IRISH HISTORY SINCE 1850

Building the Free Irish State in the 1920s

One of the great joys of having a new country is that you get to do things your way. For the government of the Irish Free State, they had the opportunity of making a new state. They could develop it as they wished, and let the whole world know what it would mean to be Irish in the new Free State.

First, they had to make decisions on everything involved in running a country: what form of government they would have, whether their police force would be armed or unarmed, what the national anthem would be, what kind of currency they'd use, and so on. If that wasn't enough, because of the Civil War, not everyone in Ireland actually agreed with the idea of the Free State, and so controlling that faction became an issue, too. Also, there was the Protestant minority that remained. Many of them remained in the civil service jobs they had previously occupied, landowners stayed on their estates, and the Protestant working class communities of Dublin and Cork carried on in their old jobs.

The first party to govern the newly independent Ireland came from the pro-Treaty side of the Civil War. They organized themselves under the name Cumann na nGaedhal ("the League of the Gaels"), and were led by W.T. Cosgrave. The opposition from the Civil War period, Sinn Fein, refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new Free State and abstained from parliament. (Many of its leading members were still in prison anyway because of their part in the Civil War.) Effectively, Cumann na nGaedheal ran a one party state, and could get on with the business of government without worrying about a sizeable parliamentary opposition.

Cumann na nGaedheal stayed in office from 1922 to 1932. In that decade they organized the mechanisms of government, law and order, and finance that are essential to any nation. Their main acts were:

- Produced the first national constitution in 1922.

- Worked within the terms of the Treaty of 1921 and established good working relationships with Britain and the Commonwealth.

- Established a functioning civil and legal service (admittedly based on the British model), and an unarmed police force, the Garda Síochána.

- Designed postage stamps and a currency for the Irish Free State, and successfully created an identity for the new nation.

Britain was watching what the Irish were doing very carefully. The Irish Free State was one of the first countries (since the Americans) who dared to challenge the British and go their own way. The British were aware of their commitments to Northern Ireland, and didn't want to see the Free State become an unsettled nation. How Ireland coped with independence would set precedents for other nations in the Empire. The British wanted everything to go smoothly.

While state building was a great adventure for the Irish, the reality was far more complex. Not only did they have an internal group, those in Sinn Fein, who disagreed with the very concept of the Free State, but they also had the perceived legacy of centuries of British rule to deal with. And of course the border issue and the very presence of Northern Ireland in what they considered their country.

Creating An Independent Irish Identity

At the beginning the leaders of the Free State engaged in many symbolic acts. For a start they painted all the postboxes green. Now that doesn't sound like a big deal, but it was hugely important. It announced to everyone who lived in the Free State that they no longer posted their letters into red British postboxes that would be processed by the Royal Mail. Instead they put their letters into green, Irish postboxes, and their letters would be dealt with by the postal service of the Free State.

In the same vein the Free State began issuing its first postage stamps, and introduced its own coinage and bank-notes. Strangely the coinage, although featuring depictions of Irish animals, was actually designed by an Englishman.

Landmark buildings in Dublin that had been destroyed during the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence, and the Civil War were rebuilt. By the late 1920s the Post Office, Custom House, and Four Courts had all been rebuilt and were open for business again.

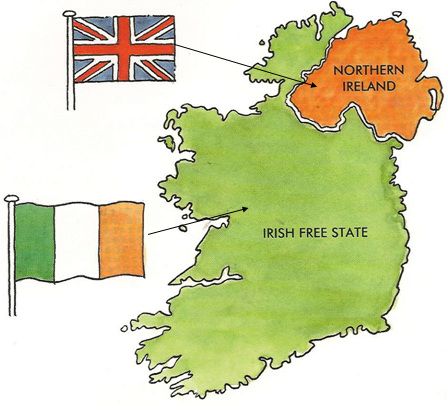

Unfinished Business: The Legacy of Partition

In the arguments over the Treaty that created the Irish Free State, Michael Collins acknowledged that it wasn't the 32-county Republic that people had fought for during the revolution. He argued that the Treaty, and the Free State it gave birth to, allowed Ireland "the freedom to achieve freedom." In other words, one of the great hopes for those who had supported the signing of the Treaty between Britain and Ireland was that partition wouldn't be permanent; that is, that some day, Ireland would be reunited. Article 12 of the Treaty had paved the way for a boundary commission to sit, and the Irish hoped that this would change the border in their favor.

The boundary commission finally came together in 1925. In the years between the signing of the Treaty and the boundary commission sitting, unionists had become increasingly hostile to the idea. Rather than take part in a body that they believed intended to shrink Northern Ireland, the unionists refused to send a representative.

In the event, the boundary commission suggested that the border be shortened by 51 miles, and some 31,319 people would end up as citizens of the Free State as a result. The news was leaked to the press, a political crisis followed, and in the end nothing was done. Rather than adjust the border, and risk upsetting everyone, the representatives of Northern Ireland, the Free State, and the British government agreed it would be simpler to leave things alone. They all signed an agreement that Article 12 should be forgotten, and the border should remain fixed as it had been drawn up in 1920.

So, for all of Michael Collins' "freedom to achieve freedom," the border wasn't up for redrawing. The partition remained a contentious issue, and politicians in the Free State were happy to use it as a propaganda tool. In real terms however, there was never any suggestion after 1925 that the border could be changed.