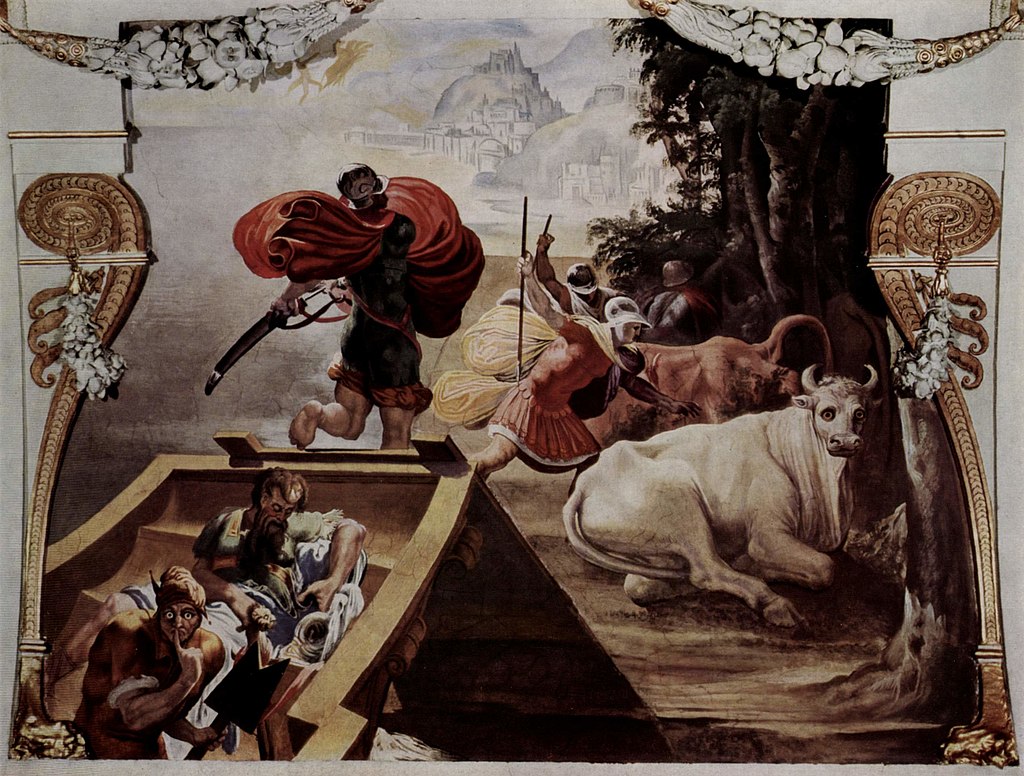

Oxen of the Sun

by Pellegrino Tibaldi (1554/56)

The Episode opens at 10 pm in the National Maternity Hospital, 29-31 Holles Street, presided over by Sir Andrew Horne. It begins with an invocation to the sun as a source of fertility, and the celebratory cry of a midwife who delivers a male child.

STYLE: The first style is an imitation of a literal translation of early Latin prose from the Roman historians Sallust (86-34 BCE) and Tacitus (c. 155-120 CE).

A passage considers the power of procreation as it is passed down from one generation to the next, and what can be said about a society based on its attitude toward procreation

(The style effects what subject matter the narrator focuses on. How Joyce is writing about something effects what he is writing about.)

STYLE: Literal translation of medieval Latin prose chronicles.

The passage considers the proud Irish medical tradition, particularly focusing on how pregnant women could be cared for whether they were wealthy or not.

It goes on to recount how Mina Purefoy was welcomed into the hospital, and many people gathered around her there in her suffering.

STYLE: Imitates the style of Anglo-Saxon rhythmic alliterative prose, most associated with Aelfric (955–1022 CE), the leading prose writer of the period.

The passage opens "Before born babe bliss had. Within womb won he worship" (14.7). The midwives are gathered around Purefoy's room, and Bloom enters the hospital from outside. He recalls a time when he did not acknowledge Purefoy in a townhouse meeting, and thinks that this is a kind of penance.

Bloom makes small talk with a nurse about a doctor O'Hare, who died young.

STYLE: Middle English prose, echoing in particular the morality play Everyman (c. 1485).

Bloom asks after Mina Purefoy, and Nurse Callan tells him that she is having a hard birth, that she has been having throes for three days. Bloom "felt with wonder women's woe in the travail that they have of motherhood" (14.13). He wonders that Nurse Callan is still a handmaid.

STYLE: Imitates the Travels of Sir John Mandeville (c. 1336–71), a medieval compilation of fantastic travel stories.

Bloom runs into Dr. Dixon, who once treated him for a bee sting. He decides to move into a room where a bunch of men are gathered having canned sardines and bread and drinks and enjoying themselves.

STYLE: Imitates the 15th- century prose of Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur (1485).

A nurse comes in and asks all of the men to be quiet. Lenehan in particular is making a ruckus. Gathered around the room are several doctors: Dixon, Lynch, Madden. Lenehan is there and so is Punch Costello, a medical student. Stephen is there and he is the drunkest of them all, though he still demands more beer. They are apparently waiting on Buck Mulligan (Malachi) who promised that he would come.

Dixon pours Bloom a beer, which he passes on to his neighbor when no one is looking.

Bloom thinks affectionately of Stephen.

Lenehan keeps pouring rounds as the doctors argue about the law that says if life is in danger during pregnancy, the child's life must take precedence over the mother's.

Madden recounts a case where a woman died and they all grieved.

Stephen begins speaking up about Church teachings, pointing out that if a child dies without being baptized it will go to Limbo, whereas if a mother dies she will go to Purgatory.

Stephen points out that lust is brief, and nature must have other ends in mind. Dixon, who is quite drunk, makes a joke of it.

Crotthers recalls a joke of Mulligan's, and they all laugh except for Bloom and Stephen. (Notice how the two are twinned in their isolation.) Stephen starts ranting against the Church and its teaching on pregnancy.

All the men are bachelors except for Bloom, and they ask him if he would risk Molly's life in order to have a child. He dodges the question. Stephen, very drunk, says, "he who stealeth from the poor lendeth to the Lord" (14.19).

Leopold feels glum and thinks back to his son Rudy. He then takes pity on Stephen for living so riotously and wasting his time with prostitutes

STYLE: Imitates Elizabethan Prose Chronicles.

Stephen begins pouring drinks and talking as if he is delivering communion. He shows the men some coins he obtained, which he claims are from a song that he wrote.

He begins pontificating, saying, "Time's ruins build eternity's mansions. What means this? Desire's wind blasts the thorntree but after it becomes from a bramblebush to be a rose upon the rood of time. Mark me now. In a woman's womb word is made flesh but in the spirit of the maker all flesh that passes becomes the word that shall not pass away" (14.21).

Stephen goes on at length about the church's convoluted teachings surrounding Mary's pregnancy with Jesus, and thinks that others can stick to their faith, but he will withstand.

Punch Costello begins singing a lewd song. Nurse Quigley comes in and tells all the men to be quiet and that they should be ashamed. They continue to be loud, except for Leopold who sits there quietly.

STYLE: A composite of late 16th, early 17th Latin prose styles: John Milton (1609–74), Richard Hooker (1554–1600), Sir Thomas Browne (1605–82), and Jeremy Taylor (1613–67).

Dixon and the others begin teasing Stephen about why he didn't take friar's vows. Lenehan makes a bawdy joke, and they all laugh in delight.

Stephen puns off the golden rule, saying, "Greater love than this no man hath that a man lay down his wife for a friend" (14.23).

Stephen pontificates at length on the passage from death to life.

Punch Costello busts into another bawdy song, and then a loud thunderclap is heard. Lynch teases that God is upset with Stephen's blasphemy, and Stephen is actually frightened and turns pale.

The men laugh, and Stephen tries to play it off by shouting that "old Nobodaddy was in his cups," and then burying himself in his drink (14.24). Bloom tries to soothe him by explaining to him the science of thunder.

STYLE: After John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (1675).

Stephen is not calmed by Bloom's explanation. He thinks, "he could not hear unless he had plugged up the tube Understanding" (14.25). Stephen remembers an encounter with a prostitute. He thinks that all men would listen to their lust compared to a faith that cannot be seen.

He again thinks that the thunderclap might have been a sign of the wrath of God.

STYLE: After the seventeenth-century diarists and friends John Evelyn (1620-1706) and Samuel Pepys (1633-1703).

The narration zooms out of the hospital and describes Dublin getting soaked by the evening shower.

On his way to the maternity hospital, Buck Mulligan bumps into Alec Bannon, who has just returned from Mullingar. He says that he met a "skittish heifer" there, referring to Milly Bloom (14.27). They head to the hospital together.

STYLE: After Daniel Defoe (1661–1731).

Lenehan and Costello are described as fairly worthless fellows, and the men begin to discuss the foot and mouth problem prevalent among Irish cows (the subject of Mr. Deasy's letter in Episode 3).

The talk of Irish cows gets them on the subject of papal bulls. They begin discussing all the various Henry's that oppressed Ireland over the years, beginning with Henry II who got papal permission to invade Ireland because he said it was a land of moral corruption and irreligion. They make of it one big joke, constantly punning on the word "bull."

STYLE: Imitates John Addison (1672-1719) and Richard Steele (1672-1719) who wrote famous periodical essays at the time.

Mulligan appears with Alec Bannon. He passed around some cards he has had made, which read: "Mr. Malachi Mulligan, Fertiliser and Incubator" (14.29).

Mulligan embellishes on his joke at length, describing how he will set up a clinic called Omphalos on Lambay Island. There he will fertilise any young woman who comes looking, and won't even take a penny for his pains. The men get a big kick out of it.

Mr. Dixon teases Mulligan about his girth in medical student talk. Mulligan pats his stomach and says, "There's a belly that never bore a bastard" (14.30). They all laugh uproariously.

STYLE: After the Irish-born novelist Laurence Stern (1713-1768).

Bannon tells Crotthers about Milly, and shows him a locket that he received from her. He says he wished he bought a condom to Mullingar, and says that he will buy some prophylactics while he is in Dublin.

The men begin to joke about contraception, talking in euphemisms. A bell from the hall cuts their conversation short.

STYLE: Imitates Irish-born man of letters Oliver Goldsmith (1728-74).

Nurse Callan comes in and tells Mr. Dixon that Mina Purefoy has given birth to a bouncing baby boy.

The men are very polite when she is there, but break into bawdy jokes about her attractiveness as soon as she leaves.

Mr. Dixon rebukes them.

STYLE: Imitates the Irish-born political philosopher Edmund Burke (1729-1797).

Bloom has been aware that, from time to time, the men have mocked him, but he has ignored it.

Bloom thinks disparagingly of "those who create themselves wits at the cost of feminine delicacy" (14.33).

He's very gladdened to hear of Mina Purefoy's birth.

STYLE: After Dublin-born dramatist and then successful member of Parliament, Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816).

Bloom remarks to his neighbor that the levity is out of place considering Purefoy's pain. The neighbor remarks that it's her husband's fault, or at least that of some other "man in the gap" (14.34).

Crotthers leads a toast to Mr. Purefoy for still being able to get another baby out of his wife.

Bloom is astonished that these men are actually medical professionals.

STYLE: After savage 18th-century satirist Junius.

A long passage interrogates all the in and outs of Bloom's hypocritical judgment of the others in the room.

STYLE: Imitates the skeptical anticlerical philosopher historian Edward Gibbons (1737-1794).

A delegate comes and formally announces the birth to the gathered group. Bloom tries to tell them all to restrain themselves, but is ignored.

The men burst into a discussion of all sorts of medical matters and superstitions related to birth and birth defects. Amongst them are Caesarean sections, miscarriages, infanticide, rape, and Siamese twins.

Stephen acts as room deacon and says that they cannot curse what God has made possible.

STYLE: After Horace Walpole's gothic novel The Castle of Otranto (1764).

Mulligan tells a mock-ghost story involving Haines, in which Mulligan confesses to being the real murderer of Sam Childs. Throughout, he makes use of Stephen's sayings from the day, using them as if they are his own. In particular, he parodies Stephen's "Hamlet" theory.

STYLE: Imitates English essayist Charles Lamb (1775-1834), known for his pathos and his nostalgia.

Bloom remembers himself as a young boy, and then realizes that he is now in a paternal role and the men around him are like his sons.

He thinks, "There is none now to be for Leopold what Leopold was for Rudolph" (14.38).

STYLE: After English Romantic Thomas de Quincey (1785-1859).

Bloom becomes gloomy as the prose becomes more hallucinatory. He thinks of the ephemeral nature of life, and then has a vision of Martha Clifford.

STYLE: After the essayist Walter Savage (1775-1864).

Lenehan and Lynch tease Stephen about his youth, and his (as yet unfulfilled) ambition. They cross the line when Lenehan kids Stephen about the death of his mother.

The men begin to discuss the Gold Cup race. Lenehan recounts the finish, where Throwaway came from behind and beat Sceptre.

Lynch reveals to Lenehan that he and his girlfriend Kitty were messing around in the bushes and were nearly caught by Father Conmee (in Episode 10, "The Wandering Rocks").

Mulligan cracks a joke about Stephen, but Stephen does not pick up on it and begins discussing the philosopher Theosophos. (Again-if you're interested in following up on all of these allusions check out Ulysses Annotated.)

STYLE: Imitates English essayist and historian Thomas Babington Macauley (1800-1859).

Stephen has been eying a bottle of Bass for a long time, and eventually goes for it.

A debate ensues, and all of the men around the table are described at length.

STYLE: Imitates English naturalist and anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895).

The narrator notes that Stephen's "perverted transcendentalism" won't go very far in a discussion of science (14.43).

Bloom begins the discussion by wondering how the sex of the child is determined.

He then turns the subject to infant mortality, remarking, "we are all born in the same way but we all die in different ways" (14.43).

Mulligan thinks infant mortality is due to bad sanitary conditions, and then suggests that better lifestyle would reduce infant mortality. Crotthers suggests it may be abnormal trauma of women workers, but is probably mainly neglect. Lynch suggests it has something to do with an as yet undiscovered law of numeration. Stephen throws out a far-fetched opinion, and the narrator recalls a recent debate between Bloom and Horne (master of the National Maternity Hospital) on the subject.

STYLE: After Charles Dickens's David Copperfield (1849-1850).

Mina Purefoy holds her baby before her and admires it joyfully. She thinks of her husband and all their other children, and decides to name it Mortimer Edward after a third cousin.

STYLE: Imitates English convert to Roman Catholicism, Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890).

A passage describing how sins become shrouded in a man's past but continue to reproach him in the present.

STYLE: Imitates English aesthetician and essayist Walter Pater (1839-1894).

Bloom observes Stephen closely and thinks that he is putting on a false calm. He remembers him as a gloomy young child, distanced from his mother.

STYLE: After English art critic and reformer John Ruskin (1819-1900).

The assembly of men who, for the moment, sit calmly is compared to the gathering around Jesus' crib in Bethlehem.

STYLE: After Scottish man of letters Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881).

Stephen cries that they should all go to Burke's pub. The men make a ruckus as they gather their things and head out of the hospital. Dixon follows behind, rebuking them lightly, but proceeds along with them.

Bloom hangs back and has a word with Nurse Callan. He asks her to pass on a kind word to Mina Purefoy, and asks if Callan will be expecting a child anytime soon.

As the men hustle out into the street, their praises of Mr. Purefoy's virility and Mrs. Purefoy's fertility and their calls to drink are all exaggerated in Carlyle's style.

STYLE: From here on out (14.50), the style disintegrates into dialect and slang. In the words of Joyce, it becomes "a frightful jumble of pidgin English, [black] English, Cockney, Irish, Bowery slang and broken doggerel."

The men talk over each other on a variety of subjects as they proceed to the pub. Indeed, the next few pages are all conveyed in nonstop overlapping dialogue.

Stephen is the one pressing the drinking. He buys the first round and then the second, taking absinthe for himself both times.

Alec Bannon is still bragging about Milly, but eventually realizes the relation to Bloom and slinks off.

Some other men gossip about the mysterious man in the mackintosh at Dignam's funeral.

The fire brigade passes on its way to a fire. (Notice that by now the speech has become so broken that it's extremely hard for the reader to understand.)

Someone pukes outside, and the men begin to make their way out as it's nearing closing time. Stephen convinces Lynch to proceed to Nighttown with him (the red light district), and Bloom follows behind.

As the episode closes, the language becomes like that of an advertising sales pitch: "You'll need to rise precious early, you sinner there, if you want to diddle the Almighty God. Pflaaaap! Not half. He's got a coughmixture with a punch in it for you, my friend, in his backpocket. Just you try it on" (14.59).

First of all, do not fret. "Nausicaa" is one of the easier episodes in Ulysses, and then right on its heels comes "Oxen of the Sun," quite possibly the hardest. Joyce has brought all of his stylistic powers of imitation to bear in the chapter, and the result is that the prose can be extremely dense and hard to parse. But style is the thing that makes "Oxen of the Sun" one of the most remarkable chapters in the novel.

"Oxen of the Sun" is written in over twenty different styles, each one parodied chronologically. The episode begins with literal translations of early Latinate prose, moves into Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse, then the Renaissance works of various authors, then up into 18th and 19th century novels. In the last few pages, the style dissolves into a mix of Irish dialects and Dublin slang. In short, Joyce provides a stylistic guide to the history of Western literature (with a strong Irish emphasis) in just over 40 pages.

Furthermore, Joyce attempts to demonstrate the ways in which style is utterly inseparable form content: how you write about something determines what you write about. If you read the episode over a couple of times, you'll begin to notice how a given writing style moves over the scene like a magnet and picks up the pieces that it is most prone to focus on.

For example, the early Latinate prose, always trying to get a taste of history, speaks in generalities of the powers of procreation and the proud Irish medical tradition, while the Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse is used almost as baby-talk to imagine the state of bliss before an infant is delivered: "Before born babe bliss had. Within womb won he worship" (14.7). The style of the morality play Everyman is used to capture the seriousness with which Nurse Callan describes the difficulty of Mina Purefoy's birth. As Bloom judges the other men for being too rowdy in the hospital, the hypocritical nature of his thoughts is rendered in the savage 18th-century satirical style of Junius. Finally, the drunken cross-talk of the men in Burke's pub is rendered in Dublin slang and colloquialisms. Joyce's didactic point: form is content; content is form.

Joyce once wrote in a letter to a friend (probably half-seriously) that in this episode, "Bloom is the spermatozoon, hospital the womb, the nurses the ovum, Stephen the embryo." What he was getting at is that the stylistic effect in the chapter is a metaphor for the process of gestation that takes place during pregnancy. The episode is set in a maternity ward while the men wait to hear news of Mina Purefoy's birth. When Mulligan comes in, they actually joke about how fat he is and suspect that he too is pregnant with child. Yet the chapter suggests that the male creative process is different than that of the female. As the artist's prose style moves through the evolution of prose style in literary history, it seems to be suggesting that men give birth to books, not children. All Stephen's moodiness surrounding his ambition to write a great masterpiece might be something like a mother's labor pains. And in Ulysses, Stephen, like Mina Purefoy, is having a hard time giving birth.

"Oxen of the Sun" corresponds to Book 12 of The Odyssey, where Odysseus and his men land on the island of Helios, the sun-god. Odysseus has been warned not to harm the cattle on the island, and asks his crew to swear the same. When he falls asleep one of the crew members, Eurylochus, convinces the men to forget their oath and to slaughter the cattle. Odysseus wakes up in despair, but realizes that there is nothing to be done. After seven days on the island, they depart, but Helios appeals to Zeus, who promptly destroys their ship with a lightning bolt. Odysseus lashes the mast to keel of his shattered ship and endures the voyage alone.

There are a number of small correlations throughout the Ulysses episode. For one, Bloom has just woken up from his nap in "Nausicaa," like Odysseus on the island. For another, the men are mocking women and the process of giving birth despite Bloom's calls for moderation, just as Odysseus's crew slaughtered the cattle despite Odysseus's warnings. Zeus's thunderbolt here comes in the form of a thunderclap that makes Stephen fear that the gods have heard his blasphemy. At the end of the episode, the prose seems to be extremely "stormy" and hard to get a handle on, and Bloom is very much alone.

The key correlation, however, is between the oxen and fertility. All the men discuss pregnancy at length, but they often make a joke of it, and never think to empathize with the pain that the women are going through. Bloom, by contrast, "felt with wonder women's woe in the travail that they have of motherhood" (14.13). Bloom alone amongst the men recognizes the sanctity of womanhood just as Odysseus is the only one to recognize the sacredness of the cows.

On a simpler thematic level, Bloom and Stephen are drawn more closely together in "Oxen of the Sun" than at any previous point in the book. Bloom observes Stephen as they sit there in the room. He has a number of fatherly feelings for Stephen: he takes pity on him, thinks he is wasting his time drinking and spending time with prostitutes, and suspects that the calm demeanor Stephen puts on is blatantly false. When Stephen is scared by the thunderclap, it is Bloom who tries to calm him.

As Bloom begins to act fatherly toward Stephen, we also see how the two are twinned in their loneliness. Bloom is roundly ignored in the room, and when he attempts to launch into a scientific discussion of infant mortality, the men quickly begin talking over him. In "Aeolus," Stephen appeared in his element and was surrounded by admiring newspapermen. Here, by contrast, we see Stephen in a more typical state. He pontificates about religious matters at length and is kidded by the other young men for being overly ambitious and not achieving anything. As Stephen and Bloom become more outcast by the group, they drift closer and closer together.