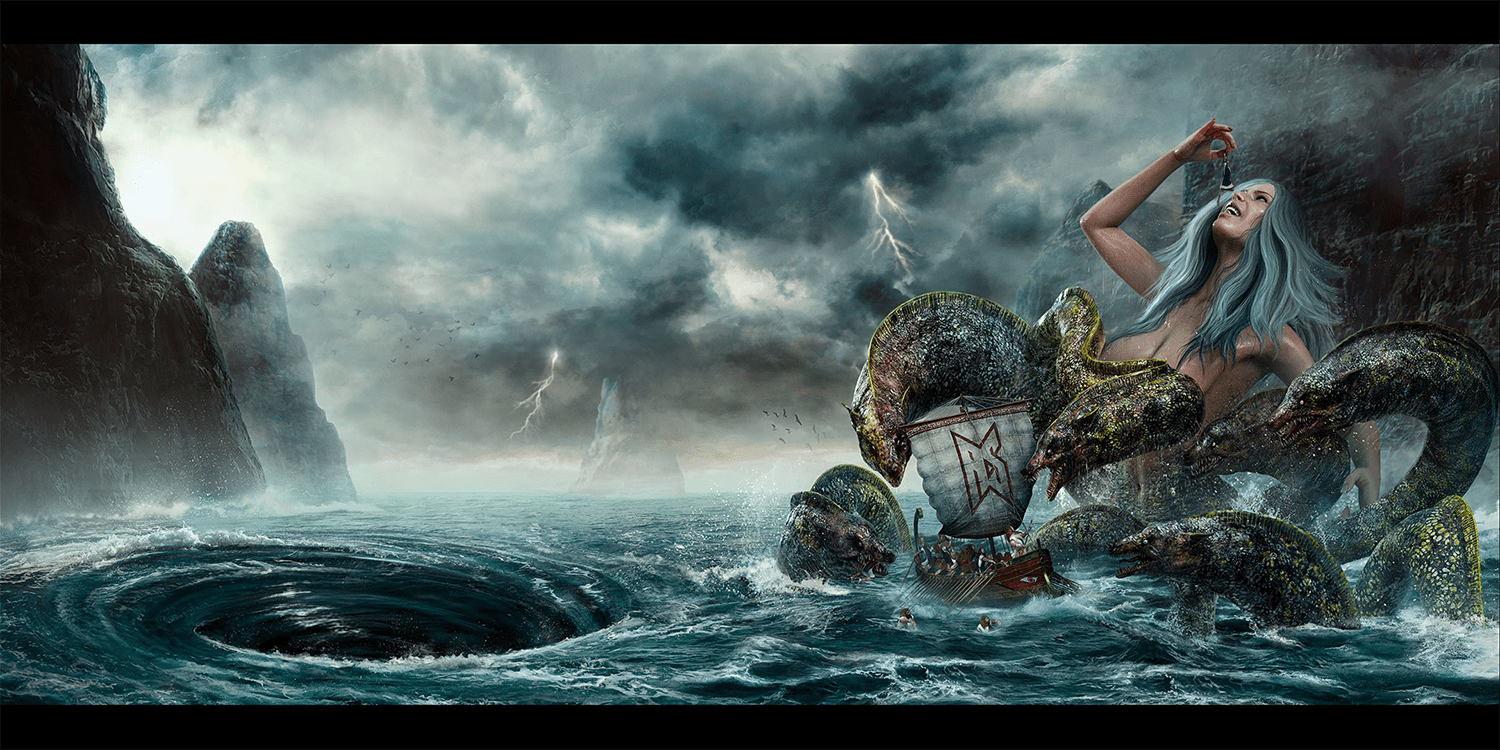

Scylla and Charybdis

a path between between two opposing dangers.

The librarian, Mr. Lyster, admires the work of Goethe, but then is called aside by an attendant. He slips out of the room and leaves Stephen Dedalus, John Eglinton, and George William Russell.

Eglinton, in light mockery, asks Stephen if he has found six young people to whom he can dictate his work. He suggests that Stephen will try to re-write Paradise Lost, but from Satan's point of view.

Russell pipes in and suggests that Stephen would need seven disciples if he were to write something like Hamlet because seven is a mystical number. He laughs.

Stephen juxtaposes some lines of Paradise Lost with some from the Inferno. He thinks upon what his friend Cranly once said, that twelve men with resolution could free Ireland. He puts Cranly's lines in the context of a play by W.B. Yeats.

Stephen remembers that Mulligan has his telegram, and silently coaxes himself to persist in his argument with Eglinton and Russell.

Eglinton argues that no young Irishman has created a figure to compare with Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Russell is irritated with Stephen's attempts to explain Hamlet from a biographical point of view, and suggests that these questions are purely academic and otherwise irrelevant. We enter this discussion in media res.

Russell thinks that, "Art has to reveal to us ideas, formless spiritual essences. The supreme question about a work of art is out of how deep a life does it spring" (9.18). He thinks that such conversation is only fit for schoolboys.

Stephen retorts that schoolmen were schoolboys first, and that Aristotle was Plato's student.

Eglinton hopes that Aristotle is still regarded as nothing more than Plato's student.

Stephen jokingly thinks to himself about Catholic beliefs on the trinity.

The library director, Mr. Richard Best, enters.

Stephen says that Aristotle would find Hamlet's musing as shallow as Plato's.

Eglinton says it irritates him to no end to hear Aristotle be compared to Plato.

Stephen points out that Plato would have banished poets from his commonwealth. He continues to joke inwardly about the idea of formless essences of things.

Mr. Best informs Eglinton that Haines, the Englishman, is very interested in Hyde's Lovesongs of Connacht.

Eglinton thinks that all Haines's smoking is going to his head. Stephen thinks disparaging thoughts about Haines.

Russell makes a stump speech about the power of lovesongs. He thinks that the real power in poetry comes from the hearts of simple peasants. Russell references Mallarmé.

Mr. Best, picking up on the reference, remembers some lines of Mallarmé's about Hamlet. Mallarmé had described Hamlet as distracted, which Stephen translates loosely as "the absentminded beggar" (9.44).

Eglinton laughs.

Stephen recalls a critic who referred to Hamlet as "a deathsman of the soul" (9.48). He again remembers his friend Cranly.

Eglinton says dismissively to Mr. Best that Stephen wants to think of Hamlet as a ghost story.

Stephen asks if a ghost is any more than "one who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners" (9.53).

He invokes a scene in which Shakespeare goes to his own play and plays the part of Hamlet's father – the ghost. He suggests that Shakespeare's son, Hamnet, who died prematurely, actually corresponds to the part of Hamlet. Quoting some of Shakespeare's early plays, Stephen then suggests that Ann Hathaway corresponds to the guilty queen who betrayed king Hamlet. (The key point is that Shakespeare can draw on his life for his art.)

Russell reiterates his point that prying into the life of a man, his drinking and his debts, is irrelevant. He says, "We have King Lear: and it is immortal" (9.64).

Mr. Best makes a sign that he agrees with Russell. Stephen free-associates in his mind, and remembers that he owes Russell some money. He wonders if he is a wholly different person than he used to be since the molecules in one's body all change over time.

Eglinton points out that Stephen is flying in the face of literary tradition. He suggests that Hathaway was always a martyr for literature, that she died before she was born.

Stephen retorts with the truism that she died when she was 67. He thinks of Ann's death and then of his mother's, and how he wept for her by himself.

Eglinton suggests that Shakespeare's marriage to Hathaway was just a mistake.

Stephen snaps back, "Bosh! A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery" (9.90). (We again get a glimpse of what an arrogant and stubborn young man Stephen Dedalus is.)

Lyster re-enters.

Eglinton argues that Hathaway was a shrew and could hardly have been a portal of discovery. He wonders what Socrates learned from his ill-tempered wife, Xanthippe.

Stephen suggests that Socrates learned dialectic from her. He compares the members of Sinn Fein to those who condemned Socrates to death.

Mr. Best points out that they are forgetting Hathaway.

Stephen, again appealing to material from Shakespeare's plays, argues that Hathaway was the older and wiser of the two and that she seduced Shakespeare.

Mr. Best murmurs some lines from As You Like It. Stephen observes that he seems very self-satisfied.

Russell announces that he has to leave, and Eglinton asks if he will be at the poet George Moore's reading this evening. He announces to the group that Russell is putting together a young group of Irish poets.

Stephen, feeling rebuffed on two accounts, distracts himself by looking down at his cane and thinking about Aristotle. He listens on as they discuss Moore and how Mulligan and Haines will be going tonight. (He's embarrassed at not being invited to the reading.)

Stephen thanks Russell for passing on Deasy's letter and making an effort to print it. Russell announces that they are also printing a letter of Synge's.

Lyster compliments Stephen on his views, and asks him whether or not Hathaway cheated on Shakespeare.

Stephen wonders whether the librarian is actually curious or if he is just being kind, but he responds, "Where there is a reconciliation, there must first have been a sundering" (9.129).

Stephen thinks about the similarities between the careers of George Fox, founder of the Quakers, and Shakespeare. Russell leaves. Stephen goes on pondering things that might have happened: what Caesar would have done with life if he listened to the soothsayer, what name Achilles had when he was amidst women.

He thinks of some lines of Goethe's.

Eglinton re-starts their conversation on Shakespeare, pointing out that he is the most enigmatic of great men because so little is known of his life.

Mr. Best argues that Hamlet is the most personal and revealing of plays.

Eglinton smiles condescendingly. He tells Stephen that Mulligan had warned him that he would be in for some paradoxes, but that Stephen will have to work harder if he is going to shake Eglinton's belief that Shakespeare corresponds to Hamlet.

Stephen very eloquently argues that Shakespeare had such a huge imagination that he could correspond to a number of different characters. Mr. Best agrees with him.

Eglinton is not pleased, and says that if that were how one measured genius than "genius would be a drug in the market" (9.152).

Stephen goes on by pointing out that the plays of Shakespeare's middle period are tragedies. Yet his later plays are lighter, full of female characters, because it was at this time that Shakespeare had a granddaughter and was somewhat reconciled in his feelings toward Hathaway.

Eglinton questions Shakespeare's role in writing one of the plays Stephen cites, and quotes a critic who says that Shakespeare could always stick to high human affections.

Stephen thinks that Eglinton is distorting Bacon, and considers the paper-thin theory that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays.

Stephen cites a critic suggesting that the birth of Shakespeare's granddaughter coincides with the beginning of the period of his late plays. Eglinton is skeptical.

Lyster hopes Stephen will publish his theories on Shakespeare. He notes several other Irish commentators, including George Bernard Shaw, who are publishing on Shakespeare. He then brings up the rumor that William Herbert (W.H. from The Sonnets) was the one who betrayed Shakespeare.

Stephen goes on to suggest that this betrayal of Shakespeare forced him into a darker understanding of himself. He points out that Hamlet's father knows the means of his own death, and he claims that he could only know this if it was told him by his Creator, namely Shakespeare. He thus argues that Hamlet's father is a part of Shakespeare himself, a way that he hid himself from himself. Yet he goes on to argue that although Shakespeare did not undergo self-recognition, he has been immortalized as a personality in the ghost of king Hamlet, "a voice heard only in the heart of him who is the substance of his shadow, the son consubstantial with the father" (9.172).

Mulligan, standing in the doorway, mockingly applauds Stephen's speech. Stephen thinks of him as betrayer and an enemy. He playfully free-associates about the theological idea that the father and son are inseparable.

Lyster asks if Mulligan has a theory of Shakespeare, and Mulligan jokingly pretends that he doesn't know who that is. He asks if it is "the chap that writes like Synge" (9.188).

Mr. Best announces that Buck Mulligan just missed Haines, who passed through earlier.

Eglinton brings up another theory that Hamlet is an Irishman.

Mr. Best says that his favorite piece of criticism is Oscar Wilde's piece on the identity of W.H., to whom Shakespeare's Sonnets are dedicated. He admires the light touch of Wilde. Stephen thinks of Wilde's wit.

Lyster wonders if Wilde is just writing paradox. He says, "the mocker is never taken seriously when he is most serious" (9.204).

Mulligan presents Stephen's bizarre telegram, which he sent instead of showing up to the Ship at 12:30 to drink with Mulligan and Haines. The telegram reads, "The sentimentalist is he who would enjoy without incurring the immense debtorship for a thing done" (9.209).

Mulligan gives Stephen a hard time for ditching him and Haines at the bar, going on and on about how sick they were with thirst.

Stephen laughs.

Mulligan informs him that Synge is looking for him to murder him because he heard Stephen peed on his doorstep.

Stephen points the finger at Mulligan, and says, "That was your contribution to literature" (9.217). The two of them are in high spirits.

Stephen recalls Synge's rude manner when they would meet in Paris to discuss literature.

An attendant informs Lyster that someone (Bloom) wants to see files of the Kilkenny People. Lyster and the attendant go out to help him.

Buck Mulligan sees Bloom through the doorway. He teases Stephen that Bloom is gay, and suggests that Stephen be on the lookout. He says that he saw Bloom in the lobby looking up under the skirts of the statue of Aphrodite.

Eglinton now encourages Stephen, says he wants to hear more about Ann Hathaway.

Stephen notes that Shakespeare lived in London for twenty years, and that there is little doubt he had a bawdy time there. Stephen generally cites evidence and rumors to paint a picture of Shakespeare as a Don Juan figure. Stephen himself remembers a conversation with a prostitute in Paris.

Stephen then asks what they think that Ann Hathaway was doing tucked away in Stratford all those years.

Mulligan jumps in and asks Best who he thinks the male figure in the sonnets is.

Best cites the well-known theory, which Wilde himself supported, that W.H. is William Herbert, Lord of Pembroke, and that Shakespeare felt spurned by Herbert as well as his love-interest, Mistress Fitton.

Stephen thinks of the alleged pseudo-homosexual relationship between Shakespeare and the W.H. of The Sonnets, the "love that dare not speak its name" (9.251).

Eglinton asks if Mulligan is just speaking of an Englishman's love for his lord.

Stephen notes how preoccupied the ghost in Hamlet is with the infidelity and with his brother's stupidity, with whom his wife is now having an affair. Stephen thinks that Ann was "hot in the blood" (9.254).

Stephen tells Eglinton that the burden of proof lies with Eglinton and not Stephen. He asks why Shakespeare never mentioned Hathaway for thirty-four years after their marriage.

Eglinton asks if he is speaking of the will, and Stephen points out that "he left her his secondbest bed" (9.260). Eglinton contends the point, but Stephen argues that Shakespeare was a wealthy countrygentleman and that he could have left her his best bed.

Mr. Best clarifies that they know, at least, that there was a best bed and a secondbest. Mulligan quotes the Latin legal line for a separation, and they all smile.

Eglinton tries to remember other famous wills, and Stephen remembers the terms of Aristotle's will. Mr. Best is confused.

Mulligan quotes the belief that Shakespeare died while dead drunk. Mr. Best is still confused.

Mulligan tells them all what Dowden, a professor at Trinity, said when he asked him about the charges of pederasty (having sexual relations with other men or with children) brought against Shakespeare. The professor said they all lived very highly in those days.

Best says their sense of beauty is leading them astray.

Eglinton thinks that Freud's terms can explain the charges of pederasty. Stephen hopes that his artistic argument will not be wrested from him by psychoanalysts.

Stephen suggests other influences for Shakespeare's characters, both from his life and from histories that he read. In particular, he thinks that Shylock himself was based on Shakespeare.

Eglinton challenges Stephen to prove that Shakespeare was a Jew. The common belief is that he was a Roman Catholic.

Stephen cites the fact that the Germans tried to expropriate Shakespeare.

Mr. Best reminds them of Coleridge's phrase, that Shakespeare was "myriadminded" (9.283).

Stephen thinks of some lines of St. Thomas's, and begins a new line of argument. Mulligan cuts him off and bemoans the fact that he is bored and that the whole thing is dragging on.

Stephen (misquotes) St. Thomas by saying that he viewed incest as avarice (greed) of emotions. He compares this to the fact that Christians were bound by law not to lend people money with interest, but Jews were not. He thus suggests that inter-marriage among Jews is a way of withholding their own people from the desires of outsiders, another form of avarice (anti-Semitism) runs rampant.

Mr. Best thinks that they are handling Shakespeare quite roughly.

They all pun on the word "will."

Stephen suggests that Ann became very pious after the death of Shakespeare, perhaps due to remorse of conscience.

Eglinton agrees, but then remembers what Russell said. He doubts that Shakespeare's family experience is actually important to his plays. He thinks that Falstaff was Shakespeare's greatest creation.

Stephen remembers being summoned from Paris to his mother's deathbed. He remembers being calmed by the doctor, who did not know him.

Stephen argues, "A father is a necessary evil" (9.301). He says that John Shakespeare is not a very important figure, that fatherhood is a mystical estate. He says fatherhood is founded upon the void, that a mother's love may be the only true thing in life.

In his head, he argues with himself and wonders why he must press the point so.

Stephen thinks that there is a certain shame associated with fatherhood. He notes that for the son, "his growth is his father's decline, his youth his father's envy, his friend his father's enemy" (9.306).

He remembers the street in France where he first had this thought.

He tells them that hardly anything links a father and a son except "an instant of blind rut" (9.308). Stephen wonders if he might be a father, and how he would think if he were one.

Stephen argues that Shakespeare himself was his own father, that in renouncing his position as a son he "was and felt himself the father of all his race" (9.311).

Eglinton seems impressed, and Mulligan begins joking about the idea of a man giving birth.

Stephen then extends his theory to Shakespeare's family, and matches different incidents in his life with incidents in his plays.

Lyster returns, and the text briefly turns into a play dialogue.

Stephen thinks that Shakespeare's brothers Richard and Edmund are involved in the plays.

Eglinton wonders what one can conclude from names alone. Best kids that his name is Richard and wonders if Stephen will speak well of Richard. All laugh.

Mulligan begins reciting a poem he has made up, and Stephen notes how the villains in Shakespeare's plays bear the names of his brothers.

Best continues joshing him, and everyone laughs.

Stephen persists. He argues that Shakespeare has hidden his own name in his work, except for The Sonnets where it exists in overplus. He thinks of how young children try to read their names as a sign of destiny, and remembers a star that rose in the sky and outshone all the others when Shakespeare was eight. Some people in England thought it might signify the second coming of Christ.

The men look satisfied, and Stephen thinks he won't tell them that the star faded when Shakespeare was nine.

Silently, Stephen thinks of what he might see in the stars if he tried to look for signs of himself.

Lyster questions Stephen about this star that rose during Shakespeare's life. Stephen explains it briefly.

He thinks that Mulligan's boots are misshaping his feet and that he must get his own.

Eglinton is pleased with Stephen's interpretation of Shakespeare's name, and notes how odd his own name is. Stephen thinks upon the origins of his own name.

Mr. Best notices how the "brother motive" that Stephen suggests is also present in Irish myth. He wonders if there was misconduct with one of the brothers.

An attendant calls for Lyster, saying that Father Dineen needs help. Lyster again disappears.

Eglinton presses Stephen to expound his theory of Richard and Edmund, but Stephen is tired. He thinks, "I am tired of my voice, the voice of Esau. My kingdom for a drink" (9.360).

Stephen argues that for Shakespeare the theme of the false usurping and adulterous brother is the most persistent one in his work. As he wraps up, "he laughs to free his mind from his mind's bondage" (9.365).

Eglinton suggests a compromise. They will view Shakespeare as both the ghost and the prince. Stephen agrees, and rapidly begins to pull in other Shakespeare characters to argue the point.

Mulligan clucks at him jokingly.

Eglinton admires Iago, and recollects the line "After God Shakespeare has created most" (9.371).

Stephen wraps up in wild eloquence. He explains how hard it is to get away from oneself, saying, "Every life is many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love. But always meet ourselves" (9.372).

In closing, he concludes that every man is his own wife.

Mulligan begins crying Eureka. He runs and grabs paper and pen from Eglinton's desk and begins scribbling.

Best laughs, and Eglinton says that Stephen has gone all this way to give them the French triangle of man-wife-lover.

Eglinton asks if Stephen believes his own theory. Stephen says that he does not.

Best suggests that he write it out like a Platonic dialogue.

Eglinton tells him that he shouldn't expect to be paid if he doesn't believe his own theory.

Stephen thinks, "I believe, O Lord, help my unbelief" (9.386).

Stephen offers to let him publish the whole thing for a guinea (a small amount of money).

Mulligan gets up merrily and summons Stephen to leave with him and get a drink. Eglinton tells Mulligan that they will see him tonight at George Moore's.

As Stephen follows Mulligan out, he wonders what he has learned from the whole discussion. He thinks that he is following after Mulligan as Haines does. He sees the madman Farrell in the reading room as they exit.

Mulligan is half-singing and talking about the skill of those writing for the Abbey Theatre.

Stephen is still thinking about material for his Shakespeare argument, but reflects that it is now too late.

Mulligan sings some lines of Yeats, and notes what a mournful character Synge has been lately wearing only black. He chides Stephen for writing a negative review of Lady Gregory's work even though she was the one who recommended him to the paper. He asks him why he can't be more like Yeats and heap undue praise on her.

Mulligan announces that he has written a play called "Everyman His own Wife or A Honeymoon in the Hand (a national immorality in three orgasms)" (9.435). He reads off the characters and laughs.

Mulligan remembers a time Stephen was blacked out drunk in Camden Hall, lying in his own vomit. The young women had to lift their skirts to step over him.

While Stephen is still stewing the Shakespeare argument over in his head, Bloom passes out between them. Mulligan greets him. He kids Stephen that Bloom had turned a lustful eye on him.

Silently, Stephen thinks that it's his English education that has made Mulligan so homophobic.

As they follow Bloom out into Kildare Street, Stephen sees two plumes of smoke rising. He tells himself to stop striving away after his argument, and the plumes bring to mind the final lines of Shakespeare's Cymbeline: "'Laud we the gods and let our crooked smokes climb to their nostrils from our bless'd altars'" (9.457).

Stephen has something to prove in this chapter. In a way, this is hardest on the reader, because it means he has all of his genius going at full blast, and his argument can become quite involved and difficult to follow. Most immediately, he is trying to show off for the renowned Irish critic John Eglinton and the well-known mystical poet George William Russell (A.E.). Stephen refuses to align himself with either of the men. He wants no part of their role in the Irish Literary Revival, and does not think much of Russell's mystical approach to writing. At the very start of the chapter, he argues for the importance of Aristotle, who thought art should be grounded in the material world, against that of Plato, who thought that art needed to capture formless spiritual essences. Despite his defiance, however, Stephen very much wants to impress both of them. He is particularly hurt when they make no motion to invite him to George Moore's reading that evening, and when he discovers that Russell is not going to include him in his collection of young Irish poets.

But there's another figure that Stephen is struggling with in this chapter, one not actually present in the room. The figure is William Shakespeare. As Stephen elaborates his theory, we see that it is quite far from a traditional literary argument. It's wildly clever and often stated quite eloquently, but what becomes clear as the argument moves on is that Stephen is attempting to figure out his own artistic purpose through Shakespeare. Stephen argues for an art that can be grounded in everyday life (as Joyce did) by elaborating ways that Shakespeare pulled material from his family life for his plays.

Occasionally, we see Stephen's thoughts turn to his own experience even as he is discussing Shakespeare. For instance, when he is talking about what a raucous time Shakespeare must have had in London, he remembers his own conversation with a prostitute while he was in Paris. We here get a glimpse of the intensity of Stephen's literary ambition: he views himself as being on par with Shakespeare.

You'll notice that Stephen's argument becomes particularly pointed when he argues for the irrelevance of fathers. Stephen says, "a father is a necessary evil," and argues that "fatherhood, in the sense of conscious begetting, is unknown to man. It is a mystical estate, an apostolic succession, from only begetter to only begotten" (9.301). On the simplest level, what he is saying is that the process of childbirth is almost completely relegated to women. If a mother doubts that she is going to create a new human life, then she is reminded of it day in and day out for nine months, which culminates in the pain of childbirth. For men, however, the process of creating a new human life is tied to a relatively brief sexual act. Beyond that, they must struggle to imagine what it means to create another human being. This is the reason that fatherhood "is unknown to man." The theme will come up again in "Oxen of the Sun" when we see the process of literary creation compared to childbirth. In short, women give birth, and men, to compensate, write books.

It's not just the comparison of literary creation to childbirth that has Stephen so impassioned. We have seen evidence in the first eight episodes that Stephen feels estranged from his father, Simon, who is more of a drunkard and a town jokester than he is a father. There is little to indicate that Stephen's father takes much interest in his son or understands his ambitions. The lack of a father figure is one of the major reasons that Stephen seems so isolated in the novel, and it will become increasingly apparent as the novel develops that Bloom can become a sort of surrogate father figure for Stephen. For the moment, though, that surrogate father is busy looking up the skirts of Greek statues in the Library lobby.

Now, in Book 12 of The Odyssey, Odysseus and his men must find a passage between Scylla and Charybdis. Scylla is a six-headed monster that lives on a sharp mountain peak, and Charybdis is a giant whirlpool. Circe has already told Odysseus that to pass through he must steer closer to the rock of Scylla than to the yawning mouth of Charybdis. The correlation to the two figures is clearest in the opening of Stephen's literary argument. The way that Aristotle grounds art in material reality is comparable to the hard rock of Scylla, whereas the way that Plato pushes for art as a revelation of the ideal, of formless spiritual essences, is more like the whirlpool. Both Eglinton and Russell are more sympathetic to Plato whereas Stephen stays closer to Scylla (Aristotle).

In The Odyssey, Odysseus forgets Circe's advice and tries to engage Scylla in combat. As we see the details of Stephen's biographical argument become more and more complex, we might draw another comparison. Stephen briefly forgets to steer his course and instead gets too wrapped up in his own argument. Ultimately, it is Eglinton who has to remind him that the truth lies midway between the two different stances.

Stephen's ability to get too involved in his own argument becomes especially apparent toward the end of the chapter. Even as he and Mulligan are walking away, he is still summoning details to support his point. He has to silently coax himself to stop thinking about Shakespeare. In "Proteus" Stephen's intellectual ramblings seem very free and loose. Here, we get a sense of how one's own mind can seem like a prison when one is as intelligent as Stephen is. In short, he can't stop thinking. We see this when Stephen wraps up his argument: "he laughed to free his mind from his mind's bondage" (9.365). Laughter, for Stephen, is a way of calming down his mind, a way of not taking himself too seriously.

Stephen's inability to stop intellectualizing again becomes apparent when Eglinton asks him if he believes his own theory. He promptly says that he does not. Why not? Well, to believe in something is not the same as to know something. Belief requires that, at some point, one suspend one's questioning and intellectualizing and just accept that which one feels to be true. At this point in the novel, Stephen is incapable of controlling his thoughts. As much as he wants to, he doesn't yet believe in anything.