IRISH HISTORY SINCE 1850

2. An Gorta Mór

3. The Land League

4. Parnell and Home Rule

5. Unionism

6. The Cultural Revival

7. Home Rule

8. The Easter Rebellion

9. The War of Independence

10. The Free State: '20s

11. The Free State: '30s

12. The Troubles: '60s & '70s

13. The Troubles: '80s & '90s

14. The Celtic Tiger

15. Death of the Tiger

16. Sources

The Land League

The issue of land ownership was central to political life in Ireland in the later decades of the nineteenth century. It was clearly understood that the ways in which Irish land was owned, rented out, and inherited had contributed to the appalling effects of the famine. The question was how could the situation be rectified.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, before a solution could be found, another series of bad harvests and the threat of famine again hung over Ireland. The landlords, who believed that their tenants would not be able to pay their rents in a time of poor harvest, began evicting them from the land. In response, a new movement, the Irish National Land League, emerged to fight for the rights of small tenant farmers. The goal of this movement was to bring about a more equitable system of land ownership. The League wanted three main things:

- Fair rent in line with the market price for land, rather than an inflated charge set by the landlord.

- Fixity of tenure. The League wanted rent agreements to state how long tenants could stay on the land rather than leave them with no security.

- Freedom of sale. The tenants had no rights over the land when it was sold — they wanted to have a say.

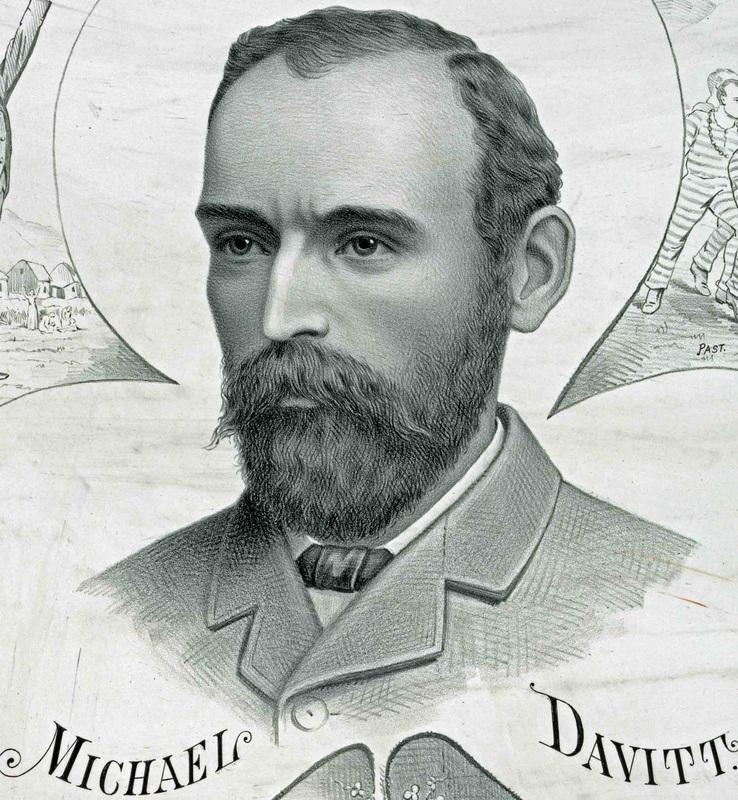

founder of the Irish National Land League

More broadly it wanted to get Irish land into the hands of Irish small farmers and away from the ownership of absentee landlords who didn't care for their tenants' welfare.

The founder of the Irish National Land League was Michael Davitt. His family had been evicted from their land in the 1840s and forced to emigrate to England. Davitt was sent to work at the local cotton mill in Lancashire. Like many other young boys, he was working in dangerous conditions. At eleven he lost his arm in an accident, and was unemployable. He educated himself, and began seeing the British as being responsible for all of Ireland's problems. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 1870 for Fenian activity, but released in 1877. On his release he turned his attention to the landlords, whom he saw as the root of all evil in his native land.

To achieve its aims the Land League attacked the landlords who treated their tenants badly, who charged unfair rents, and who evicted their tenants. Many of these attacks took a physical form, and landlords and their families were beaten. Some, such as Lord Leitrim (a landlord who was notorious for his poor treatment of tenants), were killed.

The greatest tool of the Land League, however, was the boycott. The basic idea was that people would stop doing business or socializing with landlords whom they opposed because of their unfair practices. Farmers would refuse to work for them, and the rest of the community was encouraged to ostracize the guilty party. One of the first targets was Captain Charles Boycott, of Lough Mask House, County Mayo, after whom this strategy was named. The Land League didn't boycott only the landlords, however. They also boycotted those Irish people who chose to take on the land from which others had been evicted. In one speech, the President of the Land League told the crowd that anyone who had taken on the land of the evicted should be:

- Ignored on the roadside when they were seen.

- Ignored when met at the shop counter.

- Ignored at the fair and marketplace.

- Ignored in the house of worship.

The Land League was so effective that the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, decided to do something about the situation. Rather than squash the protests, he made the decision to actually address the issues. Gladstone's Land Act (which was agreed by parliament in 1870) began a process by which the old landlords were steadily replaced by Irish owners of the land. The process has been called "a social revolution which transformed Ireland." The Land Act finally gave Irish tenants what they had wanted: fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale of a tenant's interest.

To stop the disruption caused by the Land League's tactics, Gladstone first restored some kind of order to Ireland by clamping down on the League's activities by passing a series of coercion acts that tried to prevent political activism. However, while the Act was quite revolutionary, it did have shortcomings. Tenants who already owed rent were not covered by the new law, nor were leaseholders. As a result, Land League activity continued, and the Land League initially boycotted the act and told their followers not to pay their rents.

This was a period when demands for some kind of Irish self-determination were becoming very popular. Politicians, the press, and the people began to link the land issue with the question of Ireland's relationship with Britain. Was it possible to solve the land question without also addressing the issue of self-determination? Because of this link between the two questions, the agitation over the land issue became one that was heavily influenced by ideas of Irish nationalism.

Everyone understood that the land ownership question was a key cause of complaint by the Irish. The British general election of 1880 had been fought over the issue, and many commentators also picked up the question. One nationalist even said: "Damn Home Rule! What we're out for is the land. The land matters. All the rest is talk."

Opinions differed greatly in Britain about what to do with Ireland. The Liberals argued that Irish demands should be met, whereas the Conservatives thought that the Irish should not be allowed to be so lawless in the pursuit of their goals. Some historians have argued that land reform was the best option, as it calmed the situation and prevented a revolutionary movement that violently linked the land issue with national freedom. Others have argued that the British, by enacting land reform, deliberately sought to divert Irish attention away from their aspiration for political freedom.