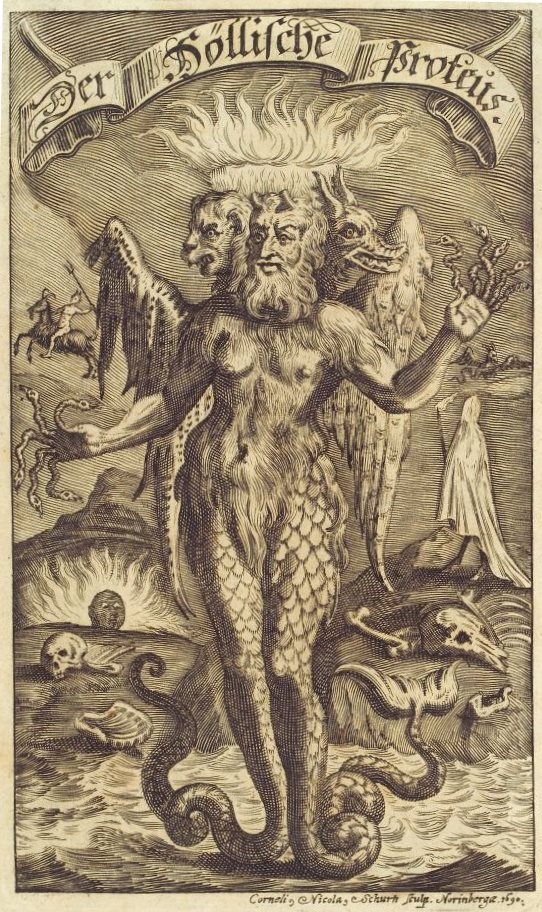

Proteus

by Cornelius Nicholas Schurtz (1690)

It's about 11am, and Stephen has come to Dublin from Dalkey by way of public transportation. As you might recall, he has a set meeting with Mulligan at 12:30, and in the meantime he has wandered down to Sandymount Strand (the beach at the east-most side of Dublin) to stroll along the beach and think.

Stephen thinks about different theories of vision, Aristotle's in particular. He also considers Bishop Berkeley's theory that there is no such thing as matter, and how Aristotle refuted it (same way Samuel Johnson did, by hitting something made up of matter. In other words, he appealed to common sense.).

Stephen closes his eyes and taps his way along the beach with his walking stick.

Stephen wanders along the beach and thinks about his movement along the beach in relation to the German Gotthold Lessing's theory of the difference between visual arts and poetry. (According to this theory, action is progressive [nacheinander] versus stationary [nebeneinander]). He puns on an Irish tune as he passes by the Church of Mary, and then thinks of his steps in relation to poetic meter.

He opens his eyes.

Stephen imagines for a moment that he is trapped in eternal darkness, then looks up to Leahy's terrace and observes a couple coming down onto the beach. The woman is a carrying a midwife's bag and he thinks that perhaps there is a misbirth in it with a trailing navelcord. He imagines the umbilical cord as something that runs back through history and time and binds all men together, and the thinks of it like a telephone line and imagines that he can call Eden by dialing "nought, nought, one" (3.6).

Stephen thinks of Adam and Eve, and how his existence was also ordained by God and is evidence of God's will. He (as before) remains pre-occupied with how the Father and Son can be of one substance, and then thinks of the heretic Arius who wanted to return to the faith, but died in a public toilet and was mocked by his rivals.

Stephen notes that he was "made not begotten" meaning that his soul is not of one essence with his father's as is the case with God and Jesus (3.8). We notice that even though Stephen speaks like a heretic he's obsessed with religious ideas and imagery.

The waves roll in and Stephen imagines them as the manes of the horses of the Irish God of the Sea (Mananaan).

Stephen remembers Deasy's letter for the press, and he remembers that he is supposed to meet Buck Mulligan and Haines at The Ship at 12:30.

He slows down when he passes by his Aunt Sara's house. He imagines his father asking Sara about him and making fun of how he has not flown as high as he would have liked (Note the allusion to Icarus and Daedalus).

Stephen is ashamed of his family.

Stephen then imagines the scene if he were to enter Sara's house. He would be let in by his young cousin Walter and then would be greeted by his uncle Richie from bed. Richie would abuse Walter and demand that he prepare a malt and a seat for Stephen (this is all imagined, remember).

At the mental cry of the Italian 'All'erta!' Stephen snaps out of his dream (3.30). He thinks of the opera, and then considers how he is from a house of decay just as the Ferrando's Italian opera depicts the house of Cain and Abel as one of decay.

He thinks of the heretic Abbas and the famous misanthropy of Jonathan Swift. He imagines Swift climbing up a pole to get away from the people and all the false priests gathering around and calling for him to descend.

Stephen thinks of Dan Occam who coined Occam's razor (philosophical idea that a logical argument should be as concise as possible), and then he thinks of priests and his early saintly ambitions. He imagines his early longing, and his literary ambition. He jokingly and self-deprecatingly thinks of how he imagined the critical acclaim around his books.

Stephen feels the water run up through his feet, and smells the sewage of Dublin which has been dumped into the Liffey and run off into the ocean.

He notices that he has passed his aunt Sara's house, and realizes that he will not go there (Notice how trapped in his head Stephen is. He barely maintains touch with the physical world at all.).

Stephen turns northeast toward Pigeonhouse.

He thinks of the Virgin Mary's claim that she was impregnated by a pigeon (recorded in La Vie de Jésus by M. Leo Taxil).

He recalls spending time with Kevin Egan in Paris, another Irishman in exile. He recalls some of their conversations, and how they dressed, and how poor they were. He recalls being a medical student, and how he used to carry punched tickets everywhere so that if there were a murder, he would have an alibi.

Stephen remembers a time in Paris when he went to the post office with his mother's money order, but arrived too late. He again recalls how huge his ambitions were when he went to Paris, how he thought that he would be like a great Irish missionary.

Then Stephen remembers the brief telegram from his father that ended his time in Paris, "Mother dying come home father" (3.51).

He again recalls Buck Mulligan's claim that he killed his mother, and a few lines from the Irish songwriter Percy French's, "Matthew Hanigan's Aunt."

Stephen recalls the atmosphere of Paris: its sights and sounds.

He recalls his time with the Irish nationalist Kevin Egan. Egan would tell him all sorts of stories over cigarettes about his involvement with the Irish nationalists, and the peculiar habits of the French. Because Egan was involved in violence as a nationalist, when he would roll his cigarettes it made Stephen think of gunpowder.

In Stephen's memory, Egan goes on about being a spurned lover, and reflects on his position as an Irish exile in Paris. He asks Stephen to give his regards to the people back home.

Stephen feels the wet sand on his boots, and realizes that he has gone quite far. He thinks that he will turn back.

He thinks of Haines and Buck Mulligan waiting for him back in the tower, and vows again not to go back. He imagines a way back, and then sits for a moment on a stool of rock, putting his walking stick in a crack.

Stephen sees the bloated carcass of a dog, and thinks, "These heavy sands are language tide and wind have silted here" (3.62). He free-associates a wee-bit.

A live dog comes running toward him, and for a moment he is frightened. Then it turns and runs back to two people walking along the beach. Stephen thinks they were probably messing around (Note how the physical world is becoming more prominent in the episode. We are no longer just stuck in Stephen's thoughts.).

Stephen thinks of when the Vikings came to the beach, and the ways in which his life is continuous with theirs.

The dog comes running back, and then Stephen thinks of various pretenders throughout history. He wonders if he is a pretender. He thinks of his cowardice, and recalls a man that was drowned recently. He wonders if he would swim out to sea and save him. It makes him think of how he could not save his mother, and he is overcome with a sense of loss.

Stephen observes the people and their dog on the beach. The dog sniffs the dead dog's carcass, and the people yell at it to get away. The dog wanders off and begins digging, and it makes Stephen think of the riddle that he told in class that day.

Stephen recalls a dream he had the night before about a man with a melon leading him down a red carpet.

He observes the man and the woman, and the woman makes him think of a sexual encounter that he had in Fumbally's lane. (In other words, we learn that Stephen continued to see prostitutes, as he did in Portrait.)

Stephen thinks of some lines from "The Rogue's Delight in Praise of his Strolling Mort," by Richard Head.

He thinks of Aquinas and how prickly his philosophy is, and imagines that his own language is no worse than Aquinas's.

The couple passes, and they look at Stephen's hat. Stephen begins improvising on Percy Bysshe Shelley's Hellas and then gets carried away with wordplay. He starts jotting down a poem on a scrap from Deasey's letter. (Note: this is the first time we see him create anything.)

Stephen wonders who will ever read his poem and feels very lonely.

Stephen tries to imagine a woman that would be the subject of his poem. He thinks of a girl that he glanced at in a bookstore, and feels a poignant loneliness. He realizes that he does not know "that word known to all men," i.e., love (3.80).

Stephen leans back on the rock and tries not to brood. He worries that his walking cane will float away as the tide comes up. Then Stephen pees.

Stephen thinks of the corpse of the recently drowned man rising to the surface of the water and the people pulling it in.

He thinks of how mild a death at sea is for a man, and takes his walking stick. He muses on poetry, and then thinks of how bad his teeth are. He wonders if he has enough money to go to a dentist.

Stephen tries to remember if he picked up his handkerchief after Mulligan threw it at him. When he realizes he didn't, he picks his nose.

He thinks that he doesn't care who sees, but then gets worried that there is someone behind him. He sees a ship coming into the bay.

The first two sections of Ulysses are by no means easy, but this one steps it up a notch. First of all, Don't Panic! Later parts of the book again become easier, and you can't be expected to get too much out of "Proteus" on a first or even a second read.

First, let's reflect on how far we've come. What makes the first two sections of Ulysses difficult is the sudden un-announced turn, a few pages in, to Stephen's stream-of-consciousness. There isn't any introductory phrase announcing this as interior monologue, e.g. "And then Stephen thought, in a free-wheeling manner based largely upon puns..." As a result, it is hard to distinguish the dialogue and the action of the scene from Stephen's own interior thoughts.

But this isn't just difficulty for the sake of difficulty. Think of it this way. Your girlfriend or boyfriend just broke up with you and you have coffee. Afterward you are trying to determine whether or not they seemed happy. You're trying to be objective about it, but you can't help emphasizing certain things about the scene as a result of your subjective prejudice. Since your ex is supposed to be sorry that they left you and secretly sad, you project your desire to have them seem sad onto the scene and imagine, for instance, a little bit of sadness in their voice that may or may not be there. You have trouble distinguishing the external world – what's actually out there – from the internal world – what's just going on in your head.

This may be a silly example, but knowing how self-absorbed Stephen is we can realize that he's constantly faced with the mad-rush of his own thoughts and external reality going on at the same time. In extreme cases, the two can become indistinguishable.

Now, in "Proteus," the trouble isn't determining the external from the internal or deciding who is talking because it's all Stephen. The difficulty now is just following his train of thought, which can often turn on references that the average reader doesn't know much about. Let's look at just the first paragraph as an example:

The opening: "Ineluctable modality of the visible" alludes to the Aristotelian idea that when we look at something, the thing itself is not part of what we see. We see just a pure form, but the substance – the thing out in the world – is entirely separate. According to Aristotle, this is different than sound, for example, because in sound some of the substance gets mixed up with the pure form in the process of hearing. Vision is unique, then, because what we perceive (the form) and what exists (the substance) are distinct.

When Stephen then thinks of "Signatures of all things" he is thinking of the philosophy of the German mystic Jakob Boehme who maintained that a thing can only be encountered through its opposite. For Stephen, this is tied to the first idea because, in the case of vision, form is opposed to substance. Thus, what Stephen is actually perceiving as he looks around Sandymount Strand is just a signature and not at all the thing itself. Again, the idea is that the world is different, perhaps only distantly related, to how we perceive it.

Stephen then goes on to think about Aristotle's ideas about transparence (the diaphane) and how transparency is something that is common in nature, and is not just a property of specific objects. Transparency is not just limited to things like water and glass; it is everywhere. But, Aristotle being a smart guy and all, he realized that we need a way to keep everything from being see-through. Thus, he suggested that transparency is limited by the color that exists in actual objects.

Stephen then thinks of the philosopher Bishop Berkeley and his theory that there is no such thing as matter, that nothing exists outside of one's own mind (solipsism). Stephen remembers how Aristotle refuted this by just hitting a material object (just like Samuel Johnson did). The basic idea being: "No such thing as matter! Ha! Look, I just kicked a stone and now my toes hurt! I refute you! There is such a thing as matter!"

Stephen then thinks about what is known of Aristotle's biography: that he was a blind millionaire. He goes on to quote a line from Dante in Italian saying that Aristotle was "the master of all those that know," and closes by thinking about the silly distinction that Samuel Johnson made between a gate and a door in his first English Dictionary. This again plays into Stephen's ideas about the distance between what we think of (gates and doors) and what actually exists out in the world (things that we classify neatly as gates and doors, but that may be gates or doors or something else entirely).

Stephen closes his eyes to see if he will still register evidence of the external world.

And that's the first paragraph. We take a deep breath and think of how to sum up the gist of all this in a single sentence. We might say, for example, that Stephen considers ancient ideas about solipsism and the existence of an external world, and wonders how the thoughts in his head relate to the world around him.

Point being: As you read, don't get panicked about all the references or the fact that you sometimes lose track of what's going on (very little happens in this chapter). Recognize that you can delight in the beauty and erudition of Joyce's prose without understanding every last little detail. Think of Stephen as the smartest professor you can imagine whose mind goes faster than the average mind and now he's wandering up and down the beach spitting thoughts in a disordered fashion at 100 miles per hour.

Here are a few of the big ideas you might be on the lookout for as you move through the chapter.

First, what is Proteus? In Greek mythology, Proteus is the shape-shifting son of Poseidon who has the power of prophecy. Menelaus, attempting to return home from the Trojan War, knew that one of the gods had a grudge against him and he wanted to find out which one. To do so, he had to pin down Proteus, who was a shape-shifter and took the form of beasts, water, and fire. But Menelaus held tight and Proteus gave him news of the difficult journey that Odysseus was trying to make home, and of the deaths of Ajax and Agamemnon. Menelaus recounts all of this to Telemachus in Book 4 of The Odyssey.

Here, Stephen's thoughts have a decidedly protean nature, constantly turning from one to the next. He tries to maintain a handle on them just as Menelaus tried to maintain a handle on Proteus, but he can't glance at anything along the beach without thinking of a dozen new references. Stephen's mind is so saturated with knowledge that he sees the whole world as being intertwined with language. Perhaps the key line of the chapter is: "These heavy sands are language tide and wind have silted here" (3.62).

We should note that, though Stephen's thoughts are hyper-abstract in the first part of this chapter, they gradually become more and more focused on the world around him – particularly when he sees the couple with the dog. Though still spinning out beautiful prose, his mind cools down toward the end of the chapter. It is at this point, during the cooling off period, that Stephen gets out of the abstract and becomes focused on the external world, that he actually writes his poem on the rock. After this, Stephen becomes even more a person "in the world" when we find him doing the very ordinary bodily business of going to pee and then picking his nose to make sure no one is watching.

Stephen's thoughts also wander back to his past, and we learn a few more details about his time in Paris with the exiled Irish nationalist Kevin Egan (whom Joyce lists as the Menelaus figure for this episode), and why he was called back to Ireland. This is where we get a real glimpse of Stephen's growing maturity. In Portrait, Stephen takes off for Paris with dreams of the great art that he will produce, and he seems to resent his family and his hometown. Yet, by interacting with Egan, Stephen found that the problems of Ireland followed him straight to Paris. Since Stephen had to return to Ireland as something of a failure, he was greatly humbled. Stephen now manages to joke about his early vanity and ambition. Though this makes him a much more tolerable character, it doesn't hide the fact that his mind is still aflame with something akin to literary genius.

We also get a real sense of how alone Stephen is in this chapter. He opens by thinking about solipsism, and is preoccupied with ideas about decay and images of the man that recently fell off a rock in the bay and was drowned. His thoughts occasionally slip back to his mother and the remorse he feels for not praying over her. Furthermore, when Stephen writes his poem, he realizes that he has no one to give it to and that there is no one to read it. Stephen's artistic ambition and his egotism have cut him off from people, and it does not help that he feels estranged from his father. In Paris, we see that the older Kevin Egan took Stephen under his wing (paralleling the Telemachus-Menelaus relationship in The Odyssey), but Egan was only a temporary surrogate father figure.

The next chapter turns to the actual Ulysses figure of Joyce's novel, Leopold Bloom, who will also become a sort of father figure for Stephen. Perhaps a good last-thought for Proteus is to muse, not only on Stephen's longing for a father, but on the ways that his brilliant intellectualism has not exactly done him a lot of good – it has isolated him from humanity.

What is that word known to all men? Answer: Love.