can't just email me to say that you think you might have a virus and are self-isolating in order to minimize the chance of infecting others. That means that if you think you might have been exposed, or if you have tested positive, you must complete a COVID-19 Health Reporting Form, which can be found in the COVID-19 Information & Resources section of your MyGeorgiaSouthern page.

If you do have a CARES report and can't work on the class, it'll be like this class did not exist for you during your illness. If a paper is due during your quarantine, you'll have an extension until you return to class. If you miss either exam, we'll work that out on a case-by-case basis.

COURSE ASSIGNMENTS

Oxford English Dictionary Assignment

replaces the original Digital Humanities Assignment

Your first research assignment for this class will focus on an essential reference tool in literary studies, the Oxford English Dictionary. Its editors describe it thus:

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and usage of 500,000 words and phrases past and present, from across the English-speaking world.

As a historical dictionary, the OED is very different from dictionaries of current English, in which the focus is on present-day meanings. You’ll still find present-day meanings in the OED, but you’ll also find the history of individual words, sometimes from as far back as the 11th century, and of the language—traced through 3.5 million quotations, from classic literature and specialist periodicals to film scripts, song lyrics, and social media posts.

Your task in this assignment is to find a minimum of 10 words in any of the texts we've read so far that were unfamiliar to you when you first read them. Your entry for each word you select should begin with the original text where you encountered it (a line from a poem, or a sentence from a piece of fiction or drama). Next you'll copy into your entry every definition of that word in the OED. You can't just copy the definitions from that initial page that comes up when you search for the word; each of the entries on that initial page may have multiple meanings within the entry itself (see the example here, or in Folio). You'll then select the meaning you think most appropriate, and write a paragraph explaining why you think that meaning is the appropriate one. You should consider both the definition and the context within which the word was used in explaining your selection. If there are other unfamiliar usages within the definitions, you should follow those where they lead you (again, see the example).

When you look at the example, pay close attention to the notes that follow it. I've laid out the basics of MLA 9 formatting, and pointed you to a more thorough resource. Those rules aren't hard to follow; they're just very specific, and they're the way we communicate in this field. So don't wing it with your formatting, and don't think, "that's close enough." Following guidelines like these is a middle-school activity, so you should get it right. You can't plead ignorance, and you can't say it's too complicated, so consistently getting is wrong can only be a sign of lack of care, which will seriously affect your grade.

You can select words from these works:

- The "Irish History since 1850" pages (there are quite a few odd words in these pages)

- Le Fanu: Carmilla

- Yeats: "The Stolen Child" "To an Isle in the Water" "Down by the Salley Garden" "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" "When You Are Old" "Who goes with Fergus?" "To Ireland in the Coming Times" "Adam's Curse" "In Memory of Major Robert Gregory" "An Irish Airman foresees his Death" "Easter, 1916" "The Second Coming" "Leda and the Swan" "Sailing to Byzantium" "Among School Children" "Under Ben Bulben" "The Circus Animals' Desertion"

- Gregory: from Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland

- Wilde: "The Canterville Ghost"

- Synge: Riders to the Sea

- Joyce: "Araby" "The Dead"

There's only one restriction: you can't select any words I've already glossed for you, either in the texts or in class.

A final point: you should think about the corners you may wish to cut in this assignment. Your choice of words here is a reflection of your past reading history, and your ability to understand any text you read. Some of you may have a hard time finding ten words that were unfamiliar to you (and unglossed) in these texts. Others may be able to find them all in a single work. But no one will find them all in a single paragraph, or on a single page. You should want to display your abilities in their best light, so don't settle for the low-haninging fruit. If you decide to select words like "cottage" or "confiscation," you may or may not have an easier time in the OED, but you will most certainly be communicating something unfortunate about your level of reading comprehension.

Multimodal Assignment (Found Essay, Commonplace Book)

A Multimodal Essay (sometimes called a found essay or commonplace book) involves compiling and creatively arranging existing texts (including quotes or passages from various sources) to create a cohesive and meaningful narrative. It requires careful selection and arrangement of the found material to convey a specific theme or message. This assignment will require you to compose a found essay of at least 12 exhibits and then write a reflective essay (750-1000 words) describing the choices you made, why you chose them, and reflecting on the content you have curated.

Composing a Multimodal Essay:

Choose a Theme or Topic

Decide on a central theme, topic, or message you want your essay to convey. This will guide your search for relevant quotations and passages. You may want to choose a broad starting theme like place, death, fear, natural imagery, agency, or community to start with. However, I expect your theme to develop and become more focused over time.

Gather Material

Collect a diverse range of source materials that relate to your chosen theme. These materials can include quotations from books, articles, interviews, poems, song lyrics, speeches, and more. Make sure you have all the necessary bibliographic information for each source, so that you can eventually give due credit to the original authors/creators in your Works Cited page. Some of your exhibits should come from readings assigned to the class (or recommended by me) but may also include sources that relate to the material covered in class. If you’re not sure if its related, come by my office hours or email me.

Read and Select

Thoroughly read through your collected materials and identify passages, quotations, or excerpts that resonate with your theme.

Organize and Arrange

Begin arranging the selected passages in a way that creates a coherent narrative flow. You can experiment with different orders and combinations to see how they fit together best. As with any essay, you want your found essay to flow logically. This may involve arranging your exhibits topically, chronologically, or developmentally.

Create Transitions

As you arrange the passages, consider adding your own brief commentary or transitional sentences to link the found materials together. These transitions can provide context and help guide a reader through your essay.

Maintain Consistency

While the passages may come from various sources, strive for consistency in terms of tone, style, and voice. The goal is to create a unified reading experience.

Edit and Revise

Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and readability. Make sure that the arrangement of passages makes sense and effectively conveys your chosen theme.

Cite Sources

Properly attribute each exhibit to its original source. Include a Works Cited page to acknowledge the authors and works from which you've drawn the material. Follow MLA 9 guidelines for all citations.

Title and Introduction:

Choose a title that introduces the theme you're exploring. Your introduction should explain why that theme is important in 20th/21st-Century Brit Lit.

Formatting

Depending on your content, the contexts you're exploring, or your sense of appropriateness, format your essay in a way that is visually appealing and easy to read. You can use indentation, different fonts, visuals, etc. to create a strong aesthetic component.

Reflect on Your Message

Conclude your multimodal section with a reflective essay (750-1000 words) on the overarching message or insights you've drawn from the compiled passages. This essay will tie together your materials and offer your perspective on the theme. This section should be formatted as a standard academic paper according to the MLA 9 guidelines.

GRADING

OED Assignment Rubric

Your Oxfor English Dictionary assignment for this class will be evaluated according to this rubric:

| OED ASSIGNMENT RUBRIC | ||||

| Criterion | Performance for full credit | Points per item | Bonus possible? | |

| Number of words addressed | 10 | 10 points each (adding all elements below) | Y, up to + 40 points | |

| Thoroughness of OED quotation | 10 | 3/10 | Y, see above | |

| Thoroughness of your explanation | 10 | 3/10 | Y, see above | |

| Clarity of your explanation | 10 | 4/10 | Y, see above | |

| Mechanics/Usage | no errors | -1 per error | NA | |

| Formatting | no errors | -1 per error | NA | |

MM Essay Rubric

Your Multimodal Essay assignment for this class will be evaluated according to this rubric:

| MULTIMODAL ESSAY RUBRIC | |

| Criterion | Level of Performance |

| Organization | How the writer structures their text, with their purpose and their audience in mind.

|

| Significance | How the writer makes clear to their audience that each element provided supports the text’s central purpose.

|

| Multimodality | How the writer chooses multimodal elements for their essay, and how they combine those modes in a single text.

* Various sources define modes differently; these might include linguistic, aural, visual, spatial, and gestural elements; written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal elements; or any of a number of other combinations.

|

| Reflection | How the writer considers the material presented throughout this course.

|

My Grading Process (mainly for the Graduate students)

When I mark your papers, here's my process: I read your papers at least three times. The first time, I just go through them looking for your argument and if you addressed the prompt in your essay. In my next reading, I apply the following Minimum Standards Rubric, which comes from the Technical College system in South Carolina. This rubric is applied to papers from students at two-year schools, and it defines the minimum acceptable standards there. Once I've applied the Minimum Standards Rubric, I then read through your paper again, asking the questions here and evaluating it with the Essay Rubric below. This reading is where I mark your paper.

For each sentence in your paper, I ask the following questions:

- What are you saying?

At a basic level, I’m trying to decode the meaning of each sentence. If I cannot understand what you’re trying to say, everything that follows is problematic. If your sentence is confused, convoluted, or contradictory, you make it difficult, or even impossible, for me to answer this basic question. - Is what you’re saying accurate?

Does this sentence demonstrate that you understand the text or the critic you’re addressing? For instance, if you’re summarizing someone else’s argument, I need to assess if you’re being true to the original author's intent. In your response, I’m assessing your evidence and examples. - Is what you’re saying well-expressed grammatically and mechanically?

This assumes that your grammar and mechanics aren’t so bad that I’ve been stymied back up at Question #1. - Does your writing have appropriate flow?

Does each idea link up with the one before it and the one following it in a way that meets audience needs, attitudes, and knowledge?

If I can answer all four of these questions positively for every sentence, you’re doing well. But when the answer is no, complications ensue. If I can’t understand what you’re saying, I have no way to engage with your ideas, and so I have additional questions.:

- Do you not understand the original text you’re addressing?

- Do you understand the original text, but your writing leaves a gap between that understanding and what is written on the page?

EVALUATION

| OED Assignment | 20% |

| MM Assignment | 25% |

| Exam 1 | 20% |

| Exam 2 | 25% |

| Participation | 10% |

| TOTAL | 100% |