Penelope

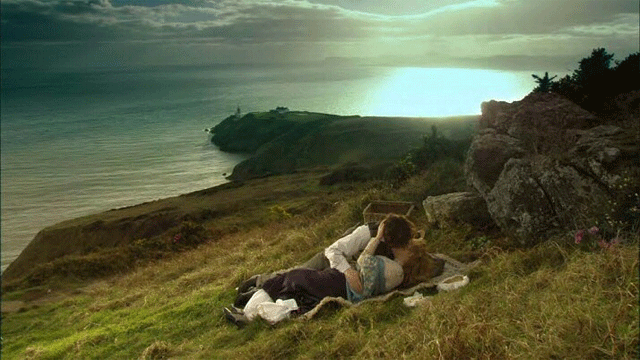

we were lying among the rhododendrons on Howth head . . .

It is sometime in the middle of the night, in the bed of Molly and Leopold Bloom. In the Linati schema, Joyce listed the time with the infinity symbol to indicate that Molly does not live her life by the clock. The entire episode is done in eight long sentences (the numeral 8 turned sideways is the infinity symbol), laying out Molly's wandering thoughts as she lies awake in bed beside Bloom. Because there are no paragraph breaks, this refers to the page numbers of the standard Ulysses edition (Vintage International, corrected and reset in 1961).

Molly is shocked that Bloom has asked her to make him breakfast in bed the next day.

She thinks begrudgingly of how, when they were living in the City Arms hotel, Bloom would look so carefully after that old miser Mrs. Riordan. Riordan never gave them any recompense for their troubles.

Old Mrs. Riordan was also down on low-neck shirts and swimsuits, and Molly thinks "I suppose she was pious because no man would look at her twice" (18.738).

Mrs. Riordan would always jabber on about things of no importance, and her dog would always stick its nose up Molly's petticoats.

Molly reconsiders Bloom and thinks she actually likes his kindness to the less fortunate.

She thinks that if Bloom ever gets really sick it's better that he goes into a hospital; men always want a woman looking after them as soon as they come down with anything.

Molly remembers one time Bloom sprained his ankle at a party and a woman named Miss Stack brought him flowers; she recalls her "old maids voice trying to imagine he was dying on account of her" (18.738).

Molly knows about Bloom's pornographic picture of a nun in the desk drawer and she thinks that he must have been cheating on her at one time or another.

There was one time early on when Bloom flirted with a girl at the traveling show Pooles Myriorama not long after they were married; he looked all shy after she caught him at it.

Molly knows he has some sort of illicit correspondence going on because she came in to tell him about Dignam's death and he tried to hide a letter that he was writing. She thinks that whomever the woman is (i.e., Martha Clifford) she's just trying to get money out of him.

She thinks "the usual kissing my bottom was to hide it not that I care two straws who he does it with or knew before" (18.739). In other words, she intuits that he may have had an orgasm earlier that day (which he did).

Remembering their servant Mary Driscoll, Molly suspects Bloom was having some sort of fling with her as well. He tried to suggest that Mary eat at the Christmas table with them and Molly wouldn't have it. She accused Mary of stealing oysters, and Bloom tried to stick up for the servant, but she got the can.

Molly remembers Boylan squeezing her hand one night in the Tolka when she was with Bloom.

She thinks that she could easily seduce a young boy for herself and thinks of how young boys are so timid and curious about sexual matters asking one question after another – would you do it with this person or that person or that person?

She thinks that there's no way Bloom can turn her into a prostitute this far into their marriage. Her thoughts on sex with Bloom: "pretending to like it till he comes and then finish it off myself anyway" (18.740).

After the first time sex is just an ordinary thing for most people, but for Molly "there's nothing like a kiss long and hot down to your soul almost paralyses you" (18.740-741).

She remembers going to confession and how much she disliked telling the Father about all of her exploits in detail. She wouldn't mind having sex with a priest.

She gets back to thinking about Boylan.

She wonders "was he satisfied with me one thing I didn't like his slapping me behind going away so familiarly in the hall though I laughed Im not a horse or an ass am I" (18.741).

She wonders where Boylan got the flower he had and wonders if he is awake thinking of her. When the thunderbolt (the one that scared Stephen in the maternity hospital) sounded while they lay in bed together, it shocked Molly awake and made her wonder if they were being judged.

Bloom never goes to Church and doesn't believe in God, saying there's only grey matter inside, but Molly thinks that he doesn't believe in a soul just because he doesn't know what it is to have one.

She remembers that Boylan had an orgasm three or four different times. She thinks that he has the biggest penis of any guy she's ever slept with (though Bloom has more sperm).

Molly believes it is unfair that women are made with this great big hole in them so that they can be rammed as if by a stallion. Molly thinks about the pain of pregnancy and how Mina Purefoy's husband fills her up with kids every year.

Molly remembers when she first came across Leopold and how he had Josie Powell on his arm. They got in a row about politics and he made Molly cry, but she didn't mind so much because she could tell he was already head over heels for her.

On the bright side, Bloom does know a whole lot of things, especially about the human body.

She remembers how jealous he was at first and how he made her a present of Lord Byron's poems.

Molly gets to thinking about Josie Powell, and says that she would have just gone straight up to her and asked if she was in love with Bloom. She remembers the first time Bloom told her that he was in love with her and how much work it took to get it out of him.

Josie used to hang around the two of them, but once things got more serious she left them alone. Molly thinks that Bloom was actually quite attractive at the time, always making an effort to look like Lord Byron.

She imagines how hard it must be for Josie to live with that madman Denis, and how she's heard that he climbs into bed with his boots still muddy. At least Bloom takes his boots off.

Molly thinks, "Id rather die 20 times over than marry another of their sex of course hed never find another woman like me to put up with him the way I do" (18.744).

She wonders why men ask women to marry them in the first place and remembers the famous case of Mrs. Maybrick who was convicted of poisoning her husband with arsenic, supposedly because she was actually in love with another man.

Molly begins to think of Boylan at length. She remembers how early on he was obsessed with the shape of her feet.

Initially, Bloom was very infatuated with her; when she lost a pair of gloves he bought her he wanted her to put an ad in the paper.

Molly remembers a time Bartell D'Arcy began kissing her and then became embarrassed.

Bloom used to be obsessed with her underwear. He'd beg her for a cut of it, and couldn't keep his eyes off girls bicycling in the streets who get their skirts blown up by the wind.

She thinks of how men can do whatever they want but as soon as a woman wants to do something on her own, men are full of questions and go skulking after her.

She remembers a time Bloom touched her underwear in the street and how incredibly horny he was, and she had to control him from doing anything out in the open.

Later, he wrote her an erotic letter and then asked if he offended her.

Molly remembers other lovers, and hopes that Boylan will be on schedule next week noting that she always has such a hard time keeping track of the hour.

Molly thinks of Bloom going to Ennis for his father's anniversary. She imagines that if Boylan comes (for a singing tour), it will just be incredibly awkward because he'll be jealous of what goes on with Bloom and vice versa.

She thinks about how pigheaded Bloom is and remembers a time that he refused to get out of a train carriage until he had finished his soup, and had to use his knife to get them out because the carriage closed.

Another time, Bloom tipped a guard on the way to Howth to give them some privacy. She thinks of the Dublin concert scene, and how Bloom used to work to try to promote her career.

Molly remembers a young lieutenant Gardner who kissed her goodbye at the canal lock and talked about her Irish beauty.

She thinks of how much she likes watching military regiments in review and imagines a trip to Belfast with Boylan, where they could shop and be undisturbed.

She thinks "he has plenty of money and hes not a marrying man so somebody better get it out of him" (18.749).

Boylan is very heavy, and Molly wonders why they don't just have sex from behind all the time like Mrs. Mastiansky told her she does with her husband.

She remembers how Blazes was in a fury when he first got to the house about losing money on Sceptre, and how angry he was that Throwaway came from behind and won the Gold Cup race.

She thinks of the different clothes she wears for Boylan including a corset, and gets to thinking that she could probably lose some weight.

Bloom was supposed to get her facial cream today, but she assumes that he forgot. She thinks about going clothes shopping as she would like to dress more stylishly for Boylan. Bloom thinks that he has great taste in women's dress.

The books Bloom has been getting for her are too fantastic; she doesn't like them.

Molly thinks Bloom "ought to chuck that Freeman with the paltry few shillings he knocks out of it and go into an office or something where hed get regular pay" (18.752).

She had gone in to see Mr. Cuffes after Bloom was fired, trying to help plead for his job back. Cuffes stared down hard at her chest and then showed her out, telling her how extremely sorry he was.

Molly thinks of how beautiful her breasts are and how ugly male genitalia are in comparison (though men are always trying to show you what they've got). It makes sense to her that a woman's breasts are revealed in Greek statues whereas male genitalia are hidden under a cabbage leaf.

She remembers that after Bloom lost his job at Helys, he suggested that she could pose nude to make some money.

She thinks of the nymph picture they have hanging over their bed (remember the nymph character in "Circe" – this is where she comes from), and how Bloom is so bad at explaining complicated things (like metempsychosis this morning).

When Molly was pregnant with Milly, Bloom used to suck on her breasts and say that he wanted to put the milk right into his tea.

She thinks of the ridiculous things her husband says; she would like to make a book of Poldy's sayings.

Molly thinks back to her orgasm with Boylan this afternoon and how he had her going for about five minutes. She wishes she had someone to go with right now.

She thinks, "I noticed the contrast he does it and doesn't talk I gave my eyes that look with my hair a bit loose from the tumbling and my tongue between my lips up to him the savage brute Thursday Friday one Saturday two Sunday three O Lord I cant wait till Monday" (18.754).

There is a powerful train whistle, which gets Molly to thinking of how careless Bloom has become just leaving things around the house.

The rain earlier makes her think of her youth in Gibraltar and the incredible heat there. She remembers her good friend, Hester Stanhope, and the man who eventually became her husband – "Wogger" (18.755). They exchanged letters after she left and all the while Molly wished she were back in Gibraltar.

Molly remembers going to a bullfight in Gibraltar, and she recalls a number of different books that she read in her boredom after Hester left – mainly romances and detective stories.

She recalls the military gun salute in Gibraltar and the time that Ulysses S. Grant visited the city on his world tour, to great acclaim.

There is a medical student in Holles Street that Molly was making eyes with. She thinks how when you try to flirt with men they are incredibly oblivious – you might as well write it on a poster and pin it up for them.

Molly is irritated that Milly wrote her a card whereas she wrote Bloom a whole letter.

She remembers a friend, Mrs. Dwenn, who wrote her a letter out of the blue and gave her a bunch of news.

Dwenn referenced a funeral in her letter, and Molly thinks that she can't stand people who go around telling poor stories since everyone has their own troubles anyway.

She hopes Boylan will write her a letter in the future, but doubts it.

She thinks, "as for being a woman as soon as youre old they might as well throw you out in the bottom of the ash pit" (18.759).

Molly remembers her first love letter ever – from Lieutenant Mulvey, brought in by the family servant, Mrs. Rubio. She thinks of Mrs. Rubio and how she could never get over the Atlantic Fleet passing through Gibraltar.

She remembers being thrilled by the letter and astonished that he would make an appointment letter to see her.

Mulvey was the first boy to kiss her, down under the Moorish wall, putting his tongue in her mouth and she sliding her knee up between his.

She remembers how he crushed all the flowers he'd brought for her on her chest, and how she claimed she was going to marry a Spanish nobleman named Don Miguel. She thinks, "theres many a true word spoken in jest" (18.759).

Later, they lay together in a firtree cove and he massaged her breasts through her shirt while they watched the ships go through the strait of Gibraltar.

She remembers how he wanted to have sex with her right from the get go, but she was too afraid, though she did masturbate him and show him the inside of her petticoats.

She wonders what's happened to Mulvey now, and thinks that his wife has no idea what she did with him before they even met.

Molly considers the fact that she never imagined her name would be Bloom. She used to try writing it out on postcards, and Josie Powell used to tease her about it after they were married. But she doesn't like the name Mulvey either.

Men's constant traveling seems silly to Molly; why don't they just stay in one place?

She thinks about how stale Dublin women are, and how she knew more about life at fifteen than any of them do now.

Another train whistle gets her thinking of Love's Old Sweet Song, and she remembers the way Gardner used to flirt with her.

She thinks of her looks and imagines if she had married a real man like Boylan she could have been a prima donna (modern day diva, that is). Except she married Bloom.

She has to fart and shifts around on the bed so as not to wake Bloom. She wishes he'd sleep off in his own bed because his feet are so cold. The fart mingles with the sound of another train whistle.

Molly thinks what a relief the fart was. She thinks that she doesn't like being alone at night now and remembers being a little girl in Gibraltar and being afraid of the dark.

She hopes that the medical students (i.e., Stephen) won't trick Bloom into thinking that he's young again. What on earth do they talk about until 4am? At least Bloom didn't wake her.

Molly remembers that Bloom asked for breakfast in bed the next morning and imagines him sitting there eating like a ridiculous king. What food should she buy tomorrow? Maybe cod.

Bloom once claimed that he knew how to row a boat, and Molly remembers the two of them out there with the water running into the boat and him trying to instruct her though he clearly had no idea what was going on. She thinks that she would have liked to pull down his pants and flogged him right in front of everyone.

She thinks again that she doesn't like being alone in the house at night, and remembers how Bloom promised her a bunch of different places they could go for their honeymoon (Venice or lake Como), but instead they are always just stuck right here in Dublin.

Molly remembers a time that there was a noise downstairs and Bloom got up to see who it was. He was white as a sheet and was making as much noise as he could for the burglar's benefit.

It was Bloom's idea to send Milly to photography school in Mullingar, and Molly suspects that he did it because he saw her affair with Boylan coming.

She begins to think of Milly and how she fawns over her father, though she thinks that Milly would come to her if anything was actually wrong.

She remembers sewing a button on Milly's jacket and smelling cigarette smoke on her, and thinks it's just as well she went to Mullingar because she was getting to that age where she would test all sorts of boundaries.

Molly thinks that Milly is wild and beautiful like she was at that age.

She thinks of how much she hates it when men try to tap your behind in public and she remembers a man in Trilby who did it to her a couple of times.

Molly remembers a boy that Milly was bringing over for meals regularly and how she wandered if it was true love. She thinks that a dedicated man who believes in love is tough to find nowadays.

Molly suspects that Milly knows how pretty she is.

She thinks that now they won't be able to get a new servant after the business with Mary Driscoll, and remembers hearing of Stephen winning a bunch of academic prizes.

Molly remembers Bloom climbing over the railing to get to the lower door, and wonders that he didn't rip a hole in his trousers. She wonders what the neighbors would have thought if they saw him.

A wife never gets any peace from her husband, and men are so hypocritical about adultery.

Molly feels her period starting, coming on heavier and heavier. She's quite irritated, and wonders briefly if Boylan made her pregnant (he didn't).

She thinks how men "always want to see a stain on the bed to know youre a virgin" (18.769).

The bed was making too much noise when she and Boylan were having sex and she imagines that the neighbors might have heard. They had to put a quilt down on the floor after that.

As she hobbles over to the chamberpot to let the blood run out of her, she thinks about her afternoon with Boylan and hopes her breath smelt alright after she took him in her mouth.

Molly is in the bathroom, and thinks back to a very unpleasant visit to the gynecologist where he kept referring to her "vagina."

She thinks of Bloom's early letters to her, and how they were crazy for each other at first, one night they just stood staring at each for ten minutes from across a terrace.

She remembers how people said Bloom would run for parliament and how he would go on about the home rule question, and she thinks that she never should have listened to any of his blather. As she says, "he wont let you enjoy anything naturally" (18.771).

She thinks of how he kneels when he pees and of all the other totally bizarre habits that her husband keeps up, like sleeping with his head at the base of the bed. She imagines that if he jolted in the night he could kick all of her teeth out.

Molly worries that Bloom spent money on a woman today, and thinks it's just like him to have to pay for it.

Remembering where she got her marriage bed, Molly notes it's a secret Bloom isn't in on.

She thinks of all the different places they had to move throughout their sixteen years of marriage on account of Bloom's constantly losing his various jobs.

The bells of George's church toll, and Molly can't believe how late Bloom came home. She thinks that tomorrow she'll rifle through his pockets and find a condom in one of them. According to Molly, men never can hide all their dirtiness.

Molly still can't get over the fact that he asked for breakfast in bed, and thinks that perhaps he lost interest in her one night after she wouldn't let him lick her in Holles Street.

She thinks that Bloom is no good when it comes to sexual matters and wonders if he is sleeping with Josie Breen. No. He wouldn't have courage to sleep with a married woman anyway.

Molly saw about Paddy Dignam's funeral in the paper. She thinks of all the men that were there and thinks, "they call that friendship killing and then burying one another" (18.773). (Note that Dignam died from drinking.)

Molly won't let Bloom in their clutches. She knows all too well that they condescend to him and make fun of him behind his back.

Molly's thoughts move to singing and she thinks of how Simon Dedalus used to show up with Ben Dollard and sing while he was still half drunk.

She wonders what Stephen was doing with Bloom, and remembers that Bloom told her Stephen was a professor of Italian and that he showed her Molly's photo. Molly worries she didn't look very good in the photo.

She remembers seeing Stephen when he was much younger and she was in mourning for Rudy.

She thinks of a prediction made on one of her tarot cards this morning and wonders whether or not it has something to do with Stephen.

She compares his age to Milly's, and thinks that he must not be stuck-up like the other university students if he stays up half the night with Bloom.

Molly imagines that Stephen isn't too young for her and that one day he'll probably be a great poet and write verses about some woman or another.

She wants to kiss Stephen all over his body. The two of them could become a famous couple in Dublin: "I can teach him the other part Ill make him feel all over him till he half faints under me then hell write about me lover and mistress publicly too with our 2 photographs in all the papers when he becomes famous O but then what am I going to do about him though" (18.776).

In contrast to Stephen, Boylan has absolutely no manners; he is "the ignoramus that doesn't know poetry from cabbage" (18.776).

She thinks that it was her bust that first attracted him to her.

Molly finds it bizarre how Bloom acts so coldly to her, never kissing or embracing her except kissing her on the bottom when he's asleep at the wrong end of her.

It's completely unnatural for a man to kiss a woman's bottom, and if Bloom was any other man Molly'd throw her hat at him.

She fantasizes about grabbing a sailor off the docks and having sex with him, but she worries that sailors have all sorts of diseases.

Bloom snores and she wishes he'd move his big, dull body away from her. She thinks of making him breakfast the next morning and how you do a nice thing for a man and he doesn't do anything except treat you like dirt.

The world would be a better place if it were governed by women; women aren't always out getting drunk and starting fights and so on.

Molly thinks that the problem is that men don't know what it's like to be a mother. She thinks that Stephen is so rowdy, aimlessly carousing the city at night, because he's astray after having lost May.

May's death makes her think of Rudy and she immediately feels guilty for it. She thinks that after he died she knew she'd never have another child.

Maybe Stephen is right and women really are just a dreadful lot.

Stephen's last name, "Dedalus," strikes Molly as queer and it makes her think of a bunch of other bizarre names from Gibraltar.

She wonders why he didn't stay the night and thinks that he's just as shy as a young boy. She imagines that if he gives her Italian lessons she can teach him Spanish so he won't think that she's ignorant.

Molly (as Bloom did) considers all the benefits of Stephen staying with them for a long period of time. He could conduct his studies in his room with peace and quiet and if Bloom's making breakfast for Molly, he could just as easily make another for Stephen.

Molly thinks that she'll go to the market the next day and get a big juicy pear.

Yes, maybe she'll wake up and walk around and sing opera and let Bloom see her underwear so that he gets a hard-on. Then she'll tell him all about the affair with Boylan in explicit detail and show him Boylan's semen stain on the sheet.

She thinks, "Its all his own fault if I am an adulteress" (18.780). If he tries to kiss her rump again she'll pull down the back of her trousers and stick it right in his face.

There are a number of different ways to pull the truth out of Bloom about whether or not he saw a woman today.

Looking at the time, Molly can't believe what an ungodly hour it is and imagines that people are probably waking up in China right now.

She plans on putting flowers all around the house in case Stephen comes back, and this makes her remember living in Gibraltar as a young girl.

(Just a note: please, please do yourself a favor and read the last two pages of Ulysses, regardless of how you've done with the rest of the book.)

She thinks of all the men sitting around debating about whether or not there's a God, and she thinks that they don't actually know any better than she does. She wonders why they don't go and create something, and thinks that they may as well try to stop the sun from rising as speculate on abstract philosophy.

This makes her think of the day that Bloom proposed to her on Howth's Head, and told her that the sun shines for her. He called her a flower of the mountain; "that was one true thing he said in his life" (18.782).

She didn't answer him at first, just looked out over the sea and thought of her childhood in Gibraltar and all the other lovers she has had.

And then she thinks, "well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes" (18.783).

First, let's do our best to settle a long-held debate over "Penelope:" Joyce is not a woman. In the years after Ulysses was published, a lot of people observed Molly's sexual frankness and thought that Joyce had just created Bloom's wife as a prostitute. With time, they came to appreciate just how nuanced Molly's thoughts were and they sort of stepped back and revised their earlier opinions. But with the growth of feminist criticism in the 1970's, the debate was taken up again. The problem, the critics pointed out, is that this is known as a big feminist moment in literature: look at James Joyce open up the female perspective. The critics said, "That's not the female perspective! If you men think that all we think about at night is sex and how we're seen by the men in our lives, then you've got another think coming!" Point taken.

Joyce is not a woman. He doesn't know how women think, but he's trying. It's well known that Molly was modeled on Joyce's wife Nora Barnacle, who he was married to all his life and with whom he was passionately in love. Nora was from the west of Ireland, and in contrast to Joyce's historic erudition, she was a very down-to-earth woman who didn't even think Joyce was much of a writer. As she put it, he should have stuck to music.

Now at one point there was a rumor going around Dublin that Nora had slept with an acquaintance of Joyce's early on in their relationship. It drove Joyce nearly mad with jealousy. More likely than not, it was nothing but a rumor, but for Joyce it became an incredible neurosis. For all of his genius, one simple thing he couldn't imagine was having the person you love most sleep with someone else. In his 1909 letters to his wife, he is at first harsh and accusatory, but gradually becomes more honest and reveals just how vulnerable and helpless he feels.

So one way to think of the end of this book is that Joyce is making an effort to imagine his wife's point of view in the worst of all possible worlds (the one where she actually is having an affair). These last few chapters – where Bloom resigns himself to Molly's affair – could not have been easy for Joyce to write. It's as if he is taking his jealousy and turning it inside out, using it as a weapon against itself, as if he's using his jealousy in order to imagine how a woman could cheat on her husband and still love him. Now whether or not he succeeds in blowing open a female perspective is, we admit, a matter of debate. But it's important to note that this is an honest try, and that the effort probably says as much about the male point of view (or attempts to overcome the male point of view) as it does about the female.

That said, this episode is spicy. Molly really is extremely frank about sex. She compares the size of Boylan's penis to Bloom's and talks about her orgasm in great detail. If you think that's pretty straightforward sex talk in the 21st century just take a second to imagine how it would have come across in extremely Christian Dublin almost a hundred years ago.

But Joyce has an aim here. If you take a look at the 1909 letters, you'll see that in the blink of an eye Joyce will go from talking about Nora as if she were the Virgin Mary to telling her in graphic detail what he wants to do to her in bed. What he is trying to do is to explode a common preconception about what women have to be. Part of the typical feminist critique of masculine culture is that it is founded on the division of "woman/ mother/ prostitute" (Froula, Modernism's Body, 88). Meaning that the only way women could attain respectable social status was by marrying a man or by being pure. For men, by contrast, one could grow to old age as a bachelor who pops into the brothel on a regular basis and still expect to function in polite society. Joyce is here trying to lasso this prejudice against women, to reveal Molly as a virgin (in the sense that Bloom worships her as if she were a goddess), a mother, and a "prostitute." As with Bloom, you can't come to an easy judgment about Molly. You have to accept all of her, good and bad, attractive and ugly, saintly and debased.

We'll take a second to note that the above could probably be boiled down into one of the take-home messages of Ulysses: "Don't be ashamed of your body or what you do with it. It's natural."

We've noted that Joyce at least tries to open up the female perspective. Remember that Homer never did. In The Odyssey, Penelope has told the eager suitors that she will choose one of them after she finishes weaving a shawl for Laertes, Odysseus's father. Except that she has just been sitting up in her room weaving and then unweaving the shawl waiting (she assumes in vain) for Odysseus. When her nurse, Euryclea, tells her that Odysseus has returned, Penelope does not believe her and thinks it is a god in disguise. She isn't convinced until Odysseus reveals his knowledge of the secret construction and immovability of their marriage bed (which only the two of them know about). They move into bed together and tell stories to each other. Odysseus gets up the next morning with an aim to pacify the island.

Now as in "Ithaca," this is one of those episodes that is more notable for its contrasts to The Odyssey than it is for its correlations. Here, Bloom doesn't exactly return home triumphant (or it wouldn't seem that way at first). Molly has slept with her false suitor and is reflecting back on it with pleasure. Plus the whole thing is from Molly's (i.e., Penelope's) point of view. Penelope is the missing perspective from The Odyssey: how does it feel to wait at home for your husband for seven years with no idea about whether or not he's going to return?

In Ulysses, as we read through Molly's bedtime thoughts we are forced to constantly revise our earlier conceptions of her. Up until the final episode, we've mainly heard other men gossip about her beauty and her promiscuity. Though Bloom thinks of her fondly, we get the sense that she is being incredibly cruel to her poor husband. Here, we learn that Molly suspects Bloom has been carrying on a number of little affairs and liaisons, and that he has not slept with her in over ten years. We add to that the fact that Boylan is her first actual affair in all of this time and that Bloom often acts cold and affectionless toward her. Given her own guilt over the death of their son Rudy, Bloom has not been the most ideal and sympathetic husband imaginable. By the end of the episode, we can begin to see things from her point of view: "its all his own fault if I am an adulteress" (18.780).

That's not to say that this is the right way of seeing things, that everything we've read so far has been incorrect. But Ulysses forces us to imagine a wide variety of points of view, to make us realize that any given event can only be understood when looked at in a variety of ways. As readers, we've got our critical light bulbs turned on and we're struggling to figure out what's correct, to come to one coherent judgment on the events. Joyce is determined to frustrate us, to make us realize that we've only seen one day in the life of the Bloom's. Who can judge people after only one day of knowing them?

In the last few pages of the book, Molly's thoughts turn to her husband and the time that he proposed to her on Howth's Head. This is often read as a small triumph for Bloom. Despite the fact that Molly is having an affair, her affections are ultimately still for her husband. The way we read this, the triumph is not just a small one for Bloom – it is a triumph of life over death, of affirmation over negation, of language over silence.

The prose in the last few pages of Ulysses is breathtakingly beautiful. Throughout Bloom's day, we've been forced to see all the banal unattractive parts of life: boredom, hunger, despair, the need to go to the bathroom, broken trust, small-mindedness, unrealizable dreams, apathy, our own insignificance. Joyce gives us a lot of very good reasons to think that life is a pretty tiny and horrible thing. Of course, we read this and we think that our life isn't going to be like Bloom's. I mean, he's one pathetic guy, our life will be infinitely better than Bloom's. But, truth be told, we have no way of knowing what our life is going to be. It's quite possible that one day we'll find ourselves in Bloom's shoes, in a marriage based more in fondness than in romantic love, in a place where most of our dreams are stretched out behind us rather than laid out in front of us. And for all that, Joyce is telling us: Do not despair. He's telling us to say yes to life, to swallow it whole, to find happiness wherever we can.

In the words of Molly Bloom, "I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes" (18.783).