IRISH HISTORY SINCE 1850

Death of the Tiger

In the 1990s, sensible policies and a benign global economy helped Ireland catch up with its European neighbors that for decades had left it languishing. Between 1993 and 2000 average annual GDP growth approached 10%. But then someone put speed in the tiger's water. Over the decade, the boom turned bubbly, as low interest rates and reckless lending, abetted by dozy regulation, pushed up land values and caused Ireland to turn into a nation of property developers. In County Leitrim, in the Irish Midlands, housing construction outstripped demand (based on population growth) by 401% between 2006 and 2009, according to one estimate.

Few minded. The Irish became, by one measure, the second-richest people in the European Union. "The boom is getting boomier," said Bertie Ahern, Ireland's taoiseach (prime minister), in 2006. The government began exporting the Celtic Tiger model, telling other small countries that they, too, could enjoy double-digit growth rates if they followed Ireland's lead. People splashed out on foreign holidays, new cars and expensive meals. "We behaved like a poor person who had won the lottery," says Nikki Evans, a businesswoman.

Then it all began to go wrong. Property prices started sliding in 2006-07, leaving the banks hopelessly exposed. "What happened in Ireland was very boring," says Morgan Kelly, an economist at University College, Dublin, and one of the few observers to have predicted the crash. "There were no complex derivatives or shadow banking systems. This was a good old 19th-century, or even 17th-century, banking collapse." On September 15th 2008 Lehman Brothers tumbled, sending a giant tremor round the world. Two weeks later, with the share prices of Irish banks in free fall, the government took the fateful decision to guarantee liabilities worth €400 billion ($572 billion) at six financial institutions.

The costs of the rescue mounted as the banks' losses grew, springing a giant hole in the public finances. The banking crisis had become a sovereign-debt crisis. International investors began to target Ireland as a weak link in the euro zone, raising its borrowing costs to unsustainable levels. In November 2010 it became the second country in the euro zone, after Greece, to accept a bail-out from the EU and the IMF.

"I can't tell you how depressing it is here now," says Anne Enright, a novelist. An austerity budget pushed through to meet the terms of the €85 billion bail-out is starting to hit pockets. Unemployment has shot up to 13.4%, wages have fallen and, after a peak-to-trough contraction of 14% of GDP, the economy is still flatlining. "It's very demoralizing that this thing has happened when we thought we had arrived at a modern industrialised society," says David Begg, general secretary of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions.

The Myths Of Success

Not everyone welcomed the changes that prosperity brought. Kevin Barry, a writer who had been living abroad, returned home to find that "people only spoke about two things: property prices and commuting times. It was extremely boring." Ms Evans, who runs PerfectCard, a pre-paid debit-card business, saw some of her younger staff acquire a sense of entitlement which made them hard to motivate. (It's easier now, she says.)

As Ireland grew richer, one form of exceptionalism — the fatalistic belief that Ireland was destined always to be western Europe's poor outpost — gave way to another: the myth of the Celtic Tiger. "We're very narcissistic," says Ms Enright. "We believed our boom was better than anyone else's." The twin articles of independent Ireland's faith, Catholicism and nationalism, were eclipsed by material ambition: the desire to get on, to improve one's station in life. "People lost interest in the other world while they were so successful in this one," says Mark Patrick Hederman, abbot of Glenstal Abbey, near Limerick.

The new Ireland looked attractive to outsiders. When the country opened itself to new EU members after the 2004 eastward expansion, Poles and others poured in looking for work. Rather than resenting the newcomers, many Irish were proud that their country had become a place people wanted to enter rather than leave. "The country was welcoming, open, easy-going," says Monika Sapielak, a Pole who began to visit in 2001 and who now runs a contemporary-arts centre in Dublin. "There was a sense that anything was possible." Not any more.

The first casualty of the downturn was Fianna Fail, the party that presided over the "boomier" years and, in coalition with the Greens, the subsequent crash. In a general election on February 25 2012, voters booted the party out in favor of Fine Gael and the Labour Party.

Fianna Fail is the "natural" party of government in Ireland: it has been in power for three out of every four years since winning a landslide victory in 1932, and it has been the biggest party in parliament ever since. Yet it is hard to detect a whiff of revolution. The current government is led by Fine Gael (in coalition with Labour), a party with a centre-right platform not obviously distinct from Fianna Fail's. (In Ireland's peculiar politics, the difference between the two main parties dates from the 1922 civil war, fought over the terms of independence from the British.) Few believe the party would have been a more responsible steward of the Celtic Tiger.

Retribution?

As a small country, Ireland is a hard place to hide in. Reports abound of disgraced bankers being hounded out of pubs by burned investors, or Fianna Fail candidates having dogs set on them. "There aren't that many strangers in Ireland," says Ruairi Quinn, a Labour frontbencher. This, some say, acts as a safety valve, allowing citizens to vent their anger directly rather than take to the streets.

But it also lends Irish politics an oddly intimate flavour. National candidates tout achievements that in other countries would be considered the domain of local councillors. This goes along with a proportional voting system that forces candidates of the same party to compete for votes, turning elections into intensely personal contests. "If you're not seen to be helping your constituents, you will not be re-elected," says Martin Ferris, Sinn Fein TD (member of parliament) for Kerry North.

During a windy canvassing session in a middle-class area of Tralee, County Kerry's largest town, many voters say they will back Mr Ferris because they remember how, seven years ago, he worked to improve access to local footpaths and tackle anti-social behaviour. Not one mentions his party's policies. You would expect this lot to be Fine Gael supporters, says a party worker, who appears to know them all personally. But Mr Ferris has won them round. She herself began canvassing for him because of his community work.

A TD working the campaign trail looks like democracy in action. But there are problems. Ambitious types do not want to spend their careers promising to fill in potholes and deliver passports, so they avoid politics. Moreover, the endless focus on local issues distracts from the business of running the country. "Politicians say, 'Elect me and I'll get you a swimming pool.' You'll get your pool, but there won't be any money to run it," says Damian Loscher of Ipsos MRBI, a market-research agency.

The radical transformation of Ireland into a globalised economy left some old attitudes untouched. Voters continued to tolerate levels of misbehaviour and, in some cases, outright corruption in their politicians that in other countries would have ended careers. Cronyism flourished, as businessmen, politicians and bankers sealed themselves off in a cosy world of golf matches, fine dining and the Fianna Fail tent at the Galway races. "It felt like an old boys' club," says Ms Evans—who had to use personal contacts, too, to get the government's attention.

Fond, But Not In Love

When the EU and IMF delegations arrived in Dublin for bail-out talks in November 2010, the Irish Times ran a lachrymose editorial asking if this was what the national heroes of the 1916 Easter Rising had died for. Outsiders saw this as a sign of resentment from a proud nation that was once again having its affairs run by foreigners. Yet the editorial went on: "The true ignominy . . . is that we ourselves have squandered [our sovereignty]." Having seen their leaders make such a mess of things, most Irish welcomed the arrival of technocrats.

Still, one long-term effect of this crisis has been a cooling of Ireland's love affair with the EU. When the country joined what was then the European Economic Community in 1973, children danced in the streets. Agricultural subsidies and infrastructure funding flooded in from Brussels. Equal membership in a club of nations was a seal of sovereignty. Ireland was certainly more positive about the EU than most other members. But the Irish began to suspect that the "solidarity" they heard so much about from European leaders didn't apply to their troubled economy.

The terms of the European element of the bail-out aroused particular ire. There was something approaching a consensus in Ireland that the country rescued Europe (specifically, German and French investors that had lent heavily to Irish banks) in November 2010, rather than the other way around. There were heated exchanges between Irish and EU politicians over how to apportion the blame for Ireland's crash. Some compared Ireland's bank guarantee unfavourably with Iceland's decision, after a similar meltdown in October 2008, to let the banks fail, creditors be damned.

Ireland was not about to adopt the Euroscepticism of its larger neighbor, Britain. But it did become more pragmatic. The Irish government fought hard for permission to impose bank losses on creditors not covered by the 2008 guarantee (something the European Central Bank rejected during the bail-out negotiations). "The attitude has shifted from 'We want to be part of Europe' to 'We need to be part of Europe'," said Mr Loscher.

The New Emigration

There was a growing fear that a number of young people would not be part of Europe at all. Lack of prospects would drive them to America, Canada or Australia. For at least 150 years, emigration was the instinctive Irish response to hardship. Alan Barrett of the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), a Dublin-based research body, said emigration is to the Irish what inflation is to the Germans: a trauma formed by economic wounds inflicted decades ago that still runs deep in the collective memory. The generation that came of age in the Celtic Tiger years was the first that did not feel it had to move abroad to thrive. But those days were over.

A report by the ESRI, based on employment forecasts, estimated that a net 100,000 people would leave Ireland between 2010 and 2012. That is a lot: at its peak, the net annual outflow in the 1980s was 44,000. Work-placement and visa-assistance companies advertised widely. Election candidates reported that emigration was a big issue on the doorstep.

Still, many argued that a population willing to move to where the jobs are is exactly what a country in Ireland's predicament needed. Historically, labor mobility has helped to keep a lid on unemployment. And there have been other benefits: the diaspora, particularly in the United States, has proved a useful asset for Ireland, politically as well as economically. Moreover, a move abroad today is hardly the one-way ticket it was for many in the 19th century. When Ireland started to boom in the 1990s many émigrés returned home, bringing with them much-needed skills and capital.

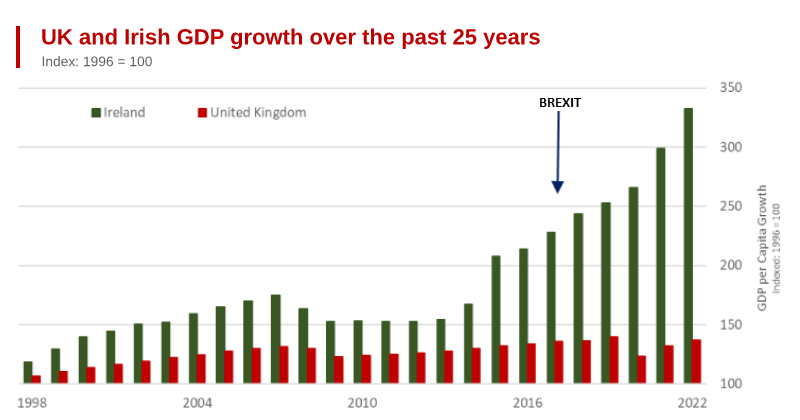

Meanwhile, the Brits have been hoodwinked by their upper classes.

The Dead Tiger, Resurrected

100 years after the Easter Rising, Ireland found itself struggling again. Some feared that the crash has shown the Celtic Tiger to have been a phantom, an illusionist's trick that distracted Ireland from its underlying poverty with glitzy cars and big houses.

Doomsayers were pronouncing prayers over the grave of Ireland's economy after the 2008 economic crash. They turned out to be wrong. Aligning with the EU, and staying there, was the best thing Ireland could have done. Look at what's happened to their former colonizers since they decided to leave.

Meanwhile, Ireland Moves

The battle for LGBT rights in Ireland has had many significant moments, with the decriminalisation of homosexuality and the Gender Recognition Act among them. None though, was perhaps as impactful on a global level as the May 2015 vote in favor of same-sex marriage. The decisive referendum result saw 62% of voters back the amendment, while 38% voted against it. It made Ireland the first country in the world to make same-sex marriage legal by popular vote.

(Prime Minister) not just once, but twice.

The Republic’s vote was preceded by a difficult personal debate that saw gay people speak about their own lives and others joining in with the campaign. Ireland's Health Minister, Leo Varadkar (who later served as Taoiseach from 2017 to 2020 and from 2022 to 2024), may have swayed the referendum when he came out publicly:

It’s not something that defines me, I’m not a half-Indian politician or a doctor politician, I’m not a gay politician for that matter, it’s just part of who I am.

BTW, Varadkar has a special connection with Georgia Southern.

And that wasn't the only big cultural move for the island. Pope Francis visted Ireland in 2018. It was the first by a pontiff since the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1979. In the intervening 40 years, Ireland had confronted its painful history of clerical abuse and the influence of the church had waned hugely. Half a million people had signed up to attend the Pope's mass in Phoenix Park outside Dublin. Estimates put the crowd at closer to 150,000. The Irish media also publicly criticized Francis’ keynote speech in Dublin Castle on the first day of his visit, when he did not make a direct apology to victims.

For a country Joyce called "priest-ridden, God-Forsaken," to move so boldly away from centuries of undue influence seemed like a true sign of growth.