IRISH HISTORY SINCE 1850

Home Rule

of the 1898 centenary

In 1898 huge celebrations were held across Ireland to mark the centenary of Wolfe Tone's rebellion. These events brought together various strands of nationalism in Irish life, and allowed for a very public display of the enthusiasm for an independent Ireland. At the turn of the century there was a renewed interest in the idea of Irish nationalism. The nationalist spirit had never gone away, but because of the split following the fall of Parnell, its voice and focus had been lost. The 1898 celebrations encouraged people to begin voicing their demands for independence.

In this atmosphere, the Home Rulers finally managed to put aside their arguments, and pulled themselves together. In the mid-1890s, William O'Brien had formed the United Irish Land League in Mayo. The League was brought together to fight for the rights of smallholders in the West of Ireland (and proved that no matter how far reaching the government land reforms, more was always needed). O'Brien also had another agenda. He understood that the land issue had always been central to Irish politics and a point of consensus and he aimed to use the League to bring the Home Rulers together around an old point of agreement.

In 1900 the League was formally integrated into the Home Rule party, and a popular dimension restored. No longer was Home Rule politics to be dominated by political infighting amongst its leaders — it had real work to do. Later the same year, John Redmond was elected to the Chair of a reunited party. By virtue of the League's popularity, and its ability to refocus everyone on the real issues, rather than the legacy of Parnell, the Home Rule movement came back together. The real question was whether the damage of the split would hamper it as a political force.

Although the Home Rulers had got back together, there was still a lot of bad blood. Not only did the party fail to forget all the animosity that surrounded the Parnell split, but during the period of division a host of strong and opinionated men had risen to the fore. Redmond's leadership of the party has been called by one historian, "at best, a balancing act." In many ways he was more like a juggler, trying to keep all the different demands and pressures in the air without dropping anything. One half of his party expected him to be aggressive, and to challenge the British government at every turn, while the other encouraged him to accept reforms such as the Land Purchase Act without criticism, and to consider them as positive actions. While the Conservatives were in office, and maintaining their hostility to any talk of Home Rule, there was little he could do anyway.

Redmond had a series of problems in trying to stamp his authority on the Home Rule movement:

- He believed in doing things the "right" way, or as a contemporary said of him, he had a "prejudice in favor of the truth that was almost English." As a result Redmond was committed to strictly parliamentary means for most of his career, and did not build the broader nationalist coalition that Parnell managed to bring together.

- Other main figures in the party, who had been active during the period of the Parnell split and perhaps imagined themselves as the leaders of the Home Rule Movement, such as James Dillon and William O'Brien, while accepting him as leader, spent a lot of time publicly criticizing him and offering alternative suggestions — not good for party cohesion.

- Although small in scale, a nationalist alternative, in the shape of Sinn Fein emerged in 1907 to challenge the Home Rule agenda. By 1918 they overtook the Home Rulers in terms of popular appeal.

While the Conservatives were in power, and trying to kill Home Rule with kindness, Redmond could only have a limited impact on politics at Westminster.

Redmond had to keep this difficult juggling act up for some time as he had no real power in Parliament until the election of 1910 when, despite their confidence, the Liberals only managed a two-seat majority. Suddenly Redmond was the king maker. He promised the Liberal leader, Asquith, his support in whatever he wanted, so long as an Irish Home Rule bill was brought before parliament. The problem Asquith faced, as had reformists in British history before him, was that the House of Lords didn't really appreciate reform, and had an annoying habit of blocking anything that they didn't like as they could hold bills back and sometimes veto them. Asquith decided to act. He went to the country in a second election in 1910 with this simple agenda: If elected, Asquith and the Liberals would curtail the powers of the House of Lords to veto bills from the Commons; instead, the Lords would only be able to delay a bill for two years. The electorate supported the Liberals and Asquith was able to convince the Lords that their day had passed.

Asquith and the Liberals were more interested in their own agenda than that of Home Rule. The House of Lords had rejected the Liberal Party's reforming budget in 1909, so the 1910 election had been fought on the issue of the powers of the Lords. Having won the popular vote (just), Asquith announced a plan to limit the powers of the House of Lords, threatening to create enough new pro-reform peers to swamp any opposition. The resulting Parliament Act, passed in August 1911, ended the Lords' veto over financial legislation passed by the House of Commons. This in turn paved the way for the passage of the Home Rule Bill through the Lords in 1912.

In 1912, and true to his word, Asquith placed a Home Rule bill before parliament. Redmond and the Home Rulers would get their reward. After much acrimony, vicious debate, and aggressive campaigning against the bill by unionists, the bill was passed in the Commons. The bill was unsuccessful in the Lords, but as they no longer had a veto, the bill would only be delayed for two years. Home Rule would become a reality on 18 September 1914. The Irish rejoiced. Many people thought that Redmond had delivered to Ireland what it had always wanted: Home Rule. But in the months before the outbreak of the First World War, the government watered down the proposals. Redmond was convinced that he should allow the six counties of Ulster with majority Protestant populations to be excluded from the Home Rule Act for six years. So while Redmond had won Ireland its independence, he quickly allowed parts of it to opt out because of the power of the unionists within British politics. Had Redmond achieved freedom for Ireland, or had he been outmaneuvered by a combination of unionist and British politicians? Some historians feel that Redmond had put too much trust in the British political system and was duped by more powerful forces, while others think that he got the best deal he could.

"Home Rule" banner while bulldogs with heads of Edward Carson,

Bonar Law and Lord Londonderry strain at the leash.

Nationalists v. Unionists

The Home Rule Bill, which created an independent Irish parliament, had been passed by the British parliament in 1912 and was due to be enacted in 1914. Under this bill, Ireland would have its own parliament, but certain big issues, such as foreign policy, would remain in the hands of the parliament in London. Ireland would also remain a full member of the British Empire. This was a form of self-government that worked wholly within the constitutional sphere, and did not create a separate Irish state that was in any way a Republic.

Constitutional nationalism, in the form of John Redmond's Irish Parliamentary Party, was not the only nationalist force in Ireland, however. Other nationalist forces, including such groups as Sinn Fein and the Irish Republican Brotherhood, existed outside of Parliament and pursued their own ends. In addition to the various nationalist groups were the unionists — those who opposed the idea of Home Rule altogether.

This crowded political landscape meant that the pressures on the custodians of constitutional politics were huge. If any concessions were made in the passage of the Home Rule Bill, or if the unionists took military action to prevent the enactment of Home Rule, then a welter of political, and armed, opposition would be unleashed. In short, Ireland was becoming increasingly restless and difficult to manage. And this situation was happening at the same time that German intentions in Europe were becoming increasingly troublesome.

The Advanced Nationalists

It was clear to many nationalists that the unionist population, those who wished Ireland to remain part of Britain, would not meekly accept Home Rule. Sinn Fein and other nationalist movements that existed outside of parliament understood this and readied themselves for action. The various groups, often referred to as advanced nationalists, and their agendas were as follows:

- Sinn Fein: Meaning "ourselves alone", Sinn Fein had been formed in 1907 by Arthur Griffith. This party offered a more radical reading of the Irish-British relationship. Rather than accepting continued British involvement in Irish affairs and membership of the Empire, as would be enshrined in the Home Rule Bill, Sinn Fein argued for complete and total independence from Britain. Initially the party did not advocate the use of violence to achieve its aims. Sinn Fein was always a fringe political movement until after the Easter Rising of 1916 when it rose to electoral prominence.

- Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB): The IRB was a secret movement advocating physical force for the purpose of creating an Irish Republic and drawing its inspiration from the fenians of the nineteenth century. The IRB believed in the use of violence to attain its aims. While ideologically highly committed, the IRB's membership only numbered some 2,000.

- The Irish Volunteers: Formed in 1913 by Eoin MacNeill, the Volunteers were a direct response to the formation of armed groups in Ulster that would oppose Home Rule by force. The Volunteers aim was to guarantee the rights and liberties of Irish people. By the outbreak of the First World War the estimated membership of the Volunteers was 180,000.

- The Irish Citizen Army (ICA): The ICA was formed in 1914 as a socialist worker's army. Although committed to the ultimate creation of a socialist state in Ireland, the ICA acknowledged that, without independence from Britain, the workers' republic it dreamt of could not be achieved.

- Cumann na mBan: Meaning the "Association of Women", Cumann na mBan emerged from the suffragette struggle. Its aim was to assist in the arming, equipping, and support of Irishmen in the defense of Ireland.

Although the advanced nationalists, with the exception of the Irish Volunteers, lacked mass support from the Irish populace, they were not without funds and resources. Many Irish-Americans believed vehemently in the complete rejection of British rule in Ireland, and were content to fund movements that were dedicated to that goal. American money was used to support the political campaigns of the advanced nationalists, and from 1914, these funds were regularly used to secure arms and ammunition.

The Unionists and the Ulster Volunteer Force

Unionists were appalled by the idea of Home Rule for Ireland, and believed that their way of life, economic security, and their very safety was under threat from the idea of a nationalist and Catholic dominated Ireland. In 1914 the Ulster Volunteer Force was formed by the unionist leaders Edward Carson and Sir James Craig to defend the union by force if necessary. By 1915 the police estimated that the Force had some 53,000 rifles in its possession and a membership of 100,000. Seen primarily as a force for the defense of unionism, the Ulster Volunteer Force was popular amongst the majority of unionists.

Civil War Looms

As the date for the enactment of Home Rule edged ever nearer, it became clear that the unionists would not meekly accept their fate. They would, through the force of the Ulster Volunteer Force, fight against the creation of an independent Ireland. Ranged against the unionists were the various nationalists groups, listed in the preceding section, who would equally take up arms to ensure that Home Rule did become a reality.

The mood in Ireland at the time was ominously reflected in two speeches in 1914. In January 1914, the Conservative Andrew Bonar Law made clear his belief that Ireland was "drifting inevitably to civil war" and that Home Rule would be resisted "by force if necessary." In July, the king acknowledged that "the cry of civil war is on the lips of the most responsible and sober minded of my people." Ireland was, in the summer of 1914, undoubtedly on the verge of a major conflict.

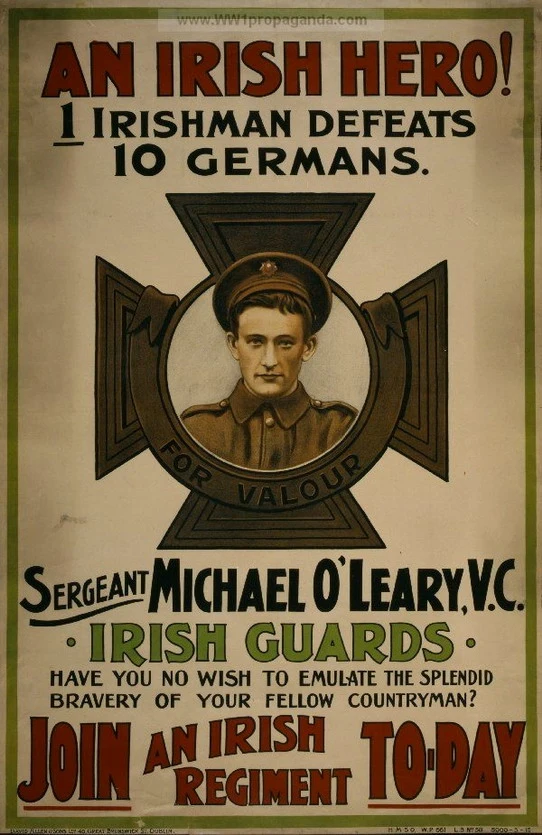

for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded

in the British military). He single-handedly charged and destroyed

two German barricades defended by machine gun positions

near the French village of Cuinchy.

World War I

For Irish nationalists at least, 1914 should have been a great year. The self-government they had so long dreamt of was due to be enacted in September and they would have control over their own affairs. It was clear early on that the party would be dampened by the opposition from unionists; after all, opposition from unionists, especially the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force, was solid, and it was clear that they would not stand idly by when the Bill was enacted. The forces of nationalism, particularly the Irish Volunteers, were prepared to take up arms against unionist intransigence and would, in all likelihood, be supported by the forces of advanced nationalism who would use any struggle to promote their own agenda. But then, in August, one month shy of Home Rule being enacted, the Germans gate-crashed the party and the whole thing was called off.

For the British the situation was a complete nightmare. As storm clouds gathered in Europe and a war against Germany became a possibility, they didn't know what would happen in Ireland. Would events there spiral out of control and undermine the war effort, or would the various groups in Ireland postpone their struggles for the greater good?

The arrival of WWI in the summer of 1914 allowed all the problematic permutations of what might happen in Ireland to be shelved. There was a war to be fought in Europe, and everyone was briefly off the hook. In all likelihood the outbreak of the First World War prevented a potential civil war in Ireland between unionists and nationalists. The avoidance of such a struggle was desirable, but events during the 1914--18 conflict changed the political landscape in Ireland, and led to the ascendancy of radically minded and non-constitutional forces. If the World War had not happened, the British would have been forced to involve themselves in the support of the Home Rule as it had been drafted in 1912. The British declaration of war on Germany in August 1914 caused the Home Rule Bill to be suspended until the conflict was over.

The struggle on the Western Front postponed the struggles in Ireland between unionists and nationalists, but how did the Irish, unionist and nationalist, react to the War against Germany? The positions that the various groups took up were:

- The Unionists, who saw themselves as integral parts of Britain and Empire, fully supported the war effort. The Ulster Volunteer Force became the bedrock of the 36th (Ulster) Division as a unit in the British Army. The 36th were allowed to retain their distinctive unionist identity, and their uniforms featured the recognizable insignia of Ulster.

- The nationalists, led by Redmond, also threw their weight behind the war. Redmond argued that the war against Germany was a struggle for Ireland as much as it was for Britain, and that nationalists should take part to defend their own freedoms. Although the Volunteers, numbering some 170,000, were offered to the British army, they were not granted their own division in the same way as the unionists.

- The advanced nationalists, led by Sinn Fein, opposed the war as an imperial struggle in which Ireland had no part. They called for Irish men to leave the Volunteers and join a new force, the Irish or Sinn Fein Volunteers, whose role would be to defend Ireland in the face of aggression from any nation. By 1915, only 11,000 men had answered that call.

Unlike the rest of Britain, Ireland, whether unionist or nationalist, was never subject to conscription of its men into the armed forces. This meant that all Irishmen who fought in the war, including the thousands that died, were volunteers. The British believed that enforcing conscription in Ireland would be too difficult. When the idea was mooted in the spring of 1918 the chief secretary of Ireland informed the cabinet that they "might almost as well conscript Germans." The attempt to introduce conscription in 1918 had profound effects and contributed to the rise of Sinn Fein.

Ireland suffered greatly during the war. As a rough estimate some 35,000 of the 140,000 men who volunteered to fight were killed. For the unionists the sacrifice was most marked on the first day of the Battle of the Somme when the 36th (Ulster) Division went into action. Their numbers were decimated by the Germans, and the sacrifice is annually marked in Ulster on July 1 each year.