IRISH HISTORY SINCE 1850

Background

Any starting point for Irish history will be arbitrary, so let's start with one that we might all recognize: the reign of the last monarch of the House of Tudor, The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, Supreme Head of the Church of England, Astraea, Diana, Cynthia, Belphoebe, Elissa, Eliza Queen of Shepherds all, Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth Regina, or, as we know her, Elizabeth I. The 44 years and 4 months of her reign (17 November 1558 to 24 March 1603) are generally pitched as a golden age. Encyclopedia Britannica considers her reign to be "probably the most splendid age in the history of English literature, during which such writers as Sir Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Roger Ascham, Richard Hooker, Christopher Marlowe, and William Shakespeare flourished.

But not everybody was so enthusiastic about her reign. In "The Royal Image in Elizabethan Ireland," Christopher Highley demopnstrates how Elizabeth was viewed by many of her Irish subjects. Some terms their for her included:

Images of Elizabeth were burned, defaced, spit upon, torn up, or otherwise defaced. "Obscene and blasphemous portraits of Elizabeth were displayed in continental Catholic countries; throughout her reign, attempts were made to harm the queen "by stabbing, burning,or otherwise destroying her image." (65)

Even Old English Catholics in Ireland reacted to Elizabeth's fulfillment of the Tudor Conquest. William Lyon, the bishop of Cork and Ross, during his annual inspection of school books, discovered:

The Tudor Plantations

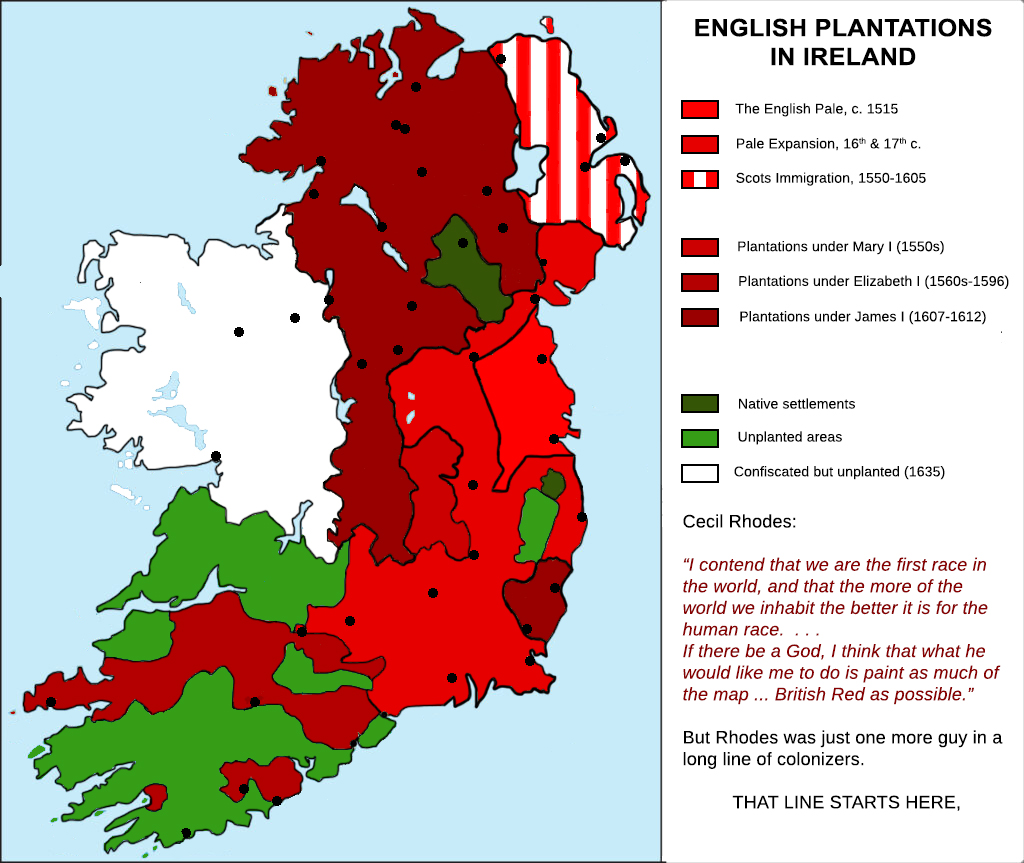

The Tudor Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland were a series of acts by the English crown that confiscated land owned by the Irish and colonized it by sending settlers from England and Scotland. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, anglicizing and "civilizing" Gaelic Ireland. The Crown simply divided the land into blocks of 12,000, 8,000, 6,000, or 4,000 acres, then bestowed that land upon "Undertakers" (wealthy English colonists who “undertook” the task of importing tenants). Their job was simple: find non-Irish tenants who would work the land. Plantation land, however, could not be leased to the Irish. The Undertakers sought out families in England and Wales who would then be shipped to Ireland.

The main plantations took place from the 1550s to the 1620s, with some failed attempts at the beginning of this time (because not enough colonists would sign on). But biggest and most successful was one of the last, the Plantation of Ulster. This Plantation involved confiscated territory being granted to new landowners on the condition that they would establish settlers as their tenants and that they would introduce English law and the Protestant religion. The estates established here were smaller, from 350 to 2,000 acres. In general, the plantations led to the founding of many towns, massive demographic, cultural and economic changes, changes in land ownership and the landscape, and also to centuries of ethnic and sectarian conflict. The Ulster Planatation, with an influx of roughly 10,000 Scots, made the most radical changes to Ireland in all the realms above.

The English have been in Ireland a long time. . . .

Here's the English-owned land in Ireland before the reign of Elizabeth I.

| Land Ownership | Area | % |

| Catholics | 32,595 miles2 | 100% |

| Protestants | 0 miles2 | 0 |

Here's English-owned land after Elizabeth and the Tudors

gave plantations to English nobles and those loyal to their house.

| Land Ownership | Area | % |

| Catholics | 2,608 miles2 | 8% |

| Protestants | 29,988 miles2 | 92% |

| TOTAL PRICE OF ALL LAND TRANSFERRED: £0 | ||

The Protestant Ascendancy

This mass confiscation of land was rounded off with Cromwell's confiscation of 2/3 of the land remaining in Catholic hands after 1640. Tens of thousands of Scots had already been given land in the north during the Ulster Plantation. Then 12,000 soldiers who served in Cromwell's army were given acreage in the midlands. These boots-on-the-ground farmers, however, weren't the ones making the real money. The members of the English aristocracy who were granted confiscated lands—those absentee landlords who lived in Britain and collected rents from their estates in Ireland—are the one who saw the real windfall. These English and Anglo-Irish families who owned most of the land, and had almost limitless power over their tenants, were at the top of the social and economic pyramid, and were known as the Ascendancy class. Some of their estates were huge: the Earl of Lucan, for example, owned over 60,000 acres. They used agents to administer their property, and many of them had no interest in it except to spend the money the rents brought in.

The Penal Laws

The rise of this new ruling class, the Protestant Ascendancy, was facilitated and formalized in the legal system after 1691 by the passing of various Penal Laws, which discriminated against the majority Irish Catholic population of the island. These laws were instituted during the last years of the 17th century and the early years of the 18th century. They were imposed on Ireland's Roman Catholic population, and enforced for over a century. At this time, Catholics on the island outnumbered Protestants by at last 5 to 1, but the Penal Laws undermined Catholic economic and political power by land confiscation. Enacted by the Irish Parliament, they were designed to maintain Protestant control and dominance by denying Irish Catholics religious freedom, education, political representation, and property rights. They reinforced the Protestant Ascendancy by concentrating property and public office in the hands of those who, as communicants of the established Church of Ireland, subscribed to the Oath of Supremacy. This Oath acknowledged the British monarch as the "supreme governor" of matters both spiritual and temporal, and abjured "all foreign jurisdictions [and] powers" — by implication both the Pope in Rome and the Stuart "Pretender" in the court of the King of France.

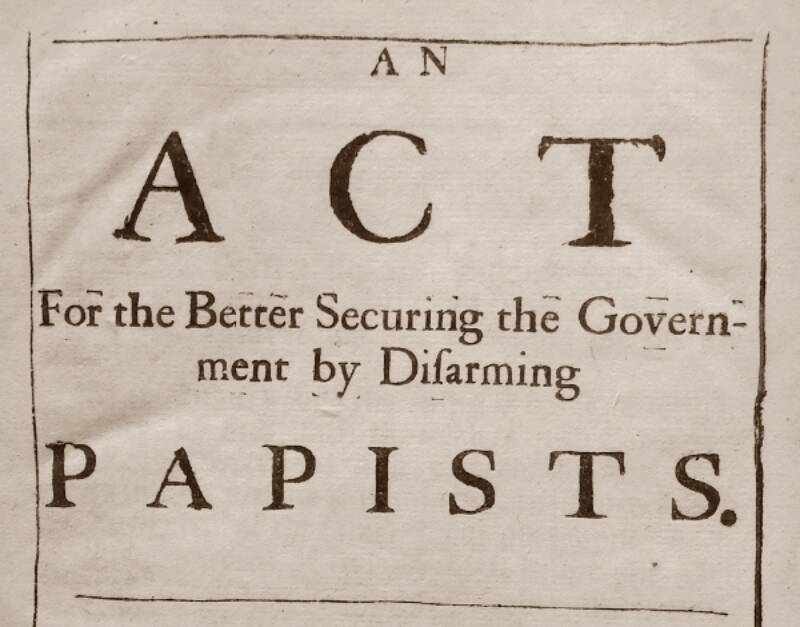

Many of these Penal Laws were on the books before 1695, but their enforcement was inconsistent. But the 1695 passage of the Settlement of Ireland Act, which declared all acts and laws made by previous Parliaments to be void, cleared the decks for a new political and economic order in Ireland. This act was accompanied by two others, An Act for the Better Securing the Government, by Disarming Papists and An Act to Restrain Foreign Education, that laid the groundwork dor the rigid, systematic, and continuopus enforcement of this body of laws for over a century.

From An Act for the Better Securing the Government, by Disarming Papists:

For preserving the public peace, and quieting the kingdom from all dangers of insurrection and rebellion for the future; be it enacted by the King's most excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal and commons in this present Parliament assembled, and by authority of the same, that all Papists within this kingdom of Ireland shall, before the first day of March next ensuing, discover and deliver up to some justice or justices of the peace, or to the mayor, bailiff, or head officer of the county, city, town corporate, or place respectively where such papist chall dwell and reside, all their arms, armour, and ammunitionof what kind soever the same be, which are in his or their hands or possession . . .

From An Act to Restrain Foreign Education:

Whereas it has been found by experience that tolerating at Papists keeping school or instructing youth in literature is one great reason of many of the natives continuing ignorant of the principles of the true religion . . no person of the Popish religion shall publicly teach school or instruct youth . . . upon pain of 20 pounds and prison for three months for every such offence . . .

A sample of the Penal Laws

- Catholics could not hold public office (Member of Parliament, Judge, Solicitor, Jurist, Barrister, Sheriff, Member of a Town Council, or Civil Servant)

- Catholics could not vote or be elected to office.

- Catholics could not buy any land.

- Catholics could not own a horse worth more than £5.Catholics could not own a horse worth more than £5.

- Catholics could not travel more than five miles from their homes.

- Catholics could not lease land for longer than 31 years, and the annual rent was equal to 2/3 of the land's value.

- Catholics could not hold arms nor be members of the armed forces.

- Catholics could not establish schools or send their children abroad for education.

- Catholics could not marry a Protestant.

- Catholics could not be an orphan’s guardian.

- Catholics could not live in many provincial towns.

- Any Protestant seeing a Catholic tenant farmer working land that, in their opinion, yielded crops worth more than 1/3 the annual rent, could enter the farm, and, by swearing to the fact of that yield, could take possession of the farm.

- Any Protestant could take the horse of a Catholic, no matter how valuable the animal was, by paying £5.

- Catholics were fined £60 if they did not attend an Anglican Church of Ireland worship service at least once each month.

- Catholics (and Dissenters) were required to pay tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland.

- Existing Catholic clergy were registered and required to take an oath of loyalty to the Anglican Church of Ireland. But those clergy considered especially dangerous, the members of the Catholic hierarchy, members of monastic communities, and all Jesuits, were exiled.

- Any Catholic priest who emigrated to Ireland was to be hanged.

The 1798 Rebellion

This was one of the largest rebellions against English rule. It was also the most threatening to the English, because, for the first time, Catholics and Protestants united against the Crown. The Society of United Irishmen, inspired by the American and French revolutions, was founded in 1791, with the first two chapters in Belfast and then in Dublin. Members were primarily middle class, but the Belfast society was mostly Presbyterian, and the Dublin society was a mix of Catholics and Protestants. Their initial objectives were minimal: suffrage for Catholics and those who did not own property. They had a determinedly non-sectarian outlook, their motto being, as their leading member Theobald Wolfe Tone put it,

under the common name of Irishman

Some of their early demands were granted by the Irish parliament. Catholics were given the right to vote in 1793, but only if they owned land worth more than 40 shillings. They were allowed to pursue higher education, obtain degrees, and serve in the military and civil service. But they still could not hold any public office or sit in Parliament.

The United Irishmen were banned and went underground in 1794. Wolfe Tone went into exile, first in America and then in France, where he lobbied for military aid for revolution in Ireland. The Society then claimed that their goal was a fully independent Irish Republic. They began organizing a clandestine military structure, working with other secret societies, both Catholic (the Defenders) and Protestant (the Peep of Day Boys and the Orange Order), to recruit more foot soldiers for the hoped-for revolution. As a result, while the majority of the United Irishmen’s top leadership remained Protestant, their foot soldiers, except in northeast Ulster, became increasingly Catholic.

In 1796 Wolfe Tone returned from France with a large fleet set on invasion, with almost 14,000 troops. But the fleet ran into a series of terrible storms, and many ships were wrecked off Bantry Bay in County Cork. iThois forced them to return to France. The government in Dublin, shocked by how close they had come to being invaded, responded with a vicious wave of repression, passing an Insurrection Act that suspended habeas corpus and other peacetime laws.

British troops, local militia, and a force that was fiercely loyalist and mostly Protestant (the Yeomanry), government forces attempted to terrorize any would-be revolutionaries in Ireland who might aid the French in the event of another invasion. The Crown forces’ methods including burning the houses of Catholics and Catholic churches, summary executions, and "pitch-capping," where tar was placed on a victim’s scalp then set on fire.

Their rebellion was supposed to begin on May 23, 1798, but the Dublin authorities became aware of their plans and arrested most of the senior United Irishmen leadership on May 22. With their leasders mostly in prison or in exile, the rising flared up in in a localized and uncoordinated manner. Large bodies of United Irishmen rose in arms in the counties around Dublin; Kildare, Wicklow, Carlow and Meath, but Dublin city itself, which was heavily garrisoned and placed under martial law, did not stir.

The only successful implementation of their plans came in County Wexford. did the United Irishmen meet with success. There the insurgents defeated some militia and Yeomanry units and took the towns of Enniscorthy and Wexford. The leadership of the Wexford rebels was both Protestant—their military leader, Harvey Bagenal—and Catholic—several Catholic priests like Father John Murphy. The majority of the fighting force was Catholic, united by their outrage at the sectarian atrocities committed in the previous months by the Yeomanry.

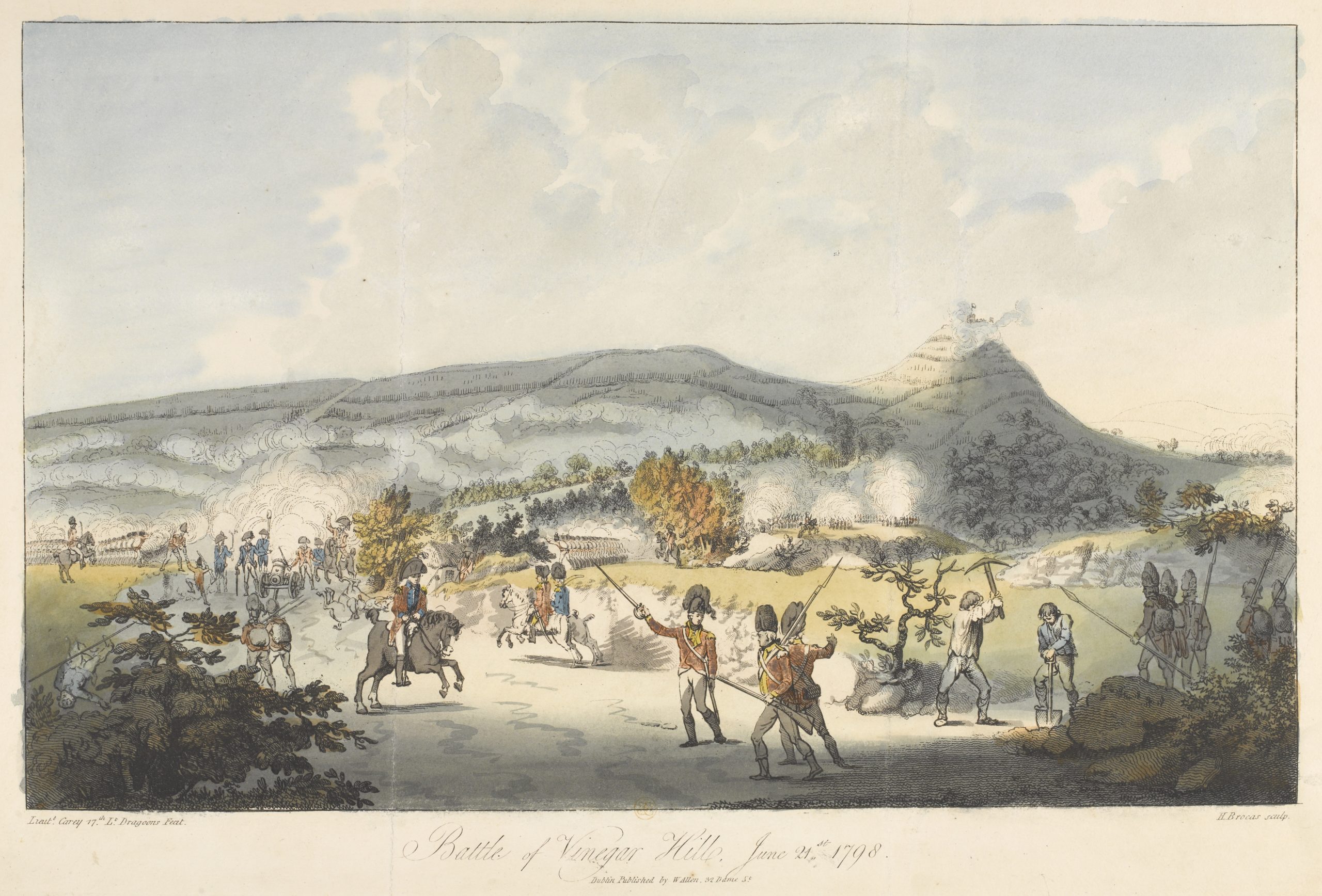

But these rebels failed to take the towns of New Ross and Arklow, despite determined and costly assaults, and remained bottled up in the southeastern corner of the island. The Wexford rebellion was smashed about a month after it broke out, when over 13,000 British troops converged on the main rebel camp at Vinegar Hill on June 21, 1798. They rained artillery on the rebels,but were not able to capture all the rebels. Some who escaped tried to spread the rebellion into County Kilkenny, and others attempted to join up with United Irishmen in counties Kildare and Meath, before finally seeking refuge in the Wicklow mountains. Guerrilla fighting continued, but the main rebel stronghold had fallen.

In the north, the mainly Presbyterian United Irishmen launched their own uprisings in counties Antrim and Down, in support of Wexford in early June. However, after some initial success, they were defeated by government troops and militia.

The main fighting in the 1798 rebellion lasted just three months, but the deaths ran into the tens of thousands. Estimates range from 10,000 to 70,000 dead rebels. Of course, thousands more were injured, and thousands of farms and homes were burned. Thousands more former rebels were exiled to Scotland or transported to penal colonies in Australia.

While the radicals of the 1790s had hoped that religious divisions in Ireland could be put aside, the fierce sectarian violence that took place on both sides during the rebellion actually hardened sectarian animosities. Many northern Presbyterians began to see the British connection as less potentially dangerous for them than an independent Ireland, where they would be a minority.

The United Irishmen’s hope of founding a secular, independent, democratic Irish Republic therefore ended in total defeat. But their foundation of the ideology of Irish republicanism would have a long and enduring legacy upon Irish politics.

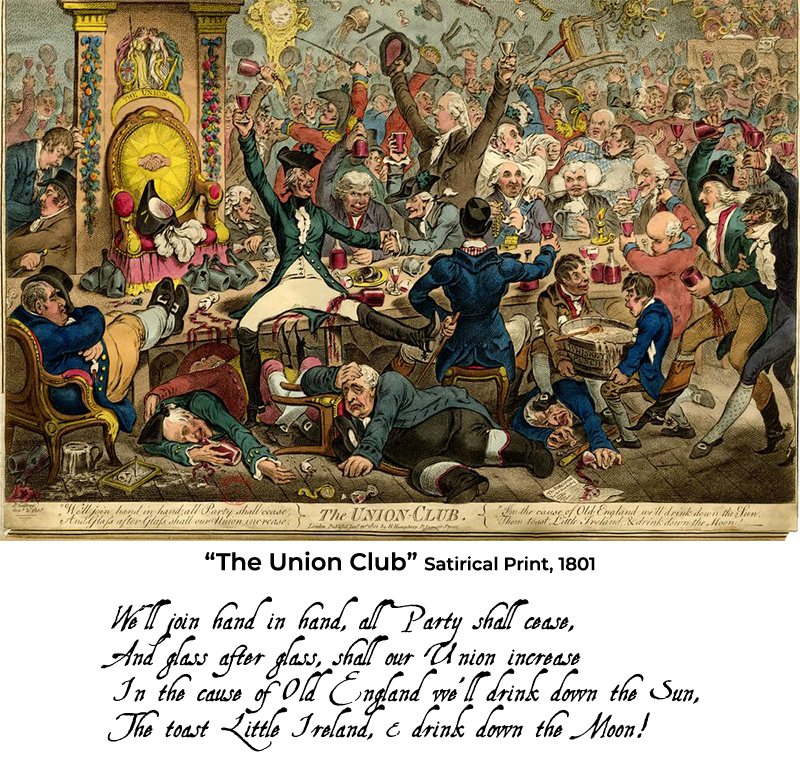

The Act of Union

The ultimate result of the 1798 Rebellion was The Act of Union, which was passed in 1800. This Act abolished the independent Irish Parliament in Dublin, and brought Irish Administration under the British Parliament. As a result, Britain and Ireland had a common King, Parliament, army and flag. Union had always been distrusted and disliked. It was only brought about after enormous expense and much bribery. Ironically, the Act of Union led to the resignation of one of its finest supporters: William Pitt, the Prime Minister of England. Pitt decided to solve the troubles in Ireland by proposing Parliamentary union with England, coupled with Catholic emancipation. The Irish Protestant Parliament was recalcitrant, but pressure from Dublin Castle, combined with a wholesale distribution of honors, places, and pensions, soon brought about a change of heart.

Pitt intended the Act of Union to be accompanied by relief to Catholics from paying tithes to support the Anglican Church in Ireland, state payment of salaries to the Irish Catholic priesthood and, above all, Catholic emancipation, allowing Catholics to sit in Parliament. But King George III refused to accept this, insisting that Catholic emancipation would violate the terms of his Coronation Oath, by which he had sworn to maintain the privileges of the Anglican Church. Finally, rather than break a pledge, Pitt resigned in 1801. The way in which union had been brought about left Ireland betrayed and resentful.

Farmers, Cottiers, and Strong Farmers

Ireland at this time had a very unbalanced social structure. Farmers rented the land they worked, and those who could afford to rent large farms would break up some of the land into smaller plots. These were leased to "cottiers" or small farmers, under a system called "conacre." Nobody had security or tenure and rents were high. Very little cash was used in the economy. The cottier paid his rent by working for his landlord, and he could rear a pig to sell for the small amount of cash he might need to buy clothes or other necessary goods.

There was also a large population of agricultural laborers who travelled around looking for work. They were very badly off because not many Irish farmers could afford to hire them. In 1835, an inquiry found that over 2,000,000 people were without regular employment of any kind. Under the Irish Poor Law of 1838, workhouses were built throughout the country and financed by local taxpayers.